Welcome back to What Works & What Doesn't, an ongoing series about the craft of screenwriting. Thus far, we've looked at narrative structure via Robert McKee's story triangle concept and the films Chinatown (Archplot), Lost in Translation (Miniplot) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Antiplot). We also began a discussion on the basic tools of screenwriting, action and dialogue. We focused on the former last time by examining Alex Cox's scene descriptions in Repo Man. Now, let's dig into the latter with a film that features some of the best dialogue EVER written: Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright's infinitely entertaining Shaun of the Dead (or, for the purpose of brevity, SOTD).

If you'll recall, in last month's column, I quoted the aforementioned McKee in his book Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting as stating:

The best advice for writing film dialogue is don't. Never write a line of dialogue when you can create a visual expression. The first attack on every scene should be: How could I write this in a purely visual way and not have to resort to a single line of dialogue? Obey the Law of Diminishing Returns: The more dialogue you write, the less effect dialogue has.

For the most part, SOTD absolutely defies this rule. Take a look at the interactive screenplay, which you can download for free via Three Flavors Screenplay, an official Universal website featuring all three scripts in the "Cornetto Trilogy" (SOTD, Hot Fuzz and The World's End).

As you can see, while there are more action-heavy pages throughout the script, for the most part, Pegg and Wright tell their story with dialogue. And while writing a virtually dialogue-less film is possible, it is far more difficult than you might imagine, and overall most screenplays will lean toward dialogue over scene descriptions.

If this is the case, the question here is: what constitutes good dialogue, and bad dialogue? (Or, what works, and what doesn't, where dialogue is concerned?)

McKee offers a fairly solid answer to our query:

Screen dialogue...must have the swing of everyday talk but content well above normal.

First, screen dialogue requires compression and economy. Screen dialogue must say the maximum in the fewest possible words. Second, it must have direction. Each exchange of dialogue must turn the beats of the scene in one direction or another across the changing behavior, without repetition. Third, it should have purpose. Each line or exchange of dialogue executes a step in design that builds and arcs the scene around its Turning Point. All this precision, yet it must sound like talk, using an informal and natural vocabulary, complete with contractions, slang, even, if necessary, profanity.

Given that dialogue, like scene descriptions, must work toward "turning" the script (i.e., generating beats, the basic building block of any screenplay), the screenwriter needs to focus on present situations and future actions, rather than on exposition. This isn't to say that exposition can't work its way into dialogue—in fact, it is inevitable that it will—but rather it is how the writer handles said exposition.

Let's take a closer look at the dialogue in SOTD and how Pegg and Wright handle exposition, as well as their use of dialogue in general, and determine if there are any moments in their script that don't work as well as others.

What Works

A quick aside: the dialogue in SOTD is pure comedic poetry from start to finish, with jokes set-up early and punch-lined pages and pages later. Moreover, as far as structure goes, the film is a perfect example of Archplot and in many ways a perfect screenplay. I could write at considerable length about every aspect of Penn and Wright's work, but I must reign myself in here.

Now, in addition to being a comedic "slice of fried gold," SOTD is also a fantastic late-stage Bildungsroman—the overall narrative arc is concerned with Shaun's maturity, his capacity to "sort his life out" and grow up. This arc is set up in the very first scene. Note how Pegg and Wright utilize slick, snappy dialogue to establish character relationships and reveal backstory while maintaining a sense of realism; put another way, notice that the dialogue here has a purpose—turning the scene toward a particular direction while also setting up Shaun's character arc—while appearing totally natural, just as McKee asserts dialogue should function.

LIZ

You shouldn't feel so responsible.SHAUN

Yeah...LIZ

I know he's your best friend but you do live with him.SHAUN

I know...LIZ

It's not that I don't like Ed.

(speaks off to her right)

Ed, it's not that I don't like you.ED

S'alright.We reveal ED right next to them, playing a horror themed FRUIT MACHINE which bleeps spooky electronic noises. He is in his late twenties and slightly overweight.

LIZ

It'd just be nice if we could-ED

(hits the fruit machine)

Fuck!LIZ

-spend a bit more time together-ED

Bollocks!LIZ

-just the two of us-ED

Cock it!

What do Pegg and Wright establish straight away with this scene? First, that Shaun and Liz are a couple, that Shaun and Ed are best friends, and that the latter relationship is taking its toll on the former—i.e., Ed is always hanging around, which, as you can see by Ed's few lines in this scene, can be a bit much to handle, to say the least.

Now, there are numerous ways the writers could have revealed this information, but I think they've chosen the correct path here, because the characters aren't just talking about the problem at hand, the problem is also happening in real time for the audience to witness (with Ed brilliantly interrupting Liz's dialogue with expletives, creating a collectively uncouth speech). Thus, Pegg and Wright utilize both dialogue and a visual expression to communicate an idea. Because of the comedic placement of sentences and the distinct absence of pointless words or sounds (uhs, ums, etc.), we of course know we're not witnessing a truly organic conversation, but because the sentences themselves aren't too stylized and feature McKee's "swing of everyday talk," the audience is able to suspend disbelief and get lost in the scene, absorbing from the very beginning the necessary information needed to follow along with Shaun's character arc.

Because, of course, as the interaction with Liz soon reveals, the problem really isn't with Ed specifically, but rather Shaun's inability to grow up. Ed is ultimately symbolic of Shaun's arrested development. Pegg and Wright take this theme further in the following scene, in which we see Shaun's home life with Ed and another friend, Pete.

PETE

I can't live like this. Look at the state of it. We're not students anymore.SHAUN

Pete-PETE

It's not like he even brings any real money into the house.SHAUN

He brings a bit.PETE

What, dealing drugs?SHAUN

Come on. He sells a bit of weed every now and again. You've sold puff.PETE

Once! At college! To you! Anyway, I did a lot of stupid things at college Shaun. I dressed up as Frank N. Furter, I drank snakebite and black, I slept with a fat girl. Doesn't mean I want to do any of them for a living.SHAUN

Look, I've known him since primary school. I like having him around. He's a laugh.PETE

What, because he can impersonate an orangutan? Fuck-a-doodle-doo.SHAUN

What?PETE

He's dead weight Shaun.SHAUN

Oh leave him alone.PETE

Okay, I admit, he can be pretty funny on occasion. I had a great time that night we sat up drinking Apple Schnapps and playing Tekken 2.SHAUN

Yeah, when was that?PETE

Five years ago. When is he going home?

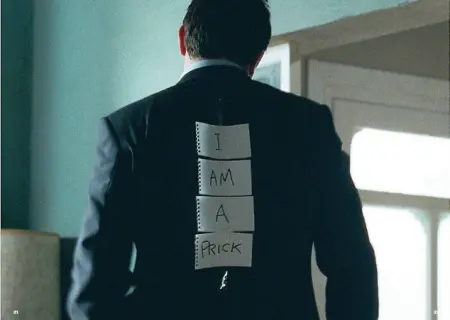

Once again, Pegg and Wright manage to give us a wealth of information about our characters' history through a naturalistic exchange. We learn (and, of course, see) that Ed is a slob, that he's living pretty much on the dole in this house with Shaun and Pete (minus his occasional weed sale), that the three have known each other since college, but Shaun has known Ed since they were boys, and, perhaps most importantly, Pete is a straight-laced, heteronormative prick (a fact Ed knows well).

So, what began as a triangle, with Shaun, Liz and Ed at its points has turned into something much more complex. In staying as close to Ed as he has, Shaun has basically clung to the carefree life he once had, a life of partying, video games and little responsibilities, represented by his boyhood friend Ed. The zombie outbreak serves a "hero's call to adventure" that challenges both Shaun's old life and future life.

However, as we learn by the movie's end, his old life isn't something to be scrapped completely, but rather lived in moderate doses. In other words, Shaun shouldn't become like Pete, a totally career-focused "adult" (prick), nor should he live like Ed either (a perpetual college boy). His actualization lies in the middle, a balance between the two extremes: happy and settled with Liz as his main-course life, and a slice of video games with Zombie Ed on the side.

What Doesn't Work

If you were hoping I'd have some evidence of SOTD's shortcomings, I'm going to have to disappoint you here. This script is flawless, and not only where dialogue is concerned. Basically, everything you need to know about the craft of screenwriting is contained within Pegg and Wright's script. As I stated above, I could write so much more about SOTD's brilliance, but there's just not enough time here. Even if you're not an aspiring screenwriter, I suggest picking it up—even prose writers can learn a lot about plot structure, character arcs, comedic timing, and of course, dialogue. A truly brilliant piece of writing all around.

What are some of your favorite examples of dialogue in Shaun of the Dead? Do you disagree with me and think there are lines that fall short? Any other films with great dialogue you'd like to shout out? Let us know what you think in the comments section below.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com