Triggering Content

The Babadook director Jennifer Kent's latest film, The Nightingale, has become one of the more controversial releases in the last year, with many labelling it yet another example of the highly problematic rape revenge fantasy subgenre, lumping it in with films like Lipstick (1976), I Spit On Your Grave (1978), Demented (1980), Ms. 45 (1981), Red Sonja (1985), Irréversible (2002), and Elle (2016), among others. If you're not familiar with these films, each basically follow the same format: a woman is brutalized sexually and physically, and sets about seeking vengeance against the men who raped her and, more often than not, left her for dead. Very often, too, the filmmakers behind such narratives attempt to draw a parallel between the monstrosity of the rapists and the "monstrous" ire of the victim, once she seeks retribution; in other words, her emasculation (often literal) and killing of these men is presented as equally immoral as the men themselves (most prominently seen in I Spit On Your Grave).

Of course, The Nightingale has very little to do with the above titles, one because it is Kent's intent to explore rape and violence from a more nuanced and sensitive lens (the subgenre is traditionally associated with exploitation and grindhouse films, in which the acts on screen are meant to shock and repulse without any designs on a conversation about said acts). Two, Kent takes great pains to avoid any possibility of objectification by shooting the two graphic assaults committed against her protagonist Clare (Aisling Franciosi) in close-up, forcing audiences to look at her pained face rather than her body.

Objectification and the "male gaze" (a term coined by feminist critic Laura Mulvey) runs rampant in the rape revenge film. Bloody-Disgusting writer Mary Beth McAndrews states that the "male gaze is used to eroticize the female body on screen and make her a spectacle to be watched and figuratively consumed," and that "the rape-revenge genre utilizes the male gaze to objectify the female body during and after her rape, playing up the trope of transformation into a spectacle of violence and sex." In other words, no matter how repugnant, there is a kind of lurid sexualization of rape inherent to these films.

It shouldn't come as a surprise that all of the titles mentioned above, and most others, were written and directed by men. Given this, it's hard to imagine this subgenre necessarily had women in mind—in other words, that these are stories designed to appeal to women, to address the horrors they experience and the rage they feel. And yet, several feminist critics and even audience members find these films therapeutic because they offer a fantasy that is both visceral and cathartic, a way of vicariously processing horror and rage in spite of the persistent eroticization of the protagonists.

Perhaps it is also to spite this eroticization that women writers and directors have begun to reclaim the subgenre for themselves, as Kent did with The Nightingale, voiding her narrative of exploitation and presenting rape and violence without sexualization. Other filmmakers, however, embrace the more exploitative aspects of the subgenre while still crafting stories that tackle the experiences of women. One of the earliest examples of this "new wave" of rape revenge films is American Mary (2012), written and directed by Jen and Sylvia Soska, and starring Katherine Isabelle in the title role. Like The Nightingale, this film explores the psychological ramifications not only of revenge, but of the larger brutal society that fosters patriarchal domination, rape culture, and even the concept of revenge or "eye for an eye" justice, with the climax and denouement seeming to suggest there isn't any justice at all, given that men are inherently more violent and unpredictable than women. The film both relishes in Mary's vengeful acts and questions whether or not said acts are necessarily good for her mental and emotional stability—especially since Mary only deals with the trauma of her rape externally, through physical action, and never internally.

Perhaps it is also to spite this eroticization that women writers and directors have begun to reclaim the subgenre for themselves, as Kent did with The Nightingale, voiding her narrative of exploitation and presenting rape and violence without sexualization. Other filmmakers, however, embrace the more exploitative aspects of the subgenre while still crafting stories that tackle the experiences of women. One of the earliest examples of this "new wave" of rape revenge films is American Mary (2012), written and directed by Jen and Sylvia Soska, and starring Katherine Isabelle in the title role. Like The Nightingale, this film explores the psychological ramifications not only of revenge, but of the larger brutal society that fosters patriarchal domination, rape culture, and even the concept of revenge or "eye for an eye" justice, with the climax and denouement seeming to suggest there isn't any justice at all, given that men are inherently more violent and unpredictable than women. The film both relishes in Mary's vengeful acts and questions whether or not said acts are necessarily good for her mental and emotional stability—especially since Mary only deals with the trauma of her rape externally, through physical action, and never internally.

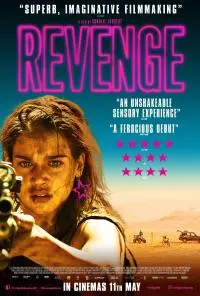

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Revenge (2017), written and directed by Coralie Fargeat. In this film, there is no mental deterioration of the protagonist Jen (Matilda Lutz), no commentary on the psychological ramifications of violence. The poster for this film features the title emblazoned in hot pink neon letters, juxtaposed with images of Jen, bloodied, dirtied, and aiming a gun directly at the viewer. This marketing, and the film itself, makes Fargeat's intent clear: this is pure escapism, and we are to cheer Jen on as she kills off her attackers, one by one. Furthermore, Jen literally becomes an avenging angel risen from the dead, a phoenix born from the ashes of her former self. Yes, her rape changes her from an aspiring starlet to badass survivor, and yes, there is no careful examination of trauma and rape culture, but that's exactly the point. The men in Revenge are awful, and they deserve every bit of violence coming to them; in this kill or be killed environment, Jen kills, and she is all the better for it.

While this film and American Mary are quite different, they do share one thing in common: they refuse to show their respective rapes in gratuitous detail. In Mary, much like in The Nightingale, the Soska sisters focus on their victim's face, rather than the act itself, the actions of the man; there is no nudity, and the scene cuts away before the act is over. Revenge refuses to show Jen's rape at all, as the lead up to the assault is upsetting enough on its own. This contrasts a film like Meir Zarchi's I Spit On Your Grave, with its infamous half-hour rape scene and tendency to eroticize its main character Jennifer (Camille Keaton). Mary Beth McAndrews breaks down this eroticization in her aforementioned Bloody-Disgusting article:

At the film’s beginning, Jennifer’s body is the focus of a man pumping gas; as he looks up and down her body, the camera mimics his gaze as it slowly pans up from her feet to her butt to her chest, painting a picture of male desire. Dressed modestly, she talks to him politely about her stay as he gazes at her body, foreshadowing horrifying acts to come. After her rape, this modest outfit is replaced with a sheer white dress that clings to her body and reveals her nipples and legs; her body continues to be eroticized and is viewed as such even though she has just endured a horrific assault. Even in moments of violence, Jennifer is meant to be viewed as a sexual figure, which is underscored by her use of sexuality to enact her revenge.

By eschewing both male-gaze-driven depictions of rape and eroticization in their films, Kent, the Soska sisters, Fargeat, and many other filmmakers create stories that, effectively, invite women to the table and let them in on the conversation. With these narratives, men are not the only targeted audience, thus establishing a new model for the rape revenge fantasy, one that perfects the subgenre rather than perpetuates its most problematic aspects. If these narratives need to be told—and it seems they do—they should be told this way.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com