Welcome once again to What Works & What Doesn't. Last month, we took a look at the dynamics and general criteria of a solid Act I via Terrence Malick's debut feature Badlands. We'll be doing more or less the same for Act II, and this time around, we're going to look at a movie that almost gets it right, but doesn't quite hit the mark. And in case you didn't notice the big header image and title right above this text, that movie is Showgirls.

Now, I'll admit, the phrases "gets it right" and "Showgirls" don't often appear in close proximity to each other. The film has a certain reputation for being, well, a steaming pile of crap. But look a little closer at the movie, and you'll see something a bit closer to a nearly-well-executed bit of campy satire on Western culture.

Yes, I'm serious. Let's get into this thing and I'll show you just how serious I am.

Act II Defined

As you well know (if you read this series), I typically turn to Robert McKee and his book Story (it has a longer title than that, but I just don't feel like typing it out again). It's one of the best books on screenwriting, as well as writing in general, so pick up a copy if you don't already own one.

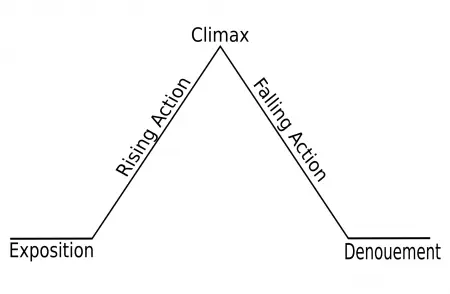

Now, as far as Act II and its major story beat, which we'll refer to as the Reversal, McKee has no concrete definitions to provide. The situation of defining the shape of a second act is similar to that of Act I, which we discussed last month with Badlands. Remember, too, that act structure is basically the same as the overarching story structure, outlined most effectively by the Freytag Pyramid:

Just as every story should rise to a climax with some falling action immediately following, so too should every act. With Badlands, we discussed the concept of the Inciting Incident, which McKee defines in two parts:

A story is a design in five parts: The Inciting Incident, the first major event of the telling, is the primary cause for all that follows, putting into motion the other four elements—Progressive Complications, Crisis, Climax, Resolution.

And later:

The INCITING INCIDENT radically upsets the balance of forces in the protagonist's life.

Now, while McKee and others insist the inciting incident can occur anytime during the first act—and the sooner the better—for me, placing the inciting incident closer to the end of Act I makes more sense, given that this moment in the story sets off every incident that will follow.

The same can be said for Act II's equivalent of the inciting incident, the reversal. Now, McKee speaks of this story beat as needing to occur in the middle of act two, and for this aspect, I couldn't agree more. Consider that a typical 120 minute screenplay will feature an Act I roughly twenty to thirty pages long, and an Act III about ten to twenty pages long. That means Act is going to be anywhere from 60 to 80 pages in length. That's a long haul. Having a "mid-act reversal," literally smack between the onset of Act II and its climax ensures the audience won't loose interest during the bulk of your story. It allows you to better ramp up to those big climactic moments. Otherwise, your story will just plod along to its major climaxes.

And while we're on the subject of plodding, let's begin our discussion of Showgirls.

What Works and What Doesn't

The Nitty-Gritty

Here's a brief history lesson on Showgirls, in case you're not familiar with it. Basically, it's a movie that cost millions of dollars to make, which included hefty sums paid out to screenwriter Joe Eszterhas and Paul Verhoeven, who were hot commodities in the 90s due to the wild success of their previous pairing, Basic Instinct (which actually does have a bit more going for it than that one infamous scene—you know the one I'm talking about).

Eszterhas's original idea was to effectively due Basic Instinct: Vegas Style!, but Verhoeven did extensive rewrites with the screenwriter, and changed the story to a modern-day All About Eve, incorporating the glitz and sleaze of Sin City (according to a 2015 Rolling Stone interview with the director). And because the studio, Carolco, had basically given Eszterhas and Verhoeven full creative control—figuring, no doubt, that whatever they churned out would make big bucks, particularly if it promised a ton of nudity and sex scenes (and it did)—the creative team was able to push forward without executive meddling.

Moreover, Verhoeven, having had the most miserable time imaginable with the MPAA trimming and hacking Basic Instinct, told the producers he'd only do the film if they planned to get an NC-17 rating from the get go. Carolco agreed.

Finally, Elizabeth Berkley won the lead role of Nomi Malone, the plucky young stripper who just wants to dance. This casting was enticing and/or luridly alluring to just about anyone from the age of 12 to 17, roughly speaking, for one reason: Berkley was most well-known, at the time, for playing the studious feminist Jessie Spano on the painfully-dumb-in-hindsight after-school series Saved by the Bell (say it with me, 90s kids: "I'm so excited! I'm so excited! I'm so...SCARED!").

This casting, plus the writer-director "dream team" of Eszterhas and Verhoeven, plus the intentional NC-17 rating and the promise of all the naked generated a significant buzz around the release of Showgirls. Carolco and its producers must've been on cloud nine (the future of the company actually hinged on Showgirls's success). But then they released the picture, and, well...it tanked. Miserably tanked. It swept the Razzie awards (the Oscars for "shit films"), critics ripped it to shreds, and audiences found the nudity and sex scenes to be mostly laughable and in no way titillating. This combined with the failure of Carolco's other cinematic gamble, Cutthroat Island, spelled the end for the production company.

So here's the question: is Showgirls really that awful, or was it just a victim of over-hyping? And the answer is: both.

See, the acting, the dialogue, and many of the scenarios in the film play out like a chewy ham 'n soap opera sandwich that tastes like utter garbage. But, all of that is by design. Verhoeven wanted his cast to gobble up the scenery, wanted the dialogue to be laughable, and wanted much of the action to be ludicrous. And in this way, one could almost consider Showgirls the apogee of intentional camp, a bordering-on-absurd lambasting of American culture as bright and garish as Las Vegas itself. (Aside: if you don't think Verhoeven is capable of such whip-smart social commentary, you truly haven't watched RoboCop. I'm dead serious.)

The problem is, Showgirls still isn't very good, and its primary problem lies in its story beats and climaxes, as well as its passive protagonist...

Slow Builds to Little Payoff

Showgirls is essentially a rags-to-richest-to-rags narrative. Nothing too original or spectacular, but of course that's okay, so long as the beats are present and they're nice and big (assume sexual innuendo here, if you must). For the most part, the beats are present in this narrative, but they don't feel big enough. This is especially true in the latter half of the film, but it's a problem throughout. I'll get to the exact reason why in a moment. First, let's quickly run through the big moments.

The Inciting Incident comes in the form of a lapdance/dry hump that Nomi performs for Zack (Kyle MacLachlan, who is really just kinda weird in this movie) while his girlfriend and star showgirl Cristal (Gina Gershon) watches. (Much of the movie is Cristal and Nomi battling each other, with the latter being one of the only people in all of Las Vegas, apparently, to tell the former she "doesn't know shit," which prompts Cristal to target Nomi as a frenemy/hate-lover.)

The lapdance leads to Cristal slotting Nomi in for an audition at the glitzy casino she works for, the Stardust (I think that's the name anyway, but it's really not that important). And even though Nomi is dismissed from the audition for refusing to put ice cubes on her nipples (yes, that is really the reason), Cristal ensures Nomi gets the spot.

Thus begins Act II. Nomi dances in the show, titled Goddess. The dance numbers are insane, purposefully not sexy in any way, shape or form, and downright hilarious. In between the performances, Nomi and Cristal continue to spar with each other (there are SO MANY shots of Nomi storming out of Cristal's dressing room), some dirty shenanigans go down, one dancer pulls a Tonya Harding on another dancer, etc. All of this culminates in Zack lusting after Nomi, and Nomi lusting after Zack, not because he's the entertainment director at the casino and he could potentially advance her career, but because she wants to make Cristal jealous. But that doesn't really matter, because Zack basically arranges for Nomi to become Cristal's understudy, which makes her a pariah to all the other dancers, given that it's perceived she slept her way to the top.

Cristal does get jealous, though, and threatens a lawsuit if Nomi becomes her understudy, leading to more feuding and storming out of rooms. All this comes to a head when Cristal makes Nomi look like a total chump during a rather weird biker/dominatrix dance number, prompting Nomi to push Cristal down some stairs. Cristal breaks her leg, can't do the show, and even though she's not the official understudy, Zack once again positions Nomi into Cristal's spot. She becomes the star of Goddess, her face gets plastered all over Vegas, and she's finally achieved her lifelong dream.

This moment is the reversal, though it isn't anywhere near the middle of Act II. It's actually closer to the end, and it poses a real problem, which we'll discuss in detail in a moment.

Now that Nomi's at the top of the game, she sees just how ugly it is. At a big party, Nomi's nice seamstress friend gets sexually assaulted by a big-time Vegas rocker and his two bodyguards. The thing is, everyone turns a blind eye to this horrid crime. Zack won't do a thing about it because this singer is part of the Vegas team, and you don't do anything to endanger the team. So, the climax of Act II is Nomi's decision to basically say "fuck it" and flush all her fame and fortune down the toilet by kicking the living shit out of the rapist singer (the bodyguards are spared her ire, for some reason) and skip town, hitching her way out of Vegas, the same way she got in (there's some humor with the Garth Brooks-loving dude that picks her up, but we won't get into that here).

Okay, now all of that might sound fairly exciting, yeah? Well, consider this: the total running time of Showgirls is a little over two hours, and the plot points I've described above are just about the most exciting things that happen within those 120 minutes. Put another way, Showgirls is just kinda boring. It could easily be paired down to 90 minutes, and it'd probably still be a bit stiff (no sexual innuendo there, I promise). This is the problem with placing the reversal later in Act II—it just takes too long for Nomi to ascend to the top of the game, and there's not enough of her seeing the seedy underbelly of her dream before she chooses to give it all away. In this way, the climax is abrupt and weaker than it could be.

Another part of this plodding pace: as I mentioned above, Nomi is far too passive a protagonist. I think part of this might be intentional—she's just a naive girl getting swept up in the Vegas lifestyle. And yes, she does eventually take the reigns of her own narrative when she pushes Cristal down the stairs and, later, decides to abandon her pursuit of fame and fortune and take very-clearly-written-by-a-dude vengeance on her friend's attacker. But everything else happens to Nomi. That lapdance/dry hump inciting incident? Okay, sure, she decides to sort-of go all the way with Zack while Cristal watches, but it's not specifically to advance her career as a professional showgirl. She only does it to piss Cristal off. The fact she gets an audition based on this lapdance is inconsequential. And when she has for-real sex with Zack in his pool (one of the more memorable scenes in the film—her crazy gyrations look like a seizure) there was no ulterior motive of getting Zack to promote her to understudy. It even seems less an act of making Cristal jealous. It just feels like an "eh, why not?" moment.

Basically, up until the end of Act II, Nomi doesn't really do much of anything. She idles, and the Vegas currents take her on her journey, and we're forced to float right along with her, waiting for things to happen. If Eszterhas and Verhoeven had taken a bit more time making Nomi a more active protagonist and moved the reversal to the middle of Act II, Showgirls could really have been the bonkers not-so-sexy romp through sleazy, morally bankrupt Vegas (read: America) that they'd intended. And though audiences have come around to the film in the twenty-one years since its release, it's still a so-bad-it's-good viewing experience, even if we know the camp and the overacting was on purpose.

What are your thoughts on Showgirls, specifically its second act? Do you think the action leading up to the reversal isn't boring at all? Let us know what you think in the comments section below.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com