Welcome once again to What Works & What Doesn't. Last time around we looked at Orson Welles's Citizen Kane and the construction of a sequence, the third largest building block of any screenplay (the second being sequences, the smallest being beats). This month, we're taking the discussion one step further by examining the Act, specifically the construction of Act I and its "inciting incident"—a climactic moment landing somewhere around page 22-30 (roughly speaking) that fundamentally alters the course of the narrative. As an example, we're looking and Terrence Malick's debut feature Badlands, a film that works quite well (crackles, really) on screen, but isn't quite as impactful on the page.

We'll get into the whys and hows of that in a moment. First, let's get on the same page by clarifying the specific terms we'll be dealing with in this column.

The Act and the Inciting Incident Defined

If you've been following this series at all, you'll know I frequently use Robert McKee's craft book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting as a solid overview of a screenplay's general mechanics. It's a great book, and worth the time if you've got it, especially if you're interested in a career in screenwriting in any capacity. Let's take a look at McKee's definition of an Act:

An ACT is a series of sequences that peaks in a climactic scene which causes a major reversal of values, more powerful in its impact than any previous sequence or scene.

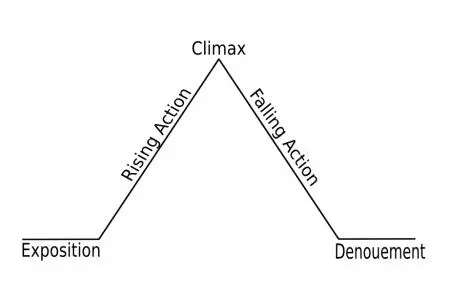

In other words, an Act must build toward something. Or, perhaps, rise toward a climax. This kind of structure should sound familiar to anyone who has ever studied the nuts and bolts of constructing a narrative, especially if you're familiar with Freytag's Pyramid:

Though this pyramid is meant to demonstrate the structure of a narrative in its entirety, it can also reflect the construction of an individual act. As you will see, Malick follows this logic in the first act of Badlands.

So real quick, before we get into the screenplay itself, let's turn back to McKee and his definition of the inciting incident, which he places as first among a series of five key story elements:

The Inciting Incident, the first major event of the telling [of a narrative], is the primary cause for all that follows, putting into motion the other four elements—Progressive Complications, Crisis, Climax, Resolution...

The INCITING INCIDENT radically upsets the balance of forces in the protagonist's life.

Okay, keep that and Freytag's Pyramid in mind as we head into Badlands.

Act I Analysis

We'll be looking at the "Final" draft of Malick's screenplay, dated 1972/1973. The writer opens with a fair amount of static action—the "15-year-old heroine" Holly (played in the film by Sissy Spacek) sits on her bed, petting her dog. In the scene description, we're told the year is 1959. Nothing else actually "happens" in this first scene, except that Holly delivers a hunk of exposition via voice-over narration.

Now, already we can see Malick potentially breaking the "rules" here, as the principle of "show, don't tell is especially pertinent to the craft of screenwriting. Billy Wilder's "ten rules of good filmmaking," originally published in Conversations with Billy Wilder by Cameron Crowe, addresses use of V.O. specifically:

In doing voice-overs, be careful not to describe what the audience already sees. Add to what they're seeing.

McKee weighs in on the topic as well:

The test of narration is this: Ask yourself, 'If I were to strip the voice-over out of my screenplay, would the story still be well told?' If the answer is yes...keep it in...If narration can be removed and the story still stands on its feet well-told, then you've probably used narration for the only good reason—as counterpoint

So, is that how Malick uses voice-over narration in Badlands? Indeed, even if ostensibly it seems as though he doesn't. To explain this, and to better grasp the mood Malick instigates in this very first scene, let's take a look at Holly's actual dialogue (delivered in the film by Spacek in a detached, almost monotone voice):

HOLLY (v.o.)

My mother died of pneumonia when I was just a kid. My father had kept their wedding cake in the freezer for ten whole years. After the funeral he gave it to the yardman... He tried to act cheerful, but he could never be consoled by the little stranger he found in his house. Then, one day, hoping to begin a new life away from the scene of all his memories, he moved us from Texas to Ft. Dupree, South Dakota.

Obviously, Holly isn't describing what's happening in the scene, so Malick is in line with Wilder's statement that screenwriters should "enhance" what the audience sees. Moreover, this dialogue acts as counterpoint, as McKee advises, in that what we see is a girl, in her bedroom, doing nothing more than petting her dog—an image, combined with the time period, meant to quietly capture 1950s innocence. And yet, remember that the year isn't 1951 or 1955, but 1959—i.e., the end of the 50s, at the precipice of widespread social changes and a general radicalization of ideas. This cultural shift is pertinent to Holly's story arc, in ways that will become evident soon (if you've seen the film, you already know what I mean).

Furthermore, look closely at this dialogue. It's easy, at a cursory glance, to see these words as embodying nothing more than a little backstory, an explanation of how Holly landed in South Dakota and was thus in a position to meet Kit (who Malick introduces in the next scene, played by Martin Sheen). Do we need to know that Holly once lived in Texas? No, but all the rest of the details are integral to Holly's frame of mind at the beginning of the narrative. Because ultimately, this dialogue isn't about moving to South Dakota, per se, but rather about her father, and about reading between the lines. What is Holly really saying here?

Take a moment to read the text over again. Note that when Holly refers to "the little stranger he found in his house," she isn't talking about the little figurines that adorn wedding cakes; she's talking about herself. She's hinting that her father secretly resents her, or if not that, she's at least all but spelling it out that their relationship is distant. And note the absence of the word "bad" in the line "hoping to begin a new life away from the scene of all his memories." Not "bad memories," not even "good memories," but just "memories," including any "good" times she and her father might have had together in that house. But even if we're meant to assume Holly means "bad memories," that still excludes her from the picture and ignores her emotional landscape. This is less a cold, detached statement of facts as a sort of despondence masking animosity.

So, to recap the first scene: Malick gives us the year, which is symbolically important to the character's mindset (as well as, of course, the fact Badlands is based on actual events that occurred in the 50s). We see this picture of innocence, a teenage girl petting her dog, with voice-over narration from the girl, dialogue that paints a slightly different picture, one that at the very least feels askew to an audience viewing this narrative for the first time. This is all part of our beginning values, the set of circumstances and knowledge that must change as the story progresses.

Malick continues setting these values in the next sequence involving Kit, "the hero, a 25-year-old garbageman." What's the first thing we see Kit doing in the script? Kneeling beside a dead dog.

Let that sink in for a second. Think about the juxtaposition here, between the innocent 50s portrait of Holly sitting in her bedroom, petting her live dog, and Kit, a garbageman, in an alley or on the street somewhere, kneeling beside a dead dog—a gritty, grotesque image that clashes with Malick's initial depiction of Holly. To add an extra layer of aberrance, look at Kit's first exchange of dialogue with his coworker Cato.

KIT

I'll give you a dollar to eat this Collie.Cato inspects the dog.

CATO

I'm not going to eat him for a dollar... I don't even think he's a Collie, either. Some kind of dog.

So, not only does Malick extend the "gross-out" factor and cast Kit further away from Holly's supposedly picturesque world, he also reveals more about the male protagonist than meets the eye (as he did with Holly in the previous scene). We see that Kit works as a garbageman, which unfortunately bears a negative stigma, as it is considered menial and mindless (which isn't altogether true). We also see that, although he is twenty-five years-old, he behaves a bit like a ten year-old. His dialogue is tantamount to "Betcha can't eat this dead dog!" He's a preteen, daring his friend to do something gross. And yet, Kit is instantly shown to be smarter than Cato (who is in his forties), since the latter believes a Collie is a separate animal entirely, and not a breed of dog.

However, during a "series of angles" (a montage) showing Kit at work, we don't see much more development of his intellect belong this initial glimpse. We instead see him just drifting along, digging through trash cans in search of valuables, balancing a discarded mop handle on his finger, stomping cans, and so on. When he finally ambles onto Holly's street, Kit finds her in front of her house, twirling a baton. Malick here establishes the aimlessness of both protagonists, a sense that neither one had anything better to do than meet each other. This wayward air even inflects Kit and Holly's first exchange of dialogue:

KIT

Hi, I'm Kit. I'm not keeping you from anything important, am I?HOLLY

No.KIT

Well, I was just messing around over there, thought I'd come over and say hello to you.

(smiling)

I'll try anything once.

This sense of "sure, why not?" continues, even though the couple begin a romantic relationship of sorts. Moreover, they begin to act irrationally or dangerously. Later in this scene, Holly tells Kit her father wouldn't approve of her hanging around a garbageman, so Kit immediately quits his job and goes to work at a feedlot. Holly, in turn, begins lying to her father about her whereabouts, all so that they can be together. And yet, they display about as much passion toward each other as a pair of strangers giving each other terse nods. In one of their first "dates," walking through town together, Kit points out a discarded bag, stating that if "Everybody did that, the whole town'd be a mess."

Most of their interactions go this way, and are ostensibly meaningless (though at one point Malick slips in a telling nugget of information about Kit: he hints that the character may have served in the Korean War). Not long after this "paper bag" scene, Holly narrates these words:

HOLLY (v.o.)

Kit went to work in the feedlot while I carried on with my studies. Little by little we fell in love...As I'd never been popular in school and didn't have a lot of personality, I was surprised that he took such a liking to me, especially when he could've had any other girl in town if he'd given it half a try.

On the one hand, this bit of dialogue breaks that rule of screenwriting mentioned above by briefly describing exactly what is happening on the screen (watching Kit working in the feedlot). But imagining that single line of dialogue absent from the text makes the entire speech feel incomplete. It's strangely necessary to hear Holly describing what Kit is doing, in the barest of terms, and with that same emotionless detachment displayed by the character throughout. It bolsters that sense of "sure, why not?" even as she and Kit "fall in love." Of course, this dialogue also reveals Holly's low self-opinion, and gives hints as to what it is about Kit that drives her so "wild." Their love is further defined in the next chunk of Holly's dialogue:

HOLLY (v.o.)

He said that I was grand, though that he wasn't interested in me for sex and that coming from him this was a compliment. He'd never met a fifteen-year-old girl who behaved more like a grownup and wasn't giggly. He didn't care what anybody else thought. I looked good to him, and whatever I did was okay, and if I didn't have a lot to say, well, that was okay, too.

Basically, these two just enjoy each other's company. They believe their feelings to be romantic in nature, but in reality, we question whether or not they simply get along well, that they're cut from the same odd, deadpan cloth. They even have sex about midway through the first act, and it displeases them both, generating a bit of tension between the pair. Holly especially thinks the whole thing was a kind of a bore, and is glad to have it over with, because she always feared she'd die before trying it. She might as well be talking about Rocky Road ice cream. Kit suggests, to commemorate the event, they smash their hands with a rock so that they'll associate the pain with sex and "never forget what happened" that day (i.e., so they'll never be tempted to have sex again).

Despite the tension, their physical engagement doesn't split Kit and Holly apart. They grow even closer, all the more "in love," leading to one of the most iconic scenes in the film:

EXT. FIELD

Kit releases a large red balloon into the evening sky. A small basket is fixed to the bottom of the balloon.

HOLLY (v.o.)

Kit made a solemn vow that he would always stand beside me and let nothing come between us. He wrote this out in writing, put the paper in a box with some of our little tokens and things, then sent it off in a balloon he'd found while on the garbage route.

(pause)

His heart was filled with longing as he watched it drift off. Something must've told him that we'd never live these days of happiness again, that they were gone forever.

Here we can see that not only is Holly (and presumably Kit as well) experiencing inward emotions she does not necessarily display outwardly, but that this love the couple feels for each other is poetic, almost beyond the confines of typical human experience. But it's also childlike and fanciful (that Malick uses music composed for children in this scene and throughout the rest of the film is no accident). There's immaturity wrapped up in their relationship, on the one hand because Holly, on top of only being fifteen years-old, appears not to have any friends and leads a mostly sheltered life, and on the other, because Kit seems stunted in his growth. He is observant and ponderous, but in the way a boy might be, and not in the fashion of a twenty-five year-old.

So at this point, you may be wondering, where is all of this headed? Well, let's look at what Malick has set up so far: we have two odd, semi-detached people who aren't much interested in sex but who nonetheless fall in love. There is an age gap of ten years between them, and because Holly is underage, and because Kit is a "wrong side of the tracks" guy, her father disapproves of this relationship. As such, Holly keeps her meetings with Kit a secret.

At this point, if you've never seen the film, does it seem obvious what will happen next? Have there been significant clues / moments of foreshadowing? Indeed there has, but they may not have registered as significant.

So what happens? Holly's father discovers she's been engaged in this secret relationship, and as punishment he shoots and kills her dog, the very one we saw Holly petting in the opening shot. Remember what proceeded this image? Kit kneeling beside a dead dog? Kit becomes a kind of harbinger of death here—by walking into Holly's picturesque 1950s life, he brings along with him the grit and grotesqueness of his world (which continues long after his garbage-hauling days are over; the feedlot is shown to be quite disgusting all around, including a dead and bloated cow that Kit actually steps on in one scene).

Where does this killing of Holly's dog lead? Kit attempts to reason with Holly's father, but he won't hear of it—Kit is nothing but a piece of trash to him. So, Kit does the only thing that seems rational in his mind—he gets a gun, enters Holly's house while she and her father are away, packs her things, and waits. When they return, he pulls the gun on Holly's father and tells the man he an Holly are leaving together. The man lurches toward Kit, convinced he won't pull the trigger.

But he does. He guns the man down in the living room, killing him. He swore he would always stand beside Holly, and he meant it.

This act of murder represents the film's inciting incident, because it sets into motion everything that happens in the film from this moment forward. The couple burn the house down and leave behind a recording that indicates they've killed themselves, in the hopes of misdirecting the police. Then they hit the road, planning to settle somewhere in the North, "where people don't ask too many questions."

End of Act I.

Does It Work?

Now, let's go back to Freytag's Pyramid. We can see that the entirety of Act I follows this structure. We have brief Exposition in which we meet Holly and Kit just before they meet each other. The Rising Action occurs as the couple spend time together and get to know one another, with Holly's father serving as the primary obstacle standing in the way of their relationship. Some tension arises between the couple, particularly following their disastrous sexual encounter, but overall their love for each other—as detached as it seems—intensifies. However, Holly's father discovers the relationship and callously murders her dog as punishment, leading to the Climax, or Inciting Incident—Kit's murder of Holly's father. The couple's slapdash plan of faking their suicides and burning down the house represents the Falling Action, with the Denouement encompassed by Kit and Holly leaving town for a new life. Though there is more story yet to tell in Badlands, if removed and examined individually, Act I is a narrative unto itself, which is exactly what any screenwriter should attempt to accomplish when crafting their own acts.

But while technically speaking, Malick has made all the right moves, can it still be said that this Act I works? Do his beats crackle, do they generate enough spark to keep the audience engaged?

On screen, the answer is yes, definitely. Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek are at the peak of their game in this film, and they wonderfully capture and exude their characters' detached oddness. This combined with the photographically stunning yet mostly static shots by cinematographers Tak Fujimoto, Stevan Larner and Brian Probyn, and the mostly xylophone-driven soundtrack makes for a decidedly unique viewing experience. On the bare-bones page, however, the writing comes across as almost too detached. I made it through my read-through for this column just fine, but I suspect that was only because I'd already screened the film on several occasions prior to reading the script.

This is hardly surprising, of course, given that Terrence Malick is a visionary, iconoclastic filmmaker who likely doesn't care much how his screenwriting skills translate to others. He hits all the necessary bullet points to keep a potential producer, for instance, reading / visualizing what these words could become, but he doesn't really go beyond what is expected on a basic, nuts and bolts level. And who can blame him really? Particularly since one of his goals was not to generate interest from a director (Malick directs his films himself). In this way, his screenplay's primary function is to serve as a the film's blueprint, as the skeleton awaiting organs and flesh—which is, really, the only function a screenplay is supposed to serve.

With this being said, Badlands is a good screenplay to study when considering how not to write one, especially if your only interest is screenwriting and not writing/directing—again, not because the beats aren't there, or because the story is bad, but simply because the script doesn't really crackle on the page the same way it does on the screen.

Any fans of Badlands here? What do you think about the structure of its first act? Is the inciting incident effective, in your mind? Let us know what you think in the comments section below.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com