When the newly reformed LitReactor asked if I’d be interested in writing a how-to article on novellas, my knee-jerk answer (to myself) was: “How the hell should I know?” It’s a strange answer, one I should probably unpack with my therapist at some point, because — putting my own neuroses aside — I do know how to write them.

As of 2025, I’ve written five novellas: Bones Are Made To Be Broken, Standalone, How We Broke (with Bracken MacLeod), The Only Way Out Is Through, and You Can’t Save What Isn’t There — and only one of them was a whoopsie-daisy, didn’t see a novella there, son. With the other four, it was deliberate action; I wasn’t creating a short story or developing a novel, I was writing a novella, and I knew it.

On that note, allow me to show you how it’s done.

Key elements of a novella

First things first: the novella is something of an ambiguous form, so exactly how long should it be? Generally speaking, the accepted minimum length for a novella is around 15,000 words, and the accepted maximum length for a novella is 39,999 words. (Anything 40k and above is considered a novel.)

However, that’s only one side of the equation. The other side is content, and a novella is defined as much by what it has as by what it doesn’t.

📊 1 main plot, 1-2 subplots (at most)

While a short story can really only focus on one conflict (in television terms, let’s call it the A-Plot), a novella does have sufficient space to weave together a couple of different threads.

So a novella will obviously have an A-Plot — but it can also have a B-Plot, and maybe even a C-Plot. Too many secondary plots, though, drives you into novel territory because you’ll need the additional space in order to resolve those multiple plot threads.

Example: Of Mice and Men

For a more concrete example of that abstraction, let me put my English Teacher hat on and consider a novella pretty much every American is at least nominally familiar with: that American lit favorite, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck (and it’s only 30,000 words!).

If we think of OMAM in those television plot terms, the A-Plot is George and Lennie and the farm they want; the B-Plot is Curley and his cruelty and insecurity, particularly around his wife. (One could argue there’s a C-Plot, about the wishes of the farm hands, but 1) this is my English class and 2) Steinbeck’s focus on farmhands is sharper in another famous novel of his.)

In any event, both the A-plot and the B-plot unfold on their own until Steinbeck ties them together into a painfully tight (and tragic) knot. You can argue that you actually need varying plots in order to goose each other on. I mean, honestly, does the end of Of Mice and Men really work without both the A-Plot and B-Plot? The B-Plot underscores the resolution of the A-Plot. Either plot on its own would be an unsatisfying short story.

👥 Moderately drawn characters

In a novella, characters function in a similar way to plotlines. In short stories, characters are thumbnail sketches — just enough to understand why a character reacts a certain way.

With novellas, that thumbnail sketch becomes a moderately detailed drawing: you see how each character acts and some backstory as to why. But you don’t get the lavish, three-dimensional renderings giving you the full breadth of a character; that’s best saved for novels.

👧 “Goldilocks” theme

The question of why write a novella, in terms of theme and messaging, is perhaps self-explanatory: novellas are perfect for ideas that go beyond the simple sketchings and mood-pieces of short fiction, yet are too concise for thick, hefty novels.

In other words, they need to have a “Goldilocks” themes: those that aren’t too simple or too complex, but are instead just right.

I certainly found this to be the case with my own novellas. Again (except for the one novella that I wrote semi-accidentally), I went into each one with the sense a novella would be a perfectly proportioned medium for the ideas and themes I wanted to explore.

Also, on a practical marketing level, novellas are great for people who want something more engrossing than a short story, but don’t have the mental spoons to commit to a novel. This is increasingly true in a publishing marketplace that allows for self-publishing and digital reading. While contemporary novellas might struggle to find a trad-pub home, there’s always demand in the digital space — where you can publish whatever and however you want.

How to write a novella

I’m going to eschew certain basic writing things that you should know before you get here (sorry, explaining how to write a compelling character is another article). With that in mind, let me walk you through my essential process for writing You Can’t Save What Isn’t There.

1. Find a strong idea of suitable proportions

First off, ask yourself if your idea is actually novella-sized, or if you’ve had a non-novella-sized idea where you’ve thought: “Well, I can just modify it”.

In truth, you can’t over-stretch a small idea or overly condense a big idea, no matter how clever you think you are. A story that’s bogged down by excessive details and descriptions, simply to increase the word count, will be a story that’s not strong enough to convey its central idea. Conversely, skipping essential details, descriptions, and actions will render your story incomprehensible.

I said before that only one of my novellas was accidental. It was The Only Way Out Is Through, and the idea behind it (“What if a 1960s Virginia state trooper discovered that his colleagues worshipped a god that had grown tired of their faith?”) sounded simple enough I thought it’d be a short story. But the main character, Charlie, was much more interesting and developed than a short story’s thumbnail-sketch. In spite of that, it’s still the shortest of my novellas.

❤️ Think about the emotional proportions

When I write a novella, I want to focus on the emotional landscapes and inconsistencies in the characters' emotions. Consequently, I need enough time and space to let these landscapes unfold; this focus determines the exact length of the story.

You Can’t Save What Isn’t There came about because, as a parent, the worst thing in the world I can imagine is the death of a child (a concept I’ve explored in other novellas and short stories as well). Developing the story, I wondered what would happen if a grieving, at-wit’s-end father was given the choice and the power to make things infinitely better or worse in his world (you’ll see what I mean if you read it). What would he decide?

I could have written a quick short story about my main character receiving, putting on, and then being unable to take off a business suit, a Kafkaesque tragedy… but it wouldn’t have been very satisfying or comprehensible because there would be too many questions left unanswered from the initial idea. I mean, does just what I mentioned above make any sense to you? I needed to explore the whats, whys, and hows of this idea for it to work.

2. Consider structure and pacing — “how I’ll tell it”

Sorting out the structure — how to break your story up into parts — helps me organize my thoughts before I write. In terms of your own novella structure, think about:

- How will my plot build and progress?

- How might it escalate into major drama and, eventually, into the climax?

- Throughout this progression, what sort of details will bring tension and interest — that is, what will keep readers’ eyes locked on the page?

Structure is more commonplace, and more conscious, than it gets credit for in the “romantic” world of fiction writing. In fact, for many writers, every scene and chapter must have a specific purpose. Writers like me tend to think: “What do I need to happen here, so that the next scene or next chapter makes sense and pays off?”

If each section or part has a specific goal, this gives you (the writer) clear boundaries. No repeating information; keep specific elements to specific sections; lay certain groundwork early for a bigger payoff later; etc.

✅ Know what each section should accomplish

For You Can’t Save What Isn’t There, I decided that the beginning would serve as the introduction to the story’s world, its stakes, and its emotional logic. The middle was all about my protagonist acting on those stakes. The final part of the novella was the result of those actions.

And when I sat down to actually write YCSWIT, I kept this structure in place. I knew that in the first part, I really needed to grind in the hopelessness of my main character and juxtapose that with the choice he’s given. I had to drive those points home to ensure that the second part was logical and engaging, and that the final part was dramatic and impactful — keeping reading invested from start to finish.

3. Don’t pull any emotional punches

My novellas deal with the interior lives of people who I can imagine, but who — at least at first — I don’t actually know. My first drafts are me learning who they are. I want to understand my protagonist (I rarely write “heroes”) so that, when the weird and horrifying happens later, I can truly believe in their reactions and what would happen next.

This goes back to the emotional weight I’ve mentioned. Again, my instinct with a novella is always to focus on the emotional heart of the story:

- What is this character feeling?

- Why do they do what they do?

- Do they fully understand their own emotions and actions — or if not, will they arrive at that understanding before it’s too late?

I’m not one for a multitude of minor plots that somehow come together and connect (this can be satisfying in some novels, but not really in a novella — again, you don’t want to overextend the form). When reading or writing a novella, I just want to understand the thoughts and behavior of a simple but fraught person, under extraordinary pressure or circumstances.

🤔 Which elements will contribute to this?

As you settle on your novella-worthy idea and structure, consider what elements of it make you feel strong emotions. Which situations bring you to laughter or to tears, rage or contentment?

Incidentally, as you mull this over, you’ll already be developing scenes for your future story and how they’ll play out — even before you put fingers-to-keyboard. These are the elements that will make your readers feel strongly as well: we’re all human, after all, and certain feelings are universal even if we’ve never been in the engendering situations ourselves. I’ve made adults who don’t even have children weep about a fictional parent’s grief — and I revel in that.

4. Then write toward the vision you’ve created

By this point, maybe you haven’t opened up a writing program or settled on a regimen — but regardless, everything mentioned above is writing. Imagining, planning, and problem-solving are all as much “writing” as putting words on a screen.

In fact, everything above should be roughly worked out before you start the “work”. Maybe not every single tiny detail — part of the fun is saving something to be surprised about! — but again, you should have a firm idea of what scenes and emotional pinch points you want to hit, in which order. That way, when you finally sit down to write, you’ll have a solid map of where you want to go and how to get there.

💎 Start with what’s clearest to you, and go from there

I knew when I started writing You Can’t Save What Isn’t There that my main character would be an artist, and there would be a scene where he tries to take off the inexplicable suit and his chest would begin to bleed copiously (I could practically smell the hot, sweaty copper in the air). I knew my main character would see his dead child because of the choices he’d made, and it would bring the emotional house down when it happened.

My job, when I finally sat down, was working towards those moments — and others I won’t spoil — translating the pictures and sensory details I’d imagined into words. (I can smell the blood now and I’m glad I haven’t eaten breakfast yet.)

Getting to that point — the physical act of writing — is, in my opinion, the easier part of the process so long as you’ve planned things out. To be sure, when writing something as specific as a novella, you want to come in well-prepared in order to avoid the possibility of an idea failing on you… and not having the space to write yourself out of the corner.

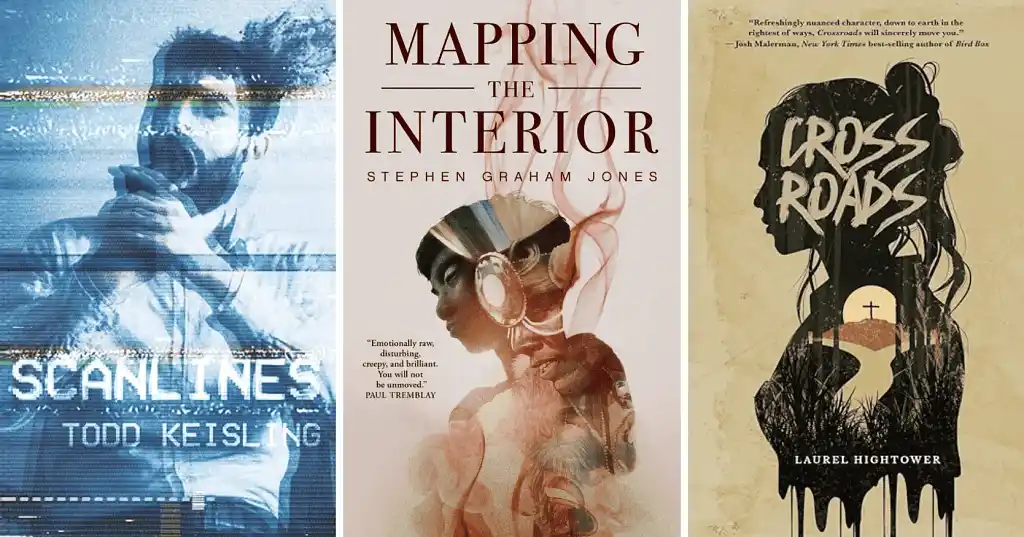

Novella examples to study

Having detailed my own process of writing a novella, you may wish to have some additional examples to go off.

There are three novellas that I think of as representing the best of the form — further illustrating why I write them myself. These are stories that understand the spacing and pacing they are available within the novella and they use it extremely effectively:

📹 Scanlines by Todd Keisling

Inspired by the true story of R. Budd Dwyer’s suicide on live television and mixing elements of urban legends and ghost stories, Keisling’s novella drives home, for me, what makes horror so compelling: the absolute helplessness to escape your fate, but also your absolute refusal not to try, anyway. Fair warning, this is a dark story, and it does not leave the reader unaffected.

🏠 Mapping The Interior by Stephen Graham Jones

Jones is a masterful writer of understated lines that sting your heart and emotion and mind. Here, Jones addresses cycles of family, possession (not necessarily in a horror sense, but to elaborate further would be a spoiler), and identity through a teenaged protagonist. That logline is a bit vague, but it’s better to keep it that way.

👩👦 Crossroads by Laurel Hightower

This novella utilizes grief horror in a way that I envy as a writer. After the world-ending loss of her son, a mother learns that death might not be permanent… if she wants it enough. In this novella, Hightower embarks on a soul-churning journey with the reader, exploring what it means to actually lose someone and how destabilizing and unfocusing it can be. I recommend it unreservedly.

This is just a small handful of works, but they showcase what I love about the format as a reader. And as a writer of them, I hope my novellas — particularly Bones Are Made To Be Broken and You Can’t Save What Isn’t There — function on the same wavelength.

Final thoughts on novellas

If I can leave you with just one final thought, it’s this: if you’re on the prowl to write a novella, make sure it’s actually what you want to do. Much like the Goldilocks approach to theme, it’s a middle ground. The work involved is more intense than that of a short story, less than that of a novel.

But that’s just on you, the writer. What about the audience? What is satisfying to them? Is your idea a brief exploration of a theme or what-if concept, or is it better suited as a single “episode” (aka a short story)?

It’s not something you can just blue-sky and imagine away, unfortunately. Some of it is going to come from failing — short stories that trail on too long or novels that peter out too soon, whichever is your preferred method.

But, through those failures, I’ve learned my process: the process I wrote about above. Nothing I’ve said here is a guarantee of novella success (whatever that is to you), but... actually, think of it like this: if you want to write a novella, I’ve gone ahead and scouted out the terrain.

There will still be some surprises (no land is completely knowable, and there will still be surprises for me when I go hiking this trail in the future), but I hope I’ve shown you the general way there.

So what are you waiting for? Get to it.

About the author

Paul Michael Anderson is the author of the collections BONES ARE MADE TO BE BROKEN and EVERYTHING WILL BE ALL RIGHT IN THE END, as well as the novellas YOU CAN'T SAVE WHAT ISN'T THERE, STANDALONE, and HOW WE BROKE (with Bracken MacLeod). He currently lives in Virginia.