To a certain extent, we’re all unreliable narrators of our own lives. The stories we tell are always slightly divorced from reality, whether it be by the distortion of perspective, personal bias, or a deliberate desire to conceal the truth.

Unreliable narrators in literature take this one step further. They’re not just describing life through their own subjective lens; they have been made deliberately unreliable by the author, in order to serve a specific purpose. In this article, I’ll discuss what an unreliable narrator is, the types you may encounter, and tips for writing them.

What is an unreliable narrator?

In literature, an unreliable narrator is a character who tells a story with a lack of credibility. There are different types of unreliable narrators (more on that later), and the presence of one can be revealed to readers in varying ways — sometimes immediately, sometimes gradually, and sometimes later in the story when a big revelation leaves us wondering if we’ve maybe been a little too trusting.

While the term “unreliable narrator” was first coined by literary critic Wayne C. Booth in his 1961 book, The Rhetoric of Fiction, it’s a literary device that writers have been putting to good use for much longer than the past 80 years. For example, "The Tell-Tale Heart" published by Edgar Allan Poe in 1843 utilizes this storytelling tool: the narrator recounts committing a brutal murder, all the while proclaiming his own sanity.

Fiction that makes us question our own perceptions can be powerful. Unreliable narrators can create a lot of gray areas and blur the lines of reality, affect the reading experience in many ways. They can

- Make the reader question everything: Fallible storytellers can create tension by keeping readers on their toes — wondering if there’s more under the surface, and reading between the lines to decipher what that is.

- Make for intriguing, complex characters: depending on the narrator’s motivation for clouding the truth, readers may also feel more compelled to keep reading to figure out why the narrator is hiding things.

- Drive an interesting wedge between the reader and the protagonist: Most of the time, as we read a novel, we “take our narrator’s word for it.” We’ll defer to and believe their version of events. So when this relationship is fractured, and we realize our narrator is unreliable, we feel wrongfooted — but intrigued. This distance in the usually close reader/narrator relationship can ask interesting questions about the nature of truth, the importance of perception, and about storytelling itself, which has made this an attractive literary device for authors.

- Hide a great twist: Sometimes, a narrator being upfront can take the sting out of a plot twist. In order to slowly drip feed readers information, an author may have their narrator deliberately withhold information from the audience, either through ambiguity, uncertainty, or straightforward deception. After all, if your narrator is the killer, you don’t want them to confess in the first paragraph!

So let’s dive into examples of not-so-trustworthy narrators from literature…

5 types of unreliable narrator

Just like trying to classify every type of character would be an endless pursuit, so is trying to list every type of unreliable narrator. That said, we've divided these questionable raconteurs into five general types to better understand how they work as a literary device.

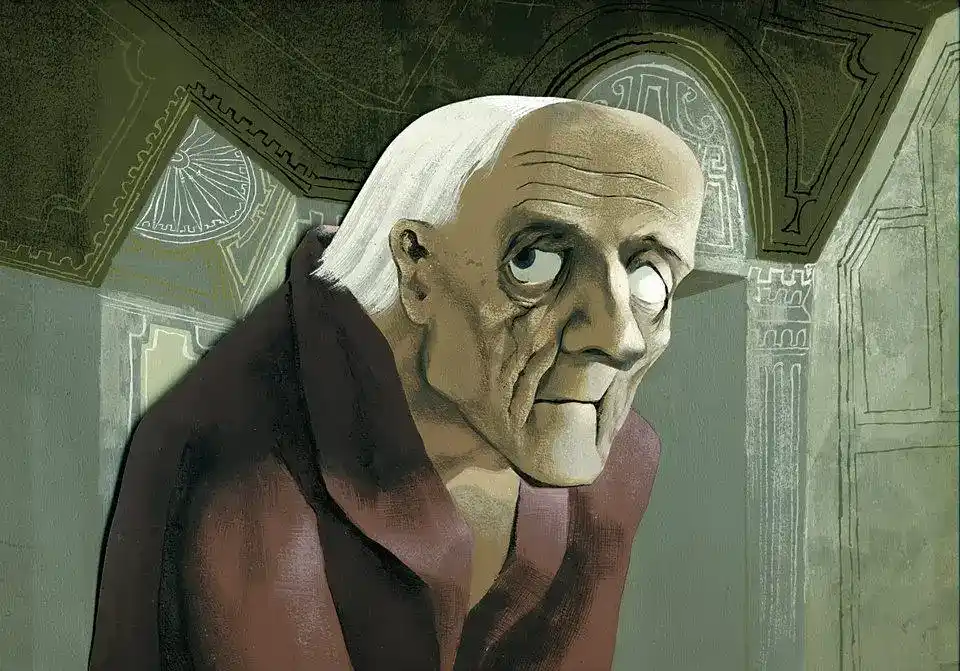

1. Deliberate

This type of narrator is intentionally lying to the reader because, well, they can. They have your attention, the viewpoint is theirs, and they’ll choose what to do with it, regardless of any “responsibility” they might have to the reader. This is almost certainly the most villainous of all the unreliable narrators we’ll meet.

A quick note about this kind of narrator: people want to read about characters they can connect with or relate to. This is one of the tricky parts of writing this kind of narrator: the character has to be compelling enough that we’ll keep connecting with them even if we suspect we’re being misled. We don’t have to necessarily like them, but we need to understand them.

Example: A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

The protagonist and narrator, Alex, is a notoriously brutal character who does not feel a sense of responsibility to anything or anyone other than himself. His lack of credibility feels deliberate and coy straight off the bat. He speaks 'Nadsat,' a dialect that confounds other characters and keeps the reader on their back foot. He is also a skilled manipulator who excels in getting others to let their guards down.

Alex is presumably aware that the narrative audience will be repulsed by his accounts, yet he repeatedly refers to the audience as “brother” — a term that implies familiarity and camaraderie. Readers can never be quite certain if they’re being confided in or reeled in as another one of Alex’s deceitful games. That said, Alex has an underlying humanity: his desire for individual freedom above all. So despite his flagrant lies, readers can still empathize with him.

2. Evasive

The motivations for this kind of narrator are often quite muddy — sometimes it’s simple self-preservation, other times it’s slightly more manipulative. Sometimes the narrator isn’t even aware they are twisting the truth until later in the book. Their unreliability often stems from the need to tell the story in a way that justifies something, and their stories are often embellished or watered down.

These kinds of contradictory characters whose mindsets aren’t clear can keep readers anxiously waiting for the narrator’s moment of clarity — drawing their own conclusions all the while.

Example: We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver

Narrated through Eva’s letters to her husband, We Need To Talk About Kevin takes place in the aftermath of her son committing a deadly attack at his high-school. It’s not easy to be totally honest with ourselves — especially when it comes to looking within and seeing where we might be at fault.

The only thing objective about Eva is that her accounts are subjective, and we are left to come to our own conclusions based on her descriptions. Was Kevin inherently sociopathic? Did Eva do her best as a mother or did she reject Kevin as an unwanted outcome? How much blame should Eva shoulder for Kevin's actions? We won’t find the answers in Eva’s letters, but they do prompt us to reflect on these questions in the first place.

3. Naive

Unlike the previous types, this type of narrator is not unreliable on purpose — they simply lack a traditional, “greater understanding.” This kind of unreliability can allow the reader to view your story with fresh eyes. The narrator’s “unorthodox” interpretations might only provide us with partial explanations of what’s going on, forcing us to dig a little deeper and connect the dots. These naive narrators can also encourage readers to take more significant notice of things we might’ve taken for granted.

Example: Room by Emma Donoghue

Five-year-old Jack is an often-quoted example of an unknowingly unreliable narrator. Jack is not withholding information from the reader or providing false information. He simply reports the facts as he sees them — however, as a child, his accounts often lack insight into the implications of what is happening around him. Because of this, even though Jack’s voice is a poignantly honest one, his narration is not a source of information that can be taken at face value.

4. Biased

Biased narrators are ones whose subjective perspective, prejudices, and beliefs are allowed to color the way they present the events of the story. They may emphasize or obscure certain facts, or be more or less sympathetic in their descriptions of others, depending on their own personal biases. This may be conscious or unconscious, and can be overt (for example, in displays of bigotry), or more subtle.

Example: A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

Despite the A Song of Ice and Fire series not being written in the first person, it is littered with examples of unreliable narrators. The chapters focused on Daenerys Targaryen, written in a third person limited perspective, are very much filtered through her subjective experience.

Daenerys truly believes herself to be a “liberator” and the rightful heir to the Iron Throne, and this is evident in the way difficult issues are flattened during her chapters. Episodes of violence, colonialism, and glimpses of tyrannical behavior are presented as justice being served initially — but, over the course of the fantasy series, we learn there may be far more to the story.

5. Impaired

Much like naive narrators, impaired narrators’ truthfulness is compromised not as a result of malice, but due to factors outside of their control. Perhaps due to mental illness, intoxication, or trauma, impaired narrators cannot give a complete and accurate account of events. Perhaps they have only flashes of memory, or perhaps their memories are distorted by some kind of health issue. This may be just as frustrating for the narrator as it is for the reader, and the narrative may be devoted to them recovering their memories, or trying to return to reality.

Example: ‘Momento Mori’ by Jonathan Nolan

This short story, which went on to be adapted into a feature film by the author’s famous brother, is a classic example of the impaired narrator. The protagonist Earl is suffering from ante-retrograde amnesia: he cannot create any new memories, the result of a brutal attack which also took the life of his wife. Earl uses notes and tattoos as tools to try and retain memories, as he seeks justice (and revenge) against the men who destroyed his family.

Meet Reedsy Studio

Master POV, character development, and plot beats in the writing app made for authors.

Should you use an unreliable narrator?

Unreliable narrators can be an opportunity to create engaging stories that misdirect and surprise the reader. They’re a valuable asset to mystery and psychological thriller writers in particular, but they can be useful to any author who wants to keep their readers guessing, and get them actively involved in the hunt for the truth. If you want to pose questions of reality, subjectivity, and fact versus fiction with your story, you may consider using an unreliable narrator in your writing.

However, there are several challenges associated with unreliable narrators. An unreliable narrator breaks the conventional relationship of trust between a reader and a storyteller. You don’t want to shatter that trust entirely, because you’re likely to alienate the reader. It can be difficult to write unreliable narrators that are still compelling, especially if you also want them to be likable. Make their untrustworthiness too obvious, and you run the risk of losing your audience. After all, why should readers want to hang out with a liar for the course of an entire book?

3 tips for writing unreliable narrators

It’s certainly no easy feat to pull off an unreliable narrator. If you still think you want to take a crack at writing one, read on for some top tips.

1. Make their unreliability important to the story

If you’re going to take the risk of undermining the reader/narrator relationship, make sure you’re doing so for a reason. If your narrator is just a liar without it serving any purpose to the plot, you’re probably just going to confuse — and irritate — your readers. So, before you start making your protagonist a slippery suspect, ask yourself why you’re doing it, and if it’s really the best way to achieve your narrative goal.

2. Don’t tip your hand too early — but don’t drop a bombshell out of nowhere

If you make your narrator’s credibility suspicious too early on, you’re basically giving the game away. By letting readers know the narrator can’t be trusted within the first act, you’re essentially giving them permission to check out, and deflating any tension you’ve built up.

Equally, don’t cheat the reader. Great novels inspire readers to come back and find new meaning and elements they hadn’t yet discovered the first time. This can be especially true of stories told by unreliable narrators. If you employ this literary device gradually throughout the novel, ensure you leave clues for your readers along the way.

Drop hints that make us question the validity of our source and have us eagerly reading to find the next clue that will act as another part of the story-puzzle. If you suddenly reveal out of nowhere that the narrator hasn’t been giving us all the facts in an abrupt twist, readers will feel they have been cheated.

3. Drop some red herrings to throw readers off the scent

We’ve already discussed the importance of leaving clues for your readers to help them figure out there’s more to the narrator than meets the eye. But to make it less likely that your audience will see right through your naughty narrator, why not try and distract them with some anti-clues?

Perhaps your narrator is treated as an upstanding citizen by those around them, or is shown to have a clear sense of right and wrong. Maybe they’ll go as far as The Great Gatsby’s Nick, who tells readers within the very first chapter that he’s a shrewd judge of character — only to go on to display some less-than-shrewd behavior.

Whether you like your unreliable narrators naively oblivious, or deliberately duplicitous, I hope this guide will have equipped you with all you need to spot them, categorize them, and even create one of your own. Or do I?

About the author

Laura Kerridge is a writer from London, and holds an BA in Classics from Cambridge University. She has contributed to notable platforms such as Litreactor, The Bookseller, and Unbounce. For over three years, Laura ran the popular weekly Reedsy Prompts contest and PROMPTED Magazine.