Note: This column isn't meant to be an exhaustive history of folk horror, but rather a broad overview of the subgenre.

We've been seeing the term "folk horror" bandied about lately in reference to Ari Aster's new film, Midsommar, about a group of American vacationers encountering a strange Swedish village with even stranger customs. This follow-up feature comes only a year after Aster's impressive debut Hereditary hit theaters, a film that also fits neatly into the subgenre. These two films combined with The Witch represent a kind of triumvirate of the folk horror revival prevalent in major film releases since 2015, and includes everything from Adam Wingard's remakequel Blair Witch (2016) to Jordan Peele's breakout hit Get Out.

But what is folk horror, exactly?

Filmmaker Piers Haggard first used the term in an interview with Fangoria in 2003 to describe his film The Blood On Satan's Claw (1971)—one of three films released in a five year timespan that many consider to be the primary progenitors of cinematic folk horror, the other two being Witchfinder General (1968) and The Wicker Man (1971). Labelled the "Unholy Trinity" by numerous critics, Mark Gatiss later discussed them in the 2010 documentary A History of Horror (a production which further popularized the term "folk horror"); Gatiss highlighted the films' "obsession" with landscape and folklore, and while this is certainly true of all three, it is perhaps The Wicker Man that best exemplifies what we now recognize as the subgenre’s basic tenets: occultism, rural/remote locations that generate feelings of isolation, and slow-burn narratives of psychological tension that culminate in a horror-charged third act/climax, usually involving a sacrificial ritual of some kind.

While the term initially only referred to film, there are plenty of literary antecedents and predecessors to the "Unholy Trinity," primarily belonging to the "weird tale" camp of horror. Both The Wicker Man and Witchfinder General were loosely adapted from novels—by David Pinner and Ronald Bassett, respectively—but the oldest works that could be considered folk horror come from early 20th century UK writers M.R. James, Algernon Blackwood, and Arthur Machen, all of whom wrote of faraway-yet-close countryside landscapes imbued with ancient terrors. Of particular note are Machen's novella The Great God Pan (1890) (for which LitReactor's George Catronis lavished great praise), James's short story "Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad" (1904), and Blackwood's novella The Willows (1907). Another significant example of early folk horror was Dracula writer Bram Stoker's 1911 novel The Lair Of The White Worm, which, like the aforementioned previous works, deals with occult, decidedly non-Christian happenings in a remote locale.

Across the pond, in America, H.P. Lovecraft produced story after not-so-thinly-veiled racist story that, combined, popularized what would later be labelled "cosmic horror," a subgenre that emphasizes the cold indifference of the universe beyond our puny planet and terrors so grand they have the power to spark instant insanity in our feeble human minds. Many of his works involved traveling to remote locations, including his seminal novellas The Call Of Cthulhu (1928) and At The Mountains Of Madness (1936), among others, and at least one of Lovecraft's tales, "The Festival" (1923) presented the idea of occultism occurring on a wide scale, with seemingly every member of a small town or village being involved in a supernatural conspiracy. This is of course an important element of The Wicker Man, though it seems neither Ritual author David Pinner nor the film's screenwriter Anthony Shaffer were inspired by this or any other Lovecraft story, or, if they were, they never mentioned it in interviews.

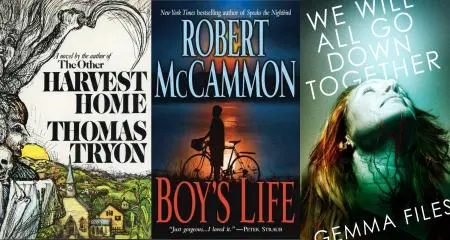

Over the decades, several writers continued producing folk horror titles (though again, this term did not exist at the time). Dennis Wheatley's The Devil Rides Out (1934) involves urban dwellers traveling to the English countryside and encountering a Satanic cult; Shirley Jackson wrote "The Summer People," published in 1948 in her collection Come Along With Me, which alludes to sinister, small town forces surrounding a New York City couple who decide to stay on at their lake house after Labor Day. Pinner's Ritual appeared in 1967, as did Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby, which brought the occult terrors of the country right into the heart of Manhattan, though for his follow-up novel The Stepford Wives (1971), Levin did travel outwards, to the suburbs of Connecticut. In 1973—the same year The Wicker Man appeared—Thomas Tryon published Harvest Home, a quintessential title in the subgenre, featuring a plot eerily similar to Anthony Shaffer and Robin Hardy's film, though different enough to pack its own wallop (even if its legacy as a horror classic isn't as secure as its English cousin).

The "horror boom" of the late '70s and 1980s produced numerous folk horror novels and short stories. Notable entries include: Stephen King's "Children Of The Corn" (1977), Michael McDowell's The Elementals (1981), Clive Barker's "In The Hills, In The Cities" (1984), T.E.D. Klein's The Ceremonies (1984), Raymond E. Feist's Faerie Tale (1988), and Ramsey Campbell's Ancient Images (1989), among others. The trend continued on into the '90s, most notably with Thomas Ligotti's clown-cult-themed "The Last Feast Of Harlequin" (1990) and Robert McCammon's much-lauded Boy's Life (1991), considered by many to be a masterpiece. By the end of the millennium, however, titles began to taper off.

It would be roughly a decade before interest in folk horror took off again, with Mark Gatiss's A History Of Horror no doubt playing a role in the subgenre's resurgence. The wealth of books and tales emerging in the last ten years simultaneously embrace and subvert the tenets of folk horror. Highlights include Adam Nevill's The Ritual (2011), Andrew Michael Hurley's The Loney (2014), and Gemma Files's We Will All Go Down Together (2014), all of which are highlighted in George Cotronis's aforementioned LitReactor column, as well as Elizabeth Hand's Wylding Hall (2015), Allison Littlewood's The Little People (2016), John Langan's The Fisherman (2016), Victor Lavalle's The Changeling (2017), and Dale Bailey's In The Night Wood (2018), to name only a handful.

With Midsommar this year and no doubt more films and novels on the horizon, it will be interesting to see what new backroads folk horror will take, and what new nightmares it will reveal.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com