Big Hollywood movies arrive in theaters with an entourage of tie-in merchandise at their heels, ready to lure you in with their enticing buy-ability. Aside from action figures, apparel and the endless other products we expect each summer, studios partner with book publishers to produce one of the more intriguing film extension items out there: the novelization.

Novelizations continue to appear in conjunction with some of Hollywood's most notable releases year after year. Iron Man 3, Man of Steel, Star Trek: Into Darkness and The Lone Ranger, just to name a few, will all appear both in theaters and on bookshelves in the coming months. You could argue these texts are mere cash grabs employed by the big wigs, just another way to take your hard-earned money. By and large, this is true: they'll keep producing novelizations if we keep buying them. But that's the key—we keep buying them, padding the pockets of studios and publishers enough to prevent the novelization's extinction.

For those of you in the dark, a novelization is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a transformation of a movie into a book, whereby the original narrative is delivered to audiences not through images, sounds and special effects, but through prose—or, the exact opposite of a novel's adaptation to the big screen. If you've never come across one of these literary oddities, that's understandable. While once a fairly popular medium, the novelization has lost some of its sway over the average consumer. Not only this, numerous articles about novelizations—from Slate to the Guardian, the New York Times and this piece by film critic Deborah Allison, amongst others—speak to the mediocre writing seemingly inherent to the medium, a byproduct of tight deadlines (most are written in four to six weeks) and, most likely, the author writing for money rather than love. Peter Kobel, author of the aforementioned New York Times article, says "these illegitimate offspring of movies and novels are often pulp fiction of the rawest sort. The literary equivalent of the action figures in fast food restaurants..." This is one of the nicer quotes about novelizations out there.

So what is it about novelizations that appeals to us? Why would anyone elect to read a book based on a movie, when there are countless original novels out there? Let's take a deeper look into this genre (and yes, it is a genre all its own) and see just how the novelization cemented its place in popular culture.

A Brief History

According to Deborah Allison, citing a book by Randall D. Larson called Films Into Books: An Analytical Bibliography of Film Novelizations, Movie and TV Tie-Ins, "'novelisations (sic) have existed almost as long as movies have' and can be found as far back as the 1920s, although it was not until the advent of mass-market paperbacks that they truly came into their own." I've yet to substantiate that bit about the 1920s with any other sources, and I've yet to get my hands on Larson's book, so for now I suppose we'll simply have to take Allison's word for it.

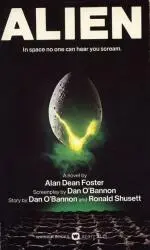

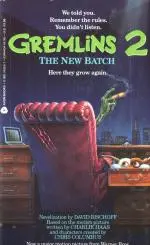

Peter Kobel states that novelizations had their heyday "in the '70s, [when] paperbacks based on popular movies like Jaws 2 and The Omen sold in the millions." Furthermore, franchise series like Star Wars and Star Trek (both largely penned by novelizer juggernaut Alan Dean Foster), Planet of the Apes, Indiana Jones, Superman, Batman, Gremlins, and James Bond faired well in the novelization market throughout the late '70s and '80s (and, in the case of Bond, created the paradox of novelizations based on films that were in turn based on pre-existing novels. If it was a blockbuster, a book tie-in was more or less a guarantee, though even smaller "cult" pictures like Enter the Dragon and Dawn of the Dead were novelized.

But why? What do these texts offer that their film parents can't? Well, it isn't so much about the films lacking certain qualities. These were the days before the VHS/VCR boom of the mid-to-late 1980s. Novelizations were a way to take that movie experience home with you, an opportunity to re-immerse yourself in its universe as many times as you wished, without having to wait until the film was either re-released in theaters or broadcast on television. The book was a memento, or a souvenir, reminding you of the summer you saw A New Hope for the first time.

So Why the Continued Popularity?

Obviously, the days of films as singular experiences in theaters and on television are over. Not only do movies get re-released all the freakin' time and broadcast round-the-clock on networks like TNT, AMC, HBO and Showtime, but home video is pretty much taken for granted—it furrows one's brow to learn I Heart Huckabees isn't available on Blu-Ray yet. And let's not forget on-demand streaming services like Netflix and Hulu, which pretty much ensure that, societally speaking, we'll never be without our beloved movies again.

And yet, novelizations still happen. I already mentioned this summer's blockbuster roster; last year saw books adapted from The Avengers, The Dark Knight Rises, and Brave. But hang on a minute—notice a pattern here? Including 2013's upcoming titles, these are all movies kids will likely see. Several adult titles were produced in 2012 and 2013 as well, notably Cabin in the Woods, The Lords of Salem and Resident Evil: Retribution, but while these are intended for seventeen-and-ups, they are films younger kids want to see, and likely sneak into the movies to do so, assuming their parents don't take them anyway. So again, it seems novelizations are targeted largely towards kids, those almighty arbiters of a tie-in product's success, those ultimate impulsive buyers.

But what about those kids who don't routinely do dangerous (aka fun) things like sneak into R-rated movies, or those that can't see a particular movie for other reasons? Remember Bart Simpson reading the Itchy and Scratchy Movie novelization because he was banned from seeing the film? Maybe not, but I think you see my point: book adaptations give certain filmgoers the chance to "see" a movie they might otherwise not get to experience. I'm living proof of this notion: my parents wouldn't rent Alien for me, so I read Alan Dean Foster's Alien instead. Ditto for Night of the Living Dead, a film that, unbeknownst to my parents, I had seen, but one I wanted to relive.

So That's the Answer? Novelizations are for Kids?

I think this desire to relive a narrative subverts the simple answer that novelizations are merely adolescent drivel, produced only because kids will buy it. Well, maybe that is the only motivating factor of studios and book publishers, but I still don't think "they're for kids" adequately addresses the novelization's popularity, since adults read them too. The thing is, reading a novelization isn't the same experience as re-watching a movie. You're experiencing pretty much the same narrative, told with a different voice, as well as descriptions that may alter your understanding of the original "text."

Novelizers, furthermore, often pad out their page/word requirements by getting into the characters' heads and revealing their thoughts. John A. Russo (who also co-wrote the screenplay with George Romero) did this with Night of the Living Dead, giving us glimpses of Ben's inner thoughts as he secures the farmhouse against the zombies. Or take this almost-free indirect discourse example from The Empire Strikes Back by Donald F. Glut:

The sight was horrifying. Vader, his back turned to Piett, was entirely clothed in black; but above his studded black neck band gleamed his naked head. Though the admiral tried to avert his eyes, morbid fascination forced him to look at that hairless, skull-like head. It was covered with a maze of thick scar tissue that twisted around against Vader's corpse-pale skin. The thought crossed Piett's mind that there might be a heavy price for viewing what no one else had seen.

That's the perspective of a relatively minor character in the film, and Glut captures his horror (and in turn, ours) pretty well, thus providing new context and understanding for the reader/viewer. Glut doesn't supersede the film, but rather gives it a nice companion.

Joe Queenan of the Guardian also theorizes that part of a novelization's appeal is its ability to make sense out of otherwise convoluted film narratives:

Novelisations, so it is rumoured, often contain supplementary material that make it easier to understand the film on which it is based. For example, the whole time I was watching Underworld: Rise of the Lycans, the third instalment in the Underworld series, I had a hard time figuring out why Lycans could sometimes get along quite nicely with werewolves, but at other times wanted to rip out their lungs and eat them. I was also confused as to why Lucian the Lycan could occasionally turn into a gigantic werewolf as if on cue, but other times had to lie there snivelling like a whipped cur while thrill-seeking lycanthropic flagellants shredded his naked flesh. Not until I read Underworld: Rise of the Lycans - The Novelisation, by Greg Cox, did it all became clear.

Film critic Deborah Allison brings up another good point in her essay "Film/Print: Novelisations and Capricorn One":

It is not unusual for such a book to adapt an older version of the script than the one that was actually shot, thus rendering a single definitive script source elusive if not downright illusory. It is fairly common to find whole scenes missing from the book or conversely to read extensive narrative episodes that never made their way into the finished picture...Such largely unintentional differences can provide fascinating insights into the film’s production history, revealing other paths that the film might well have taken.

Of course, we live in an era of extended cuts, director's cuts, and bonus discs boasting hours of deleted/alternate scenes, but again, with novelizations these differences are worked into a singular narrative by an author other than the original filmmakers. Apart from cut or reworked scenes, the novelization's narrative provides a wholly different experience than that of the film, and if you're particularly in love with a movie, this can be quite thrilling.

So, Are There Any Stellar Novelizations?

This is a tricky question to answer. If you're repulsed by the tropes of pulp fiction—concise, non-flowery, and sometimes repetitive or unimaginative prose, then no, novelizations will forever be total trash to you. On the other hand, if you can see the charm of pulp—as I can—then it's simply a matter of choosing those examples that most effectively retell the film's story in a prose-based landscape.

This is a tricky question to answer. If you're repulsed by the tropes of pulp fiction—concise, non-flowery, and sometimes repetitive or unimaginative prose, then no, novelizations will forever be total trash to you. On the other hand, if you can see the charm of pulp—as I can—then it's simply a matter of choosing those examples that most effectively retell the film's story in a prose-based landscape.

Personally, I remember feeling just as terrified at Russo's Night of the Living Dead adaptation, though it's been years since I read it. That Alan Dean Foster adaptation of Alien was pretty terrifying too, and I had a lot of fun reading Batman, Gremlins 2 (featuring a chapter written by a gremlin!), and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. I haven't made it all the way through that aforementioned Empire Strikes Back novelization by Donald F. Glut, but from what I've read so far, I'm honestly enjoying it. Glut utilizes the right amount of evocative imagery and character introspection to carry the same basic plot into new territory. Peter Kobel cites Finding Forrester, Gladiator and The Crossing Guard, a novelization written by acclaimed playwright David Rabe, as particularly excellent examples. And let's not forget the award-winning novelization of Snakes on a Plane, penned by none other than LitReactor instructor Christa Faust. Her take on the 2006 B-movie starring Samuel L. Jackson received critical praise for delving into the extended backstories of characters otherwise presented as silent snake food, and for perfectly capturing the campy pulp tone better than the film on which her novel was based.

Put simply, if you're a snob, novelizations are inherently bad; however, if you can turn off your brain for a minute and have a good time, novelizations can be a lot of fun.

Final Thoughts

It seems on the whole novelizations are still produced for the explicit purpose of garnering more money for a particular franchise. As Kobel notes, these books are typically found in supermarkets, drugstores, and airports, breeding grounds for impulse buys. They're perfect reads for plane rides, road trips, or days at the beach. Though some examples have in fact superseded their source material, for the most part they're better viewed as companions to their film counterparts.

The ultimate question is, do they have a future in this day and age? Well, it seems to me they should have died out a long time ago, but they’re still around. Red-headed stepchildren, black sheep, poorly-written trash—call them what you like, they’re still part of the family. They’re the folly-ridden but ultimately innocuous cousin: not as successful as other members of the family, sometimes downright silly and stupid. But they don’t cause much trouble, and sometimes offer insights the other stars of the family can’t provide. I don’t see them going anywhere anytime soon.

Have a favorite novelization you'd like to share? Are they better/worse/the same as the original film? Are there any movies you'd like to see adapted into prose? Sound off in the comments below.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com