The following essay was previewed in the class that Joshua Mohr taught for LitReactor, Plotlines: Crafting Powerful Story Progressions That Stay True To Character. Click that link to be notified should we offer an encore of this class.

In the reviews of my first two novels, the issue of the unreliable narrator has been mentioned often. Whether this is meant as criticism, compliment, or some tangle of the two, the following problem remains whenever this point is raised: I don’t believe in the unreliable narrator.

In fact, I’ll take it to the extreme and say that I don’t think there’s such a thing as a reliable narrator. The sculpted set of facts that a protagonist doles to a reader is in essence propaganda, revisionist history (assuming we’re in the past tense). Why are certain moments from a narrator’s suggested life included and others not? Think of all the omissions, the disasters and celebrations and banal meanderings not even touched upon in a narrative. Then ponder the moments a protagonist does zero in on and allow the reader to witness via scene or exposition. These are tactically included details; there’s a motive behind every disclosure. The question is who’s manufacturing these confessions.

The author? The narrator? Who’s in charge of reliably supplying the unreliable?

When I teach characterization, I always emphasize that authors should employ “useful schizophrenia.” It’s a fiction writer’s job to construct a heart, mind, and soul sovereign, idiosyncratic. If our characters are to be convincing body-doubles for real people, they must walk and talk and feel a range of emotion; they must giggle and have allergies and chew with their mouths open and grieve and play the harmonica (or whatever your particular story has them doing). The point is that they occupy an ecosystem in such a way that a reader recognizes the authenticity of life experience, even in a life that only exists on the page.

Of course, this idea of “useful schizophrenia” is an artifice, a dupe, a way for writers to dole more autonomy to the players. For if certain attitudes, biases, and crimes are assigned to the protagonists—rather than the writer—there’s a liberty to let the characters characterize themselves: they can stalk their habitats behaving however it is that they behave. The author is pardoned from the antics and can simply watch, channel, and document as the action unfurls.

This is the nascent stage of a character standing on her feet for the first time without the writer’s assistance. Yes, the author is always there, but the “useful schizophrenia” allocates thoughts, actions, and motives to the protagonist, letting them buoy the story. It’s a shift of emphasis in which Dr. Frankenstein sees the monster’s eyes open and turns it loose to live.

Once, the character begins to fend for herself, this is where unreliability becomes such a useful tool. Because, let’s face it, humans are ridiculous beasts when it comes to our own thoughts, actions, and motives (I once tried to convince myself that a DUI was a step in the right direction). These delusions and rationalizations are at the core of compelling narrative, or what I’m going to categorize as Narrative Stockholm Syndrome (NSS) going forward.

I’m going to keep my argument to the 1st person, or the “I” voice (though this is a cogent argument for other points of view, as well). According to the OED, an unreliable narrator is someone whose “account of events appears to be faulty, misleadingly biased, or otherwise distorted.”

Let’s look at these juicy adjectives—“faulty”, “biased”, “distorted.” The writer in me sees these and immediately smiles. There’s freedom in their implied liabilities; there’s the possibility to forge a protagonist who has a nuanced vantage point, one with her own faulty, biased, and distorted consciousness.

Each of our minds is these things—every human has a thought process that tumbles with varying levels of haze (faulty), sometimes intentional and others unintentional. We also have varying levels of narcissism coating our days (bias). And of course, our memories are flexible, contradictory, often trussed up contortions that bear little resemblance to other people’s renditions of the same set of “facts” (distortions in interpretation).

There are facts in the world. 2 + 2 = 4. There’s a force called gravity. If my heart stops beating I’ll die. But in terms of narrative construction, for writers looking to bring their characters to life on the page, the idea of NSS can be a powerful weapon to have in our arsenal.

Here’s a very elementary and probably incorrect synopsis of Stockholm Syndrome: It’s a phenomenon that can occur when a hostage begins to feel for her captive. She understands their motives—why they’re doing what they’re doing—even if it’s malicious, violent, etc. Maybe she even defends them after the fact.

How does Stockholm Syndrome translate to narrative construction?

Well, one pleasure of reading is being imbedded in the main character’s thought process, ensconced in a different worldview. When a reader sees life through a new lens, the character’s consciousness, she is in a place she’s never been before. Even in realist modes of storytelling, the protagonist’s psyche is a NEW WORLD. This reminds me of the John Gardner writing exercise to describe a river from the point of view of somebody who’s just fallen in love, and then render the same setting from the perspective of one who has committed a murder. Are they seeing the same place?

Literally, the answer is yes. But when we think about how the contextual details of their situations colors the milieu, they are witnessing very different places. For a lover, the river might seem ripe with life, the water a sign of hope, cleansing, etc. Yet the murderer, perhaps racked with guilt and denial and self-hatred, doesn’t see this optimism in the scene’s setting; no, rather than seeing possibility, she sees nature’s cruelty, the water crashing the rocks, slowly eroding them, gnats swarming, overcrowding, a nearby tree leers like an accuser.

Here’s the heart of NSS: when a reader is thrust into a consciousness, camaraderie develops between the protagonist and the reader (much like captive and captor). Assuming that the author has done her job right and constructed a convincing logic system and thought process, the “friendship” stems from the reader being privy to the mechanisms of decision making. They see how/why our characters do what they do, and empathy develops, even if these characters are behaving badly. We can think of this as the kiss between psychological realism and motive, and if we take the time to dote on this prospect, it will involve our readers more intimately with the characters, and thus, up their affinity with the story as a whole.

When I build characters’ psychologies/decision making mechanisms, I always imagine my readers to be leaves floating on a stream. In this example, the stream is the character’s consciousness, the logic system. The reader, while captive in this foreign landscape, just floats along, observing, witnessing, and after awhile, understanding how a character is hard-wired, even if that character is vastly different than the reader herself.

Maybe it’s in this space that literature can perform its most important function: maybe it can teach empathy. Maybe looking through the perspective of someone who challenges or belies our moral coding can help open our minds to the experiences of others.

It’s my hope that the phrase “unreliable narrator” comes to be categorized as redundant. Of course, our narrators aren’t reliable. Who would want them to be? They’re telling their remix of history, their rationalizations. We’re the nosy neighbors peeking in and gobbling up the “facts,” even when we know the facts are contorted, slanted.

Besides, where would the fun be if things weren’t all gummed up, biased, and wonky? That’s the humanness, the “us.” We recognize ourselves in well rendered characters because they have a point of view, a vantage point, a voice, a heart, strengths and weaknesses. That’s not only what makes them real people on the page, it’s what brings us to life as well.

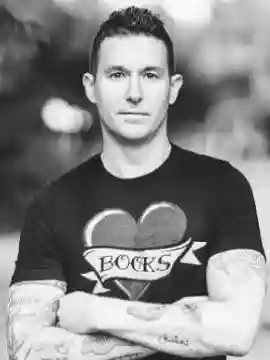

About the author

Joshua is the author of five novels, including Damascus, which The New York Times called “Beat-poet cool.” He’s also written Some Things that Meant the World to Me, one of O Magazine’s 10 Terrific reads of 2009, and All This Life, winner of the Northern California Book Award. Termite Parade was an editor’s choice on the New York Times Best Seller List. His memoir, Model Citizen was an Amazon Editors’ Pick. In his Hollywood life, he’s sold projects to AMC, ITV, and Amblin Entertainment.