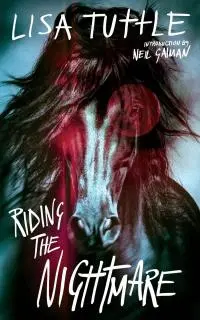

In his introduction to what can best be described as a “greatest hits” collection of Lisa Tuttle’s decades-worth of fictional output, Neil Gaiman notes that the twelve tales occupying Riding the Nightmare are nearly all, in some way or another, concerned with sex and death. These are, in Y.B. Yeats’s view, the only two subjects with which an author can and should concern themselves. Tuttle, according to Gaiman, kept a quote from Yeats on this matter tacked to the wall above her desk, alongside a similar sentiment from James Fenton: “Every fear is a desire. Every desire is fear.”

Sex and death, which as many have observed before, are more closely related than perhaps most would like to admit. Consider of course the French term for an orgasm, la petite mort, or “the little death.” It’s the idea expressed by Fenton above, that pleasure and mortality — fear and desire — are in fact one and the same, that to experience physical ecstasy is the same as dying, or of losing yourself and your senses to coital reverie, even if only a little.

Tuttle consistently finds herself intertwining sex and death throughout Riding the Nightmare. Or if not death, eerie terror. As Gaiman writes, “...Tuttle is able to tell impossible stories which evoke dread and strangeness and the uncanny, stories that feel right while being resistant to any explanation.” The author, in other words, takes her readers to exactly the kind of airy, unreal headspace that la petite mort indicates — a realm just touching upon that of eternal rest, but not quite.

The title story leads the collection, and as a representative for the remaining tales to come, it perfectly introduces the reader to Tuttle’s expert union of euphoria and fright. It’s about a woman named Tess who is dating a man in an open marriage. This arrangement suits her perfectly, because she insists she only wants the sex and mild, intermittent companionship that a committed married man can provide. However, Tess finds her ideal set-up threatened when the man’s wife becomes pregnant and he decides to fully devote himself to his new familial duties. As a result, Tess re-experiences a dream she hadn’t really thought about since childhood, in which a white mare comes to her window and takes her for a ride in the night sky. Given the name of this story, however, it’s no surprise there is little whimsy or fancy here: it is no dream, but rather a nightmare, and the mare is in fact a manifestation of Tess’s own fears and desires, with a sinister agenda of its own.

“Bits and Pieces” follows “Riding the Nightmare,” and it features a thoroughly gripping first sentence: “On the morning after Ralph left her Fay found a foot in her bed.” The story only grows weirder from there, as the main character finds a second foot under the bed; she realizes they belong to Ralph, yet also not, because she knows him not to be literally footless. They are, like the mare in the previous tale, manifestations of Fay’s grief over the loss of this relationship, the psychic remnants always left behind by former lovers, made impossibly tangible. Tuttle of course leans in to the impossible here, exploring what happens to a particular person’s mind when more body parts of former lovers begin to show up around Fay’s home. She becomes a kind of Dr. Frankenstein, piecing together the perfect man to occupy her bed while heading down darker and darker mental pathways.

Perhaps the most fascinating (and perhaps even most challenging) entry in this collection is “The Wound,” an earlier work written when, according to Gaiman, Tuttle was more of a science fiction author, a story existing “in a world in which sex and gender are fluid in ways that even Ursula Le Guin did not anticipate,” a world that “allows one thing to change, to allow us to see other things more clearly.” The narrative centers around Olin, a mild-mannered man who befriends a fellow school teacher, Seth. They attend operas together and take long walks along the river bank, and it soon becomes clear that the men are falling in love with each other. It is here the true themes of misogyny and homophobia emerge, as we learn that Olin will likely change into a biological woman to accommodate the burgeoning romance, a transformation somehow dictated by Seth. Olin’s students realize what is happening between the men and tease him, calling him “Miss.” Tuttle also reveals Olin’s ex-wife Dove was once a man named Leo, and her change was instigated by Olin. She tries to comfort him in his panic, telling him it isn’t so bad being a woman, even as Dove is in the process of changing back to Leo, reclaiming the masculinity lost long ago. It apparently is that bad being a woman in this world, just as it is in our world.

Perhaps the most fascinating (and perhaps even most challenging) entry in this collection is “The Wound,” an earlier work written when, according to Gaiman, Tuttle was more of a science fiction author, a story existing “in a world in which sex and gender are fluid in ways that even Ursula Le Guin did not anticipate,” a world that “allows one thing to change, to allow us to see other things more clearly.” The narrative centers around Olin, a mild-mannered man who befriends a fellow school teacher, Seth. They attend operas together and take long walks along the river bank, and it soon becomes clear that the men are falling in love with each other. It is here the true themes of misogyny and homophobia emerge, as we learn that Olin will likely change into a biological woman to accommodate the burgeoning romance, a transformation somehow dictated by Seth. Olin’s students realize what is happening between the men and tease him, calling him “Miss.” Tuttle also reveals Olin’s ex-wife Dove was once a man named Leo, and her change was instigated by Olin. She tries to comfort him in his panic, telling him it isn’t so bad being a woman, even as Dove is in the process of changing back to Leo, reclaiming the masculinity lost long ago. It apparently is that bad being a woman in this world, just as it is in our world.

Tuttle’s big finale is “The Dragon’s Bride,” a novella extended from a shorter piece first published in the 1980s. It’s a folk horror tale by way of Cat People — and that should be enough to pique a fount of interest without getting into the specifics of the tale, other than to say it is an incredible culmination of Tuttle’s primary theme throughout the collection, an ultimate statement on the dynamics of sex and death and how the two co-mingle. Moreover, to refer back to his introduction one last time, “The Dragon’s Bride” more than proves Gaiman’s assessment of Tuttle’s literary prowess:

Lisa Tuttle is...a killer with a handy boning knife, dangerous of eye and bleak of humour, and convincing enough in her depiction of reality and of human relationships to make her most improbable lies and her most pitiless plot twists feel both true and darkly inevitable.

If potential readers are unfamiliar, or even only slightly familiar, with Tuttle’s work and are curious to read more, Riding the Nightmare is an excellent launching point to familiarize oneself with her myriad talents.

Get Riding the Nightmare at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com