Quite often people ask me about the essential elements of a short story (or novel)—what are they missing, why does it feel incomplete, is there a reason it doesn’t resonate when it’s done? Most likely, they are missing one or more of the essential dramatic elements. So let’s discuss them in detail and see what we can do to improve your writing. I’ll be talking about short stories here, but you can apply all of this to novels as well.

DEFINED

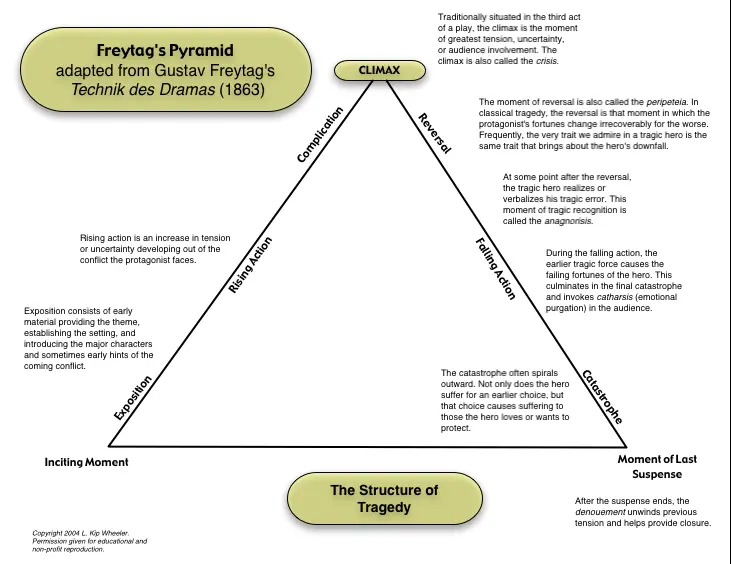

From Wikipedia: “Many scholars have analyzed dramatic structure, beginning with Aristotle in his Poetics (c. 335 BC). In his Poetics the Greek philosopher Aristotle put forth the idea that a whole is what has a beginning, a middle and an end.” And in Greek and Shakespearean terms that would also include five acts (of a play) which are “exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.” Let’s dig in a little deeper.

EXPOSITION

This is where the story begins. It is your narrative hook, the tip of the iceberg, early hints at theme, character, setting—and if done right, the conflict. This is where your inciting incident happens, that moment in time, that tipping point, beyond which things will never be the same. Whether your story is a straight line, a circle coming round, or some other structure, you have to start someplace. As mentioned in previous columns, starting in medias res, Latin for “in the middle of things,” is a great way to grab your audience’s attention. You are setting the stage here, so paint a picture, give us the backdrop, and start the thread (or threads) that will run through your narrative. I can’t tell you how often I’ve stopped reading a story because the opening paragraph was random, boring, or confusing.

RISING ACTION

Well, it’s pretty much what it sounds like, right? Things heat up, they get tense, the action intensifies, and the plot becomes more complicated, layered, and urgent. In order to do this, you must actually make things happen, you must move a character from place to place, follow their motivations, do what feels natural and right. There is an air of uncertainty—should your hero fight or flee, should your criminal kill or hide, should your child ask for help or take on the giant spider by himself? If you find that after a couple pages (for a story) that nothing is really happening, that your character isn’t physically moving, or mentally trying to solve something, then you may be spinning your wheels. You should be falling down the rabbit hole, life is getting more complicated, it’s going to get much worse before it gets better. This is often the longest part of your narrative, and usually, the most important.

CLIMAX

Sure, this is only the “third act,” so go ahead and make jokes about it happening too early, but this is the peak of your story, the top of the mountain, the greatest weight, the most tense moment—as dark and deep as it gets. Now, just because it’s the third act, it doesn’t mean that all five parts of our drama here have to be of equal length. Maybe the exposition is a third, maybe the rising action is half, and maybe the climax does come closer to the end. Often the last two acts can be very short—a page, a paragraph, even a sentence. The climax is when it all hits the fan, and if you’ve done your job, there will be a reversal.

FALLING ACTION

This is where your reversal starts, the change—for better, or for worse. The man who couldn’t sleep remembers why—it was a murder he committed years ago, haunting his waking life, and now he has remembered it all, and…what? Will he kill himself, will he try to make it up to whoever is left alive, will he vow to be a better man, committing his life to noble acts? Something has to change, though. Otherwise, why did we go through all of this? It will be only a vignette. Things have gone from bad to worse, they will never be the same again, it is all revealed, it is all up front, the darkness, the crime, and the betrayal. Your hero has realized his or her tragic error—what now?

RESOLUTION AND DENOUEMENT

This is the point in the story where we feel a sense of catharsis, an emotional purging—justice has been served, vengeance has been dealt. This is where the story really has its impact, where everything feels right, settled, and complete. Denouement is a French word which essentially means, “to untie,” as in a knot. It is here that the actions spiral outward affecting more than the hero, but also his family, loved ones, and his friends. We see the full range of the damage that has been done, and the epiphany of the righteous acts. We find closure in the final words, the final thoughts of our protagonist, and are left with something to chew on—a philosophical idea, a new set of behaviors, or a mirror held up to our own acts and deeds.

APPLIED TO A STORY

One of the stories that I’ve dissected here at LitReactor.com is “Twenty Reasons to Stay and One to Leave,” which was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Refer to my Storyville column on that bit of fiction if you like (it’s a very short story, a quick read). Let me take a moment to see if I indeed hit all of the stops along the way, writing a complete short story. Come with me, this will be fun.

WARNING: SPOILERS

Exposition/hook: “Because in the beginning it was the right thing to do, staying with her, comforting and holding her, while inside I was cold and numb, everything on the surface an act, just for her.” The title is what really gets us started—these are reasons that our protagonist has chosen to stay. It’s not a bad hook, as it hints at what’s to come—it’s the right thing to do (why?), he’s holding and comforting her (something went wrong), he’s cold and numb (in pain, and denial), acting stronger than he really is. Luckily in the second sentence we get more information that further reveals what this story is all about.

Rising action: “Because I couldn’t go outside, trapped in the empty expanse of rooms that made me twitch, echoes of his voice under the eaves, and in the rafters.” This is the second sentence. The echo implies that “he” is gone. We don’t know yet who that “he” is. We get the razorblades next, her need to kill herself (the wife) and some bizarre imagery of her with a doll at her bare breast, so this is heating up, just five sentences in. Then we get the imagery of the father missing his son, the wife saving her husband in the past, Matchbox cars, and breakdowns, and loss.

Climax: This is hard for me to pinpoint, but I think it’s when we realize that his son has died. And for me, that is probably about line fifteen, when we’ve been told several times, hinted at the fact that their boy is dead, and there is this, “Because I wasn’t done talking to my son, asking him for forgiveness.” Can a father sink any lower? Can it be any more compelling and sad?

Falling action: To me it is only three lines, that moment when everything in the story flips. We finally hear the word casket, and it confirms our worse fears: “Because I didn’t believe that we were done, that our love had withered, collapsed and fallen into his casket, wrapping around his broken bones, covering his empty eyes. Because I didn’t hate her enough to leave. Because I didn’t love her enough to leave.” But he will, in a second, right? That’s the title of the story, these reasons to stay, and the one reason to leave. This has gone from being a selfish act, his leaving, to being a loving act. That is your change, your reversal.

Denouement: “Because every time she looked at me, she saw him, our son, that generous boy, and it was another gut punch bending her over, another parting of her flesh, and I was one of the thousand, and my gift to her now was my echo.” This is coming full circle, we have the opening hook, that something is wrong, he is giving us reasons for staying, revealing bit by bit what has happened. It has intensified, reached a climax, and then faded into an understanding, an epiphany, and that revelation is that he must leave, that this is his gift to her, to not be an echo of the boy, a shadow of him, to not remind her of what they have lost every time she looks at her husband, to not be one of the thousand cuts that is slowly killing his wife. And in that act, in that change—there is freedom. You can breathe now, as a reader, at least that’s how I feel. This horrible tragedy, these dark moments, they will stop (or lessen), because now he will leave, and they can both move on with their lives, because they are beyond repair, they cannot stay together and heal.

IN CONCLUSION

I know that I’ve thrown a lot of technical terms at you, a lot of boring academic teaching going on here, and it’s easy to get confused. It doesn’t really matter exactly where each of these parts falls, how long they last, or how they overlap—but you should be able to look at your own work, analyze it, tear it apart, and see what’s missing. Beyond the characters, beyond the dialogue, the setting, and the plot—if you’re able to weave all of those elements into this structure, you will most likely reap great rewards. Look at your story (or novel) and ask yourself what’s missing? Quite often it’s change. There is no resolution, there is no epiphany that has allowed your protagonist (and your readers) to come to an understanding, to learn something—becoming a little bit wiser, deeper, and prepared for future events, good or bad.

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.