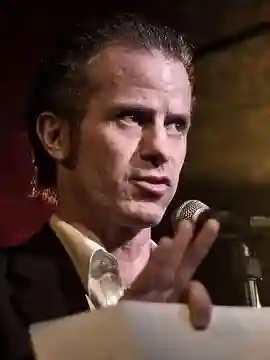

Photo by Craig Clevenger

I have two major pet peeves when it comes to dialogue. First, it bugs me when all the characters sound alike. Sure, with regional diction, accents, socioeconomic class, blah blah blah, it may be tough to distinguish between the Valley Dude speak of two high school kids, but not between those kids and their teachers or parents. Secondly, when characters speak with the same eloquence, or at very least the same style, as the narrator, i.e., the author, it rings false for me. One of the most valuable classes I had as an undergrad was a single semester of writing for the stage, during which we wrote two one-act plays. I still intended to write prose fiction, but writing plays forced me to hang the story on characters and dialogue.

To this day, I write all of my dialogue separately. In The Contortionist’s Handbook, I extracted all of the dialogue from the first finished draft, pasted it into a separate document in script format, what I call a “dialogue map.” No dialogue tags, narration, etc. I read through it out loud, re-worked it until I was satisfied, then dropped it back into the subsequent draft of the novel. With Dermaphoria, I wrote the entire first draft with no dialogue at all. Just narrative, with placeholders for the dialogue. Those placeholders had notes as to the nature of the exchange and the particular outcome, as well as any specific key phrases or lines I wanted to use. With each chapter, I wrote a dialogue map from scratch, worked on the dialogue separately from the novel (multiple drafts, etc., as though each map were a short play), then wove it back into the prose and worked on dialogue tags and breaking up the prose to accommodate it. In my current project, I’m writing all of the dialogue first with each chapter, to make certain that the chapter is driven by the voices and actions of the characters. Yes, it’s a lot of work, but worth it in my opinion. I’m very self-conscious about my dialogue. Will Christopher Baer thinks I’m crazy. He’s probably right. But the feeling is mutual.

Good dialogue is all about the author being invisible and letting the characters take center stage. It’s the difference between watching people on a screen, versus spying on them through the window, versus being in the room with them. Ideally, you want your reader in the room with your characters; experiencing your story as opposed to witnessing it (or simply hearing about it). Crafting realistic dialogue is a matter of time and practice, of listening to people and having an ear (and a love) for accents. While I have a few pointers on those things, they’re really up to the individual writer to work at. However, I have learned some very practical ways for the author to disappear when it comes to writing dialogue, methods that remove the one-way mirror between the reader and the story.

First things first. The fewer tags, the better. There are two basic reasons we tag our dialogue. First, to let the reader know that characters are speaking and, specifically, which character is speaking which line, so the reader stays oriented. Second, to convey the tone with which the character is speaking his or her dialogue.

I know the first reason, “to let the reader know that characters are speaking,” sounds obvious, but think about it:

He approached her nervously. “Good evening,” he said.

“Do I know you?” she asked.

“Good evening” is in quotes, so we know he said it; “Do I know you” ends with a question mark (or a mystery point, as a certain preschooler refers to it), so why tell the reader she was asking him something? In most cases, only two people are exchanging words and only one of them is speaking at a time. Yes, there are plenty of exceptions to this, but in my experience a reader can go at least five or six lines without getting lost before the author needs to step in with a single tag (maybe two) and remind them who’s speaking. Of course this depends on the nature and depth of the dialogue but again, the author can usually step out of the scene for far longer stretches than most people realize, which keeps as little as possible between the story and the reader.

The second reason, “to convey the emotional tone of the dialogue,” is a bit trickier. I’ll begin with a minor heresy: I love the word said and all of its variants, absolutely love them. There are other schools of thought but presumably you’re reading this for mine, so here goes. The criticisms I hear about said are usually that it’s boring, overused or doesn’t indicate the tone or delivery of the speaker. On the contrary, I find said to be like a period or a comma in that it does its job, gets out of the way and is promptly forgotten.

Of course it’s forgotten, you may be thinking, because it hasn’t done anything. What if two people are arguing, or in the midst of a tense negotiation, or a seduction (aka, a tense negotiation), or squaring off in a prison yard or talking in code? What if someone is shouting or whispering or gasping for breath? The reader needs to know these things.

Indeed, the reader does need to know. But the reader needs to find out these things for him or herself, without the author’s help, whenever possible. Comic book dialogue tags—cried, sobbed, gasped, shrieked, laughed, or my all-time most personally reviled, chortled—are very often physically impossible to do while speaking, though the colorful tag implies just such simultaneity:

“You’ll never work in this town again,” she laughed.

“I don’t think I’m going to make it,” he whimpered.

Yes, it’s possible to shout, bellow or sing a line of dialogue but in other cases, actively sobbing or laughing (or chortling) while talking can’t happen. They may happen around a character’s words, but not during.

Secondly, if you need to tell the reader the emotional tone with which the dialogue was delivered, then you should perhaps consider taking a look at the dialogue itself to see if the emotion is implicit in your choice of words:

“Get out of here and don’t ever come back,” he snapped.

versus

“Get out. Now. And don’t come back. Not ever.”

The difference is subtle, I agree. And sometimes the emotional tone and delivery of the line can’t be conveyed purely with your choice of words. So, what then? By appending a line of dialogue with a character’s action, you can convey the tone of the delivery by showing us their emotion rather than telling us about it.

Telling:

“It wasn’t his fault,” he sobbed. “My boy should never have been in that car.”

Showing:

“It wasn’t his fault.” He buried his face in his hands and turned his back to me. “My boy should never have been in that car.”

Remember, Strunk & White's Elements of Style says to “omit needless words.” Don’t confuse this with using fewer words than necessary. Sometimes more words are required to make your point, as in the second example above. However, none of the words in that second example are useless, because action tags in dialogue are remarkably efficient, pulling their weight on several fronts:

- They orient the reader as to who’s speaking, and they do so invisibly.

- Actions convey the emotion of the dialogue without resorting to cheap tells like sobbed or chortled.

- Tagging with action further reveal character through simple gestures or grand displays of behavior.

- And sometimes they can advance the story, as in, “See you on the ground, sucker.” He grabbed the briefcase and leapt from the rooftop.

Action tags are one of the reasons I’m so fond of characters smoking. The gestures surrounding smoking are elaborate to the point of ritual, and they vary from person to person. Think of the difference between how someone lights a cigar versus tamps open a box of cigarettes or hand-rolls their own. And how does the ritual of lighting a hand-rolled cigarette differ from sparking up a joint? Likewise for drinking... does your character chug from a bottle, sip from a martini glass or throw back a shot? And how do all of these things change when they’re speaking with a co-worker, a boss, a spouse or an illicit lover?

Keep in mind that while using action to attribute dialogue is a powerful tool, the dialogue still needs to be front and center. Too many updates as to who’s firing up a bong, cutting a line, removing their sunglasses or scratching a boil can overshadow what the characters are saying to each other, which is where your story happens. If I have a particularly long exchange and I’m trying to stay out of the reader’s way, I’ll step in after a volley of ten or twelve lines to keep the reader anchored; I’ll simply use “said” to keep things moving, especially if I’ve exhausted my references to beer chugging or burger flipping.

Let’s revisit *Lou, my short-order cook version of Marv, and all-around crash test dummy for examples from my classes:

The cracked vinyl of the booth wheezed beneath Lou’s girth as he sat down across from the customer, a bespectacled yuppie who held his fries with his pinkie extended.

“Can I help you?” The customer stopped in mid-chew with a mouthful of food, staring at Lou.

“I guess you can.” Lou cracked open a fresh beer and drained it in a single, prolonged gulp. “Darla, the pretty blonde waitress there who’s been so nice to you? Wiped the crumbs from your table here, brought you coffee. Probably called you ‘sweetie’ or ‘doll’ or something.”

“She’s been wonderful, yes. Great service.”

“You like the service. That’s good.” Lou crushed the empty beer can in one fist like a foil gumwrapper. “Darla tells me, maybe, you don’t like the way I cook.”

“No, no, that’s not it at all.” The customer fumbled for a napkin to wipe the grease from his fingers. "It’s just that my burger was a little underdone. It’s rare and I asked for medium rare. I’m sure you’re a wonderful cook, uh…”

“Lou.”

“I’m sure you’re a wonderful cook, Lou.”

“I get by, you know. But I’m always eager to learn.” Lou reached across the table and gently gripped the man’s shoulders with hands like twin catcher’s mitts. “Maybe you could show me. Just you and me in the kitchen. Nobody around. I got all my stuff back there. Meat tenderizers and knives and things. We could have us a little cooking lesson.”

Not one dialogue tag, not even said. Pretty neat, huh? Try nixing all of your dialogue tags, every one of ‘em, then re-read your scene. You’ll find that the exchange makes much more sense for much longer than you realized before you get lost at which point you can drop in a tag or some action to re-orient the reader.

*(The above passage is from the 200-Proof Storytelling lectures on status play, which I hope to make public at some point in the future. Those lectures were fairly abstract and as a result, I glossed over some of the dialogue tagging basics I’ve discussed here. This example came from a follow-up question to that lesson.)

Okay, enough lecture... let’s hit the lab:

Jerome saw Bethany waiting at the bar. He was ten minutes late, and he hated having a date wait for him. It was simply bad etiquette. He approached her nervously.

“Good evening,” he said.

“Hello,” replied Bethany.

“Have you been waiting long?” Jerome asked.

“Long enough,” she said.

“Can I get you a drink?”

“Got mine right here. But you look like you could use one.”

“The rain,” said Jerome. “It was impossible to get a taxi.”

“Is that what you want to talk about?” Bethany asked. “The weather? Taxis?”

“I’m not following you,” he replied.

“Why don’t you get yourself a drink,” she said. “Maybe two. Then decide what you want to talk about.”

Only two people talking with dialogue exchange of ten lines, all fairly short. Let’s anchor the reader at the beginning so they know who’s speaking, then let them fly solo:

“Good evening,” he said.

“Hello,” replied Bethany.

“Have you been waiting long?”

“Long enough.”

“Can I get you a drink?”

“Got mine right here. But you look like you could use one.”

“The rain,” said Jerome. “It was impossible to get a taxi.”

“Is that what you want to talk about? The weather? Taxis?”

“I’m not following you.”

“Why don’t you get yourself a drink,” she said. “Maybe two. Then decide what you want to talk about.”

Cool. From eight tags down to four and nobody got lost. Let’s cinch it a bit tighter. We want to anchor Bethany’s first line but to say that she replied is redundant.

“Hello.” Bethany glanced over to Jerome then back to her drink.

A few more words, yes, but they’re sparing me the patronizing replied and setting the stage with Bethany’s behavior. Still, it’s all fairly neutral. Let’s work on the emotional tone of the scene with some action. First, Bethany is going to wrap Jerome around her little finger:

“Good evening,” he said.

“Hello.” Bethany glanced over to Jerome then back to her drink. She ran her finger around the rim of the glass and smiled to herself.

“Have you been waiting long?” Jerome took the seat next to her.

“Long enough.”

“Can I get you a drink?”

“Got mine right here.” She gave Jerome a slow up-and-down with her eyes. “But you look like you could use one.”

“The rain.” He felt the heat rising in his face. “It was impossible to get a taxi.”

“Is that what you want to talk about? The weather? Taxis?”

“I’m not following you,” he replied.

“Why don’t you get yourself a drink,” she said. “Maybe two. Then decide what you want to talk about.”

Next, the same dialogue, but with different action tags. This time, let’s ice it down:

“Good evening,” he said.

“Hello.” Bethany glanced over to Jerome then back to the television overhead, absently fishing the olive from her martini.

“Have you been waiting long?” Jerome took the seat next to her.

“Long enough.”

“Can I get you a drink?”

“Got mine right here.” Her eyes stayed locked on the game. “But you look like you could use one.”

“The rain.” He felt the heat rising in his face. “It was impossible to get a taxi.”

“Is that what you want to talk about? The weather? Taxis?”

“I’m not following you,” he replied.

“Why don’t you get yourself a drink,” she said. “Maybe two. Then decide what you want to talk about.”

In either case, the dialogue could then be tailored slightly to fit with the tone carried by the action. In the first example:

“The rain.” He felt the heat rising in his face. “It was impossible to get a taxi.”

becomes

“Um, the rain. Outside, I mean.” He felt the heat rising in his face. “It was impossible to get a taxi. With the rain. I think I said that.”

Or in the second example:

“Is that what you want to talk about? The weather? Taxis?”

becomes

“Is that really what you want to talk to me about, Jerome? The weather and taxis?”

In summary, my first choice for dialogue tags is no tags at all. The reader knows that people are talking—that’s what quotation marks are for—and doesn’t need to be reminded who specifically is talking at every turn, much less informed that someone asked a question immediately following the question mark and closed quotes. When I think it’s necessary to either re-orient the reader after several lines without tags, and/or convey some emotion in the scene, I’ll follow a line of dialogue with a specific action. The speaker hands over an envelope, draws a gun or lights a smoke. Lastly, I’ll use said if I need dialogue further on in the exchange without going overkill on the bong hits, smiles, scratches and winks. Only if absolutely necessary will someone laugh or sob or whatnot, as long as it’s not implied as simultaneous. And they will never chortle.

In closing, some thoughts on accents and phonetic spelling:

Dropping articles, mixing up singulars and plurals in order to create the voice of someone speaking with a regional accent or a non-native language, well, that’s tricky (I’ll use accent as shorthand for accent, dialect and vernacular, inclusively). This goes triple for writing dialogue phonetically. You can often do wonders with this, conveying miles of characterization with just a few words. Conversely, you also run the risk of having someone sound like a bad stereotype or simply a parody of Borat. If characters are all speaking in a Southern accent but only the poor, lower class characters are written phonetically, the author could be exposed as myopic at best, racist at worst.

Writing in an accent requires not just a familiarity of it, but a sincere love of it. While most Americans can distinguish someone from England versus Scotland, we’re not always hip to the finer distinctions of speech from the British Isles, and they’re not always subtle. I lived in Dublin for a while and the difference between accents on either side of the river was night and day, as good as a completely foreign language in some parts of town. So when I read someone’s phonetic portrayal of leprechaun-speak, it makes me cringe.

Anthony Bourdain grew up on the East Coast, and in his hard-boiled fiction (yes, he's written a couple of really solid pulp crime novels) he replicates the Italian accent of his old neighborhood with love. Yes, he writes it phonetically, but without being condescending (although one could argue that he only does so with the mobsters and none of his other characters, but I don’t want to argue with Anthony Bourdain). Then there’s Dan Brown. I had an old flame in Paris years ago whose accent could melt wax at forty feet. So when I came across Dan Brown’s French characters, all of whom spoke like Pepe le Pew, it was all I could do to keep reading (I was writing a book review, so I forced myself).

The best, sure-fire method for conveying an accent is something I stole from William Gibson (my books are all in storage right now, so I’m going on memory). In one of his pieces from Burning Chrome, I think it was Hinterlands, he had a woman with a Texas accent. He spelled nothing phonetically, wrote no hee-haw dialect; her dialogue was all written in the Queen’s English, but the narrator simply said, She was from Texas. She had an accent where ice sounded like "ass." Gibson planted that in the reader’s mind from the beginning, which allowed the reader’s imagination to do the work without portraying the character like a hick. In short, tread carefully. If you're not completely confident in the authenticity of your accent, then steer clear of it.

I mentioned the redundancy of using asked following a question mark/mystery point, but didn’t say anything about exclamation points. I avoid them, even when characters are arguing. They’re best used sparingly, like Cindy Crawford’s mole. Yeah, it works. It gives her character and distinction. That’s why she only has one.

Finally, read your dialogue out loud. This is mandatory. I've heard different schools of thought on whether or not a writer should read all of his work out loud (Palahniuk's in favor of this; my first "editor" was not) and I happen to believe that a writer should do so, always. More importantly, I believe a writer should read his or her dialogue out loud without any narrative exposition, as though reading a stage play, at least once during the drafting process. Trust me, the flat notes, cut corners and unnatural phrases will sound like cartoon shrieks when they hit your ear.

Ladies and Gentlemen, start you Underwoods.

-Craig

About the author

CRAIG CLEVENGER is the author of The Contortionist's Handbook (MacAdam/Cage, 2002) and Dermaphoria (MacAdam/Cage, 2005). He is currently living in San Francisco, California, and completing his third novel.