If I were to ask you to tell me about the story you’re writing, you might start by describing the world it’s set in. How the culture is unique, or how the technology is different from ours, or how it’s a world where the gods are real. And before long, you’ll see my eyes glaze over, betraying the fact that I regret ever asking.

The real key to getting me invested in your story is telling me about your characters and the challenges they face. I’ll struggle to care about “a story set in a world where pies are passports” — but if you tell me about a prodigious baker who must set aside her traumatic past to bake her dying parents’ counterfeit travel documents, now you’ve got me interested (and salivating)! Even more interesting would be a gluten-intolerant immigration officer trying to foil her at every turn — creating a natural push-and-pull dynamic that keeps readers intrigued.

In this post, I’ll discuss the two essential characters you’ll need in any type of narrative: the baker and the immigration officer, more commonly known as the protagonist and antagonist. I’ll give you some examples and tips, and by the end, you should be ready to fill your own stories with unforgettable protagonists and antagonists.

What is a protagonist?

The lead character of a story is known as the protagonist. As with most literary terms, we can thank our friends, the ancient Greeks, for coining the term. The words prōtos (most important) and agōnistēs (actor) combine to describe the star of the show: your main character.

I firmly believe that all great stories are about people and how they behave in unusual situations. Following that logic, a story’s protagonist will almost always find themselves in brand-new territory, and how they react to this change will drive the narrative forward.

Are protagonists always the viewpoint character?

With books written in the first person, the narrator is almost always the protagonist. It makes sense, as we’re seeing the story from their perspective — and their first-person insights give us an intimate view of how they change as the narrative unfolds. Most third-person stories take a similar tack: the narrator will commonly focus closely on the protagonist, sometimes filtering the narrative through that character’s eyes (in a POV aptly referred to as “close third person”).

However, I could also point to plenty of books where the viewpoint character isn’t the protagonist. Many Sherlock Holmes stories are written from the perspective of his partner, Doctor Watson, who also basically serves as Holmes’s hypeman and hagiographer. In Moby Dick, our narrator is Ishmael (of “Call me Ishmael” fame), a crewmate under the command of the monomaniacal Captain Ahab — the book’s actual protagonist, whose antagonist is none other than the titular white whale.

In both of these cases, using the POV of a secondary character gives the actual protagonist a sense of mystique. Readers aren’t given free access to their every thought, and as a result, we have to puzzle out who our main character is — a challenge that most readers relish.

Types of protagonists

If I had to explain the concept of ‘protagonist’ to a three-year-old, I’d describe them as ‘the goody’ of a story. That is probably sufficient for a child, but as we age out of books about hungry insects and cheeky dogs, we start to see a whole spectrum of main characters — many of whom are far from being ‘goodies.’

The Hero

Okay, to be fair, this first example is your typical ‘goody’ — but that doesn’t mean they’re virtuous to a fault. However, they are still characters presented with challenges to which they must rise. For example:

🚀 Luke Skywalker in Star Wars: a farm boy who must rescue a kidnapped princess to help save the galaxy.

🇬🇧 James Bond in Casino Royale: a British spy who must infiltrate a high-stakes card game to bankrupt a Soviet financier.

🐇 Alice in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: a young girl who must adapt to an unusual new world in order to survive.

A hero, in this sense, doesn’t have to be out there trying to save royalty and/or the free world. The most important thing is that these heroes face challenges that have real stakes. As you’ll notice in each of the examples above, I make a point of including what will happen if the hero fails to meet their challenge. This element of authentic risk is the key to their hero’s journey.

The Anti-Hero

For fear of dating this article, I’ll refrain from making a Taylor Swift reference. Anti-heroes, in the context of literature, are protagonists who don’t possess the classic traits of a hero. They’re not outright villains, in the sense that they aren’t (usually) malevolent, but they do live in an ethical gray area. They might be cynical, selfish, or even outlaws — but they also tend to have strong goals and a moral code that stops them from becoming mustache-twirling baddies. For example:

🧪 Walter White from Breaking Bad is an aspiring drug lord trying to provide for his family.

🚣🏻 Tom Ripley from The Talented Mr Ripley is a con artist who covets the lifestyle of a playboy heir he’s been sent to retrieve, having never experienced luxury himself.

💃 Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair is a manipulative social climber who wishes to rise above her humble beginnings.

You’ll notice that each of these protagonists, on top of their negative qualities, also have genuine desires that readers can relate to. That sort of vulnerability, I think, is crucial to any good anti-hero protagonist. It doesn’t really matter whether they learn the errors of their ways by the end of the book — so long as their central motivations are believable and somewhat relatable, the reader will be hooked.

Hero's Journey Template

Plot your protagonist's journey with our step-by-step template.

The Actual Bad Guy

Bad guys get all the best lines. That’s why we’re so often drawn to stories where the lead character is an irredeemable ol’ so-and-so. Their intentions might not be pure, but all these villains need in order to be protagonists — other than plenty of screentime — is a goal, some obstacles, and something at stake if they don’t achieve their goal. For example:

🔪 Patrick Bateman in American Psycho is a murderous yuppie with middling taste in music. If he’s discovered by his colleagues or the police, that’ll put an end to his killing spree and lavish lifestyle (and stop him from getting that sweet table at Dorsia).

👨👧 Humbert Humbert in Lolita is a mega-creep teacher whose obsession with 12-year-old Dolores sees him steal her away from summer camp. But his desire to control and possess Lola puts him in danger of losing her (and his freedom, if there is any justice in this world).

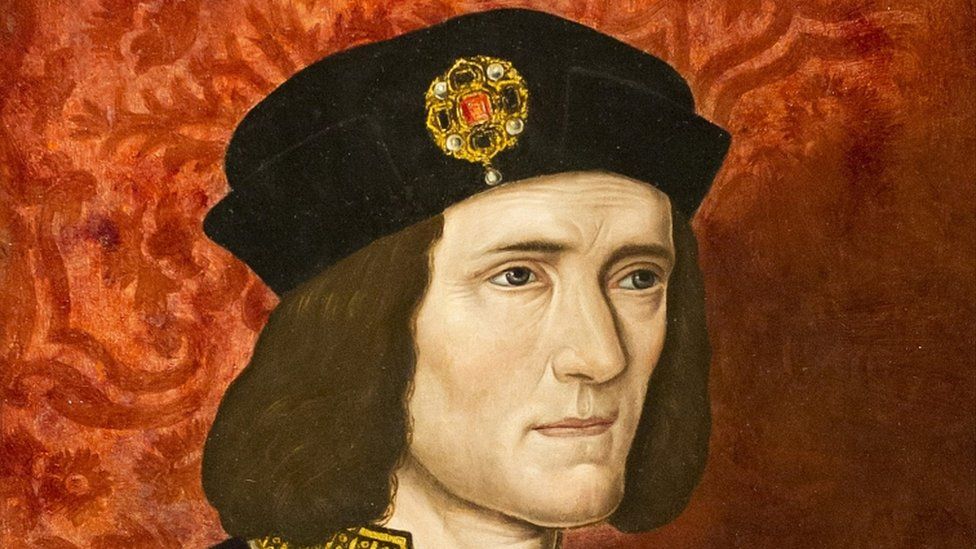

🐴 Richard, Duke of Gloucester in Richard III, is a villain who conspires against his own family to capture the crown. If his plans are discovered, he’ll lose the throne and pay the price for murdering his own nephews.

In all of these cases, the protagonists are pretty irredeemable — but because we are following their story, we know their motivations, and we understand what’s at stake, the story remains riveting. Remember, a reader doesn’t need to like the main character; they only need to care about what happens to them.

So, what have we learned from identifying these types of characters?

How to write a good protagonist

Let me summarize what we’ve gone over so far. All protagonists, regardless of how virtuous they are, should have three things in common:

- They must want something

- There must be something standing in their way of getting what they want

- There must be consequences if they fail to achieve their goals

To add some narrative spice to your protagonist soup, the ‘thing’ they want should almost be a false goal. In storytelling, we often talk about “wants and needs” — what a character wants often isn’t what they need. And as soon as they realize that, they can heal and find resolution. To keep the culinary analogies going, an amateur cook might want to win a televised baking contest, but what they need is to believe in their own self-worth.

On that note, now that we’ve covered the protagonists, I want to look at the flip side of the coin.

What is an antagonist?

Put simply, an antagonist is the character or force that is working against your protagonist. They’re the major obstacle preventing your hero from getting what they want. Referring back to our ancient Greek dictionary, the term roughly translates to ‘opponent.’

Every story should have an antagonist. Even if there isn’t an outright ‘bad guy’ hatching an evil plan to stop our hero in their tracks, there should be someone or something who’s threatening to thwart our protagonist.

Types of antagonists

Villains

Google ‘antagonists,’ and you’re likely to get pictures of out-and-out bad guys. These are the sorts of characters who are engaged in something morally questionable and must defeat the protagonist to achieve their wicked ends.

Of course, not all villains are despicable, alley-lurking cads who want to cause pain and suffering — they will, however, have justified their actions to themselves. For example:

🏢 Hans Gruber from Die Hard is staging a heist on a multinational corporation. He plans to blow up a skyscraper (and a few dozen office workers), but he justifies this action by imagining a future where he’s “sitting on a beach, earning twenty percent.”

🦜 Iago from Othello feels slighted when Othello, his commander in the Venitian army, promotes Cassio to lieutenant. Enraged at this perceived injustice, Iago begins to plot the downfall of Cassio, Othello, and Desdemona, Othello’s new wife.

🔨 Annie Wilkes from Misery is a psychopathic ex-nurse who has essentially taken her favorite author prisoner. But she has a good reason for keeping Paul Sheldon locked up: then he has to write her favorite character back to life.

Of course, not all stories are about two individual characters going head-to-head — sometimes there are greater forces at work.

Institutions

There are fewer “true” villains in fiction than you might imagine — people who do bad things for their own profit and enjoy bringing others down. Most of the time, the real antagonists that characters face aren’t individuals, but a larger group or institution.

Keep in mind that when stories do have institutional antagonists, we’ll often still see that institution represented by a character — one who exemplifies that group’s belief system or interests. For example:

🕶️ In The Matrix, the antagonist is the Matrix itself — a computer hive mind that has enslaved humanity to create a more orderly world. In the film, they are represented by Agent Smith, who is basically an antivirus program designed to root out a group of rebels against the Matrix.

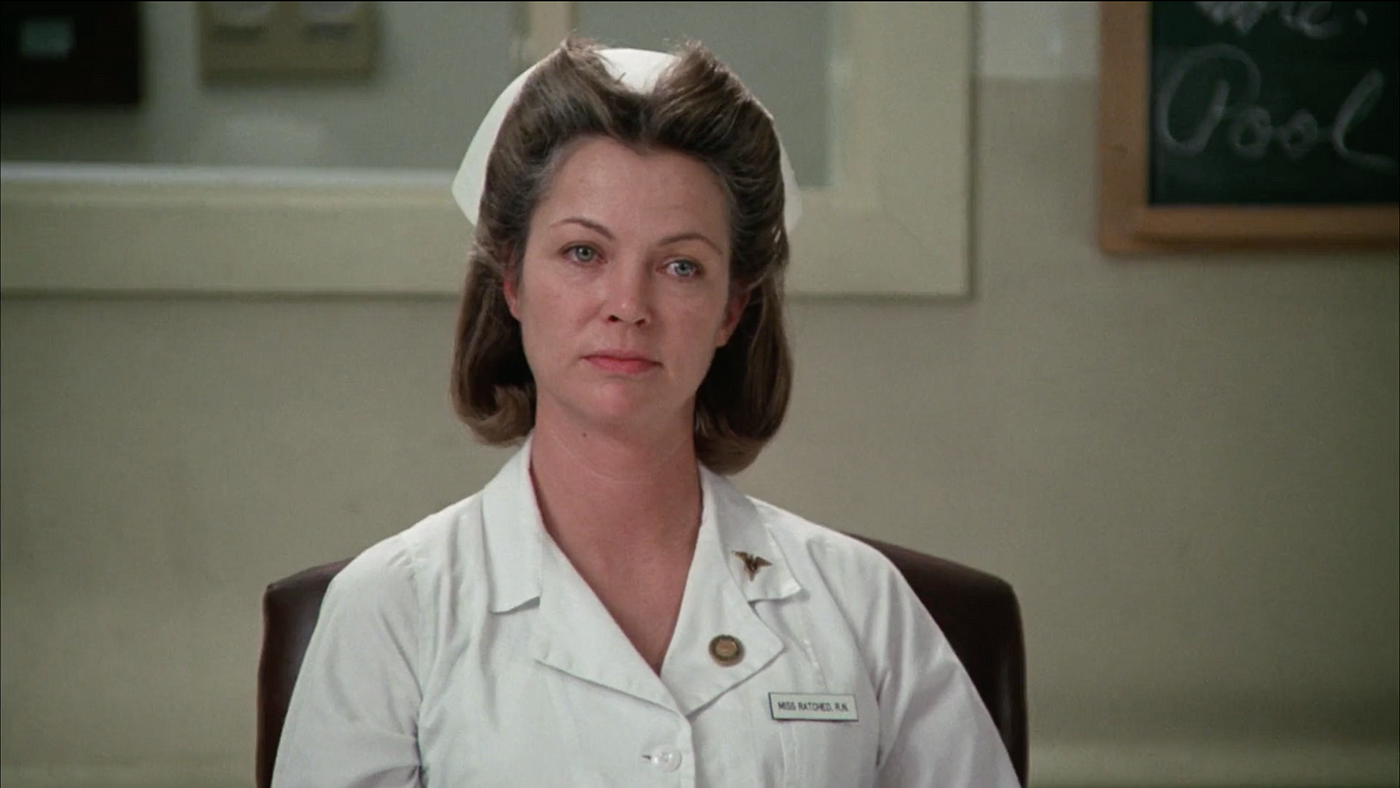

💊One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is about the cruelty and inhumanity of the psychiatric industry of post-war America. The appropriately named Nurse Ratched, who harbors total disregard for the freedom and integrity of her patients, is the human reflection of this institution.

Faceless institutions can be effective adversaries — while you can stop a person, it’s much harder to defeat an idea. But therein also lies the problem: it’s also hard to dramatize your hero’s fight against an amorphous enemy.

That’s why you often have these adversarial characters serving as representations. Such characters are often either zealots (and wholly believe in the philosophy of the institution) or functionaries who are going with the flow and ignoring the evils that they are helping to perpetuate. With the addition of someone your protagonist can battle against, your story now has a chance to develop some interesting conflict.

That said, not all antagonists belong in the material world. Sometimes, you have to fight the enemy within.

The Self

Wherever you go, there you are: your own worst enemy. And as in life, a character’s own worst enemy can often be found between the ears — in the form of personal flaws that prevent our heroes from getting what they want. For example:

🥊 In Rocky, our hero is a boxer preparing for a big fight against the world champ. But his opponent in the ring isn’t Rocky’s biggest obstacle; rather, it’s his own shattered sense of self-worth that must first be addressed.

🚀 In the original Star Wars film, Han Solo’s personal antagonist is not Jabba the Hutt or Darth Vader, but his own self-centered worldview. Only after he overcomes his own selfishness can he swoop in to save Luke from being blasted out of space near the death star.

If the forces of good and evil are battling within just one character, it can say something really profound about the human condition and our relationship with what’s right and wrong. However, you need to bear in mind that a purely internal conflict can also be somewhat dull (there are only so many scenes you can write of your character thinking quiet thoughts or shouting at the mirror).

That’s why many writers will personify that inner enemy by, again, using another character. For example, if your hero’s inner antagonist is their prejudice against immigrants, you might give them a colleague or a friend who is vocally xenophobic, which would allow your hero to see what that part of them looks like.

How do you write a good antagonist?

If you’re looking to write an antagonist that’s every bit as compelling as the hero of a story, you’ll want to consider some of the following:

- Give them a relatable motivation for opposing the hero. You can usually make this part of their backstory — bonus points if they have some sort of fraught personal history with the protagonist.

- Draw other parallels with the protagonist. Some of the best villains have many of the same goals as the heroes; they simply have a different way of getting what they want.

- Don’t make them too powerful. You want them to have strengths for the hero to overcome and weaknesses that can be exploited.

So, what’s the difference between a protagonist and an antagonist?

Wait... have you not read the first 2,000 words of this article? Fine, let’s summarize.

A protagonist is the leading character of a story. They are the one who the reader follows throughout the narrative, and their personal journey forms the bulk of the plot. The antagonist is their main opponent: the character or force that stops our protagonists from getting what they want. If written well, both characters will have believable motivations that readers can relate to (to some extent).

Remember, every story needs conflict — and that conflict should ideally be between characters to be compelling. In that sense, protagonists and antagonists are the most basic building blocks of any narrative. So pay close attention to how you develop these characters! With strong character foundations, your book, short story, play, or script can reach the full heights of its potential.

About the author

Martin Cavannagh is a writer, editor, and Head of Content at Reedsy. As the host of Reedsy Live, Martin has had the pleasure of sharing cutting-edge insights from some of the world's best editors, designers, marketers, and the occasional bestselling author. His newsletters, live streams, and blog posts reach millions of writers each month, inspiring the next generation of beloved writers.