With the English translation of Stieg Larsson's first Millennium trilogy novel, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, hitting American bookshelves in late 2008, a publishing trend took its first steps out of the primordial ooze and ventured onward. The release of the second and third books, The Girl Who Played With Fire and The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet's Nest, respectively, helped spread this trend further, solidifying its prevalence even today, seven years later.

What is this trend? Titling books either The Girl With (insert possession) or The Girl Who (insert action).

Now, of course, Stieg Larsson's English translators didn't invent this sort of title. Just like with her male counterpart who had things or did things, this eponymous Girl has been around for a while. To name a few examples: The Girl Who Owned A City by O.T. Nelson (1977), The Girl With The Silver Eyes by Willo Davis Roberts (1980), The Girl Who Heard Dragons by Anne McCaffrey (1985), The Girl With The Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier (1999) and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon by Stephen King (2005).

But search for The Girl With/Who in GoodReads, and observe a plethora of similar titles published mostly in 2009 and continuing exponentially thereafter. Here is a selected list of books titled either The Girl With... or The Girl Who..., with a few plot blurbs (courtesy of GoodReads) to demonstrate the vast and disparate landscapes the Girl has traversed. Some of these novels are the first in a series, just as with Larsson's work. Some sound genuinely interesting, and some even sport prestigious award nominations.

The List

The Girl With Glass Feet by Ali Shaw (2009—Fantasy)

The Girl with the Mermaid Hair by Delia Ephron (2009—Lit-Fic)

The Girl Who Threw Butterflies by Mick Cochrane (2009—Sports YA)

Molly doesn't want to be seen as 'Miss Difficulty Overcome'; she wants to make herself known to the kids at school for something other than her father's death. So she decides to join the baseball team. The boys' baseball team...

The Girl Who Chased The Moon by Sarah Addison Allen (2010—Lit-Fic)

The Girl Who Ate Kalamazoo by Darin Doyle (2010—Magical Realism)

The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making by Catherynne M. Valente and Ana Juan (2011—Illustrated children's book)

The Girl Who Would Be King by Kelly Thompson (2012—Fantasy)

Full Disclosure: Kelly Thompson works at LitReactor as a columnist.

The Girl with the Cat Tattoo by Theresa Weir (2012—Romance)

For cat lovers everywhere, this sweet, quirky, and delightful romance is about a young woman and her matchmaking cat. A little bit of mystery, a whole lot of whimsy.

The Girl With No Name: The Incredible True Story of a Child Raised by Monkeys by Marina Chapman & Lynne Barrett-Lee (2013—Non-Fiction)

The Girl With All the Gifts by M.R. Carey (2014—Horror/Dark Fantasy)

The Girl Who Lived by Susan Berg (2014—Non-Fiction)

As the sole survivor of a boating accident that claimed the lives of her parents and brother, Susan battled to find any positive meaning to life. Suffering from survivor guilt, Susan turned to sex and drugs before taking on the unexpected journey of teenage motherhood.

The Girl Who Never Was by Skylar Dorset (2014—Dark Fantasy, maybe YA)

Why This Matters

The first question anyone might ask is, "Could this be a coincidence?" A valid question. There are indeed numerous novels bearing either The Boy With or The Boy Who in their titles. The difference here is that these books have a scattered publication history, chronologically speaking—ranging from, based on another GoodReads search, the mid 1980s to present day. Moreover, there is a decided leaning toward the children's and young adult genres with these books. Compare that to the findings for The Girl With/The Girl Who novels, and you can see, even with the small sampling above, that many of the titles not only encompass children's/YA offerings, but plenty of works for adults as well. A clear pattern emerges here, one perhaps suggestive of publishers and authors alike capitalizing on a popular titling trend in the hopes of selling more volumes of their own publication.

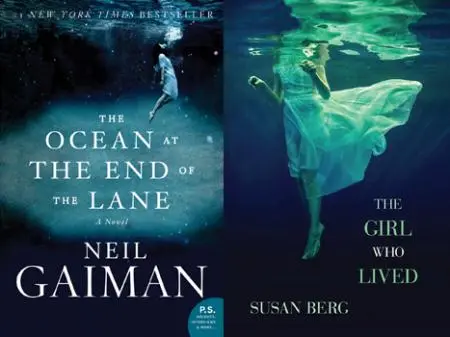

Which leads to the next hypothetical question: "So what?" Indeed. This sort of thing happens all the time, after all, and not just where titles are concerned. Consider the cover for the aforementioned The Girl Who Lived, and compare its design to Neil Gaiman's The Ocean at the End of the Lane, which appeared a year before Susan Berg's book:

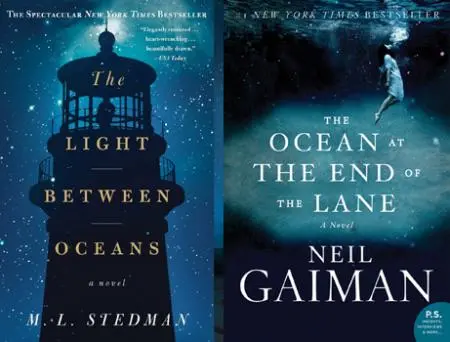

Now compare and contrast Gaiman's book title and the color palette and "watery" design of the jacket with M.L. Stedman's The Light Between Oceans, which came out a full year before The Ocean at the End of the Lane:

Do the visual similarities between these two novels and this one non-fiction title—all three released through different publishers and designed by different artists—cheapen any of the books overall? No, of course not. Writing books is an art, but selling them is pure business, and any "trickery" employed to generate greater sales is generally good, because it means the writer gets to keep living off his or her work.

Moreover, it cannot be categorically said that all The Girl With/Who books published after Stieg Larsson's Millennium series were pointedly motivated as a means of capitalizing on any titular similarities. Some undoubtedly were, but others were selected because the title simply fit the work—like Kelly Thompson's The Girl Who Would Be King, for instance, which suggests some of the conflict between its main characters and plays with gender-specific pronouns ("king" of course indicating a masculine ruler). The inspiration to select such a title could have also hit the authors or publishers subconsciously, and not specifically to generate more sales.

The third question then: is there any problem with this publishing trend? Mostly no, with a side helping of yes. See, the original Swedish title of Stieg Larsson's first Millennium novel did not translate to The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, but rather Men Who Hate Women, reflecting the book's exploration of patriarchal societies, systemic sexism, and rape culture, all of which the protagonist Lisbeth Salander actively upends. Larsson's second novel is actually called The Girl Who Played With Fire, released posthumously in 2006. Remember, Dragon Tattoo did not appear in English until 2008, which means Played With Fire had already been published. Now, this is pure speculation, but it is possible the publishers of the first English-translated edition (the UK-based Maclehose Press) chose both Dragon Tattoo and latterly The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet's Nest as a means of unifying the trilogy (for some reason, the overarching Millennium thread wasn't used to stitch them all together). The problem here is that The Girl Who Played With Fire references a moment in Lisbeth's childhood, when she was literally a girl, and not a grown woman.

So at first glance, the shift from Men Who Hate Women—which encompasses Larsson's overarching sociological examination through the lens of a complicated but no less powerful female protagonist—to The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo seems to fetishize Lisbeth, turning her into nothing more than a prepubescent pronoun with some mysterious, possibly slithery and sexy body art. But while the use of girl rather than woman is an oversight, the new title shifts attention away from the aggressive and victimizing men and back onto the women at large, the (would-be) victims represented by Lisbeth. Furthermore, this dragon tattoo, rather than being a point of sexualization, symbolizes Lisbeth's (and all women's) power, ferociousness and formidable nature—just in the way the mythical dragon is a creature both revered and respected, or feared and, thus, dominated. In short, the English title gives power back to Lisbeth, while the original Swedish unintentionally takes said power away.

More than this reinstating of power, the wild success of Larsson's novels and the subsequent trend of publishing Girl novels has affected a kind of cultural shift, in which it is now acceptable for men to read female-centric works of fiction. Consider this passage from i09 writer Rob Bricken's review of The Girl Who Would Be King:

To call Kelly Thompson's [book] a simple superhero novel would be to do it a disservice. To call it a wonderful coming of age story about two girls who happen to have superpowers makes it sound like it might be some sort of 'girls only' book, and that's not true either. What is true is that The Girl Who Would Be King is unique [sic], massively captivating story starring two characters who you'll want to see again when the book is over.

So whether the characters be gifted teenaged siblings vying for a throne, a badass yet damaged computer hacker, a junior high girl playing on the boys' baseball team, or a cat lady with a matchmaking feline, we're not only getting a wash of Girl titles, we're also getting a vast array of female perspectives and experiences exposed to a broad and diversely-gendered audience.

Now, if only they could grow up to be women rather than girls—a dim prospect given the recent news that the Millennium series will continue with a new author. We simply have to take the bitter with the sweet right now, and realize that our society fears change: we're just now, it seems, acknowledging the dragon as a force worthy of respect, but we're not yet ready to accept the full scope of its awesome power. With time, hopefully, we will see The Woman who had this, or The Woman who did that, captivating readers and raking in beaucoup bucks.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com