Welcome back to What Works & What Doesn't. In previous installments we've looked at the basic building blocks of a screenplay, working our way up from beats to scenes, from scenes to sequences, and sequences to acts. Now it's time to examine the screenplay in its entirety, from beginning to middle to end, Acts I-III. And to do this, we'll dig into what is considered a classic anti-war picture, Full Metal Jacket (for the sake of brevity heretofore referred to as FMJ), based on the novel The Short Timers by Gustav Hasford, written for the screen by Michael Herr and Stanley Kubrick, and, of course, directed by Kubrick.

The film's status as a classic is not undue. Overall, it delivers the "war is hell" message with a punch to the gut, a slap to the face, and a barrage of masterfully-executed hatred not unlike the infamous drill sergeant within the film, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). There are moments of sheer absurdity as well, the blackest of humor to demonstrate how even moments of levity in this hellish landscape are charred and singed, "unclean" or "impure" in some way. From start to finish, it is a solid piece of filmmaking and an engaging narrative; the actors deliver wonderful performances, the realistic and imposing sets equally terrify and awe, and the score grumbles and shrieks in equal measure. Kubrick definitely brought his A-game to the making of FMJ.

There's just one problem: The first half of the film, which examines the verbal and physical abuse, as well as the systemic dehumanization process of boot camp, is so much stronger than the latter half, which deals directly with soldiers on the field, following their initial lessons in humanity-stripping. This makes the actual scenes of combat in Vietnam far less memorable than scenes taking place on Parris Island, South Carolina at the U.S. Marine Corp Training Camp.

Put another way, the first half of the film works better than the second.

Let's get the ball rolling on this and sleuth out why.

The Completed Screenplay

If you'll recall in previous installments, we've looked to Robert McKee's Story to better define the mechanics necessary for effective beats, scenes, sequences, and acts. All these building blocks should be used to create "Story Events." Here's how McKee defines this term:

A Story Event creates meaningful change in the life situation of a character that is expressed and experienced in terms of value and ACHIEVED THROUGH CONFLICT.

So, beats lead to scenes, and scenes lead to sequences, and sequences lead to acts, with the acts finally comprising a Story. Here's what McKee has to say about this penultimate structure, forged from the basic building blocks (and, fittingly, the title of his book):

Story

A series of acts builds the largest structure of all: the Story. A story is simply one huge master event. When you look at the value-charged situation in the life of the character at the beginning of the story, then compare it to the value-charge at the end of the story, you should see the arc of the film, the great sweep of change that takes life from condition at the opening to a changed condition at the end. This final condition, this end change, must be absolute and irreversible.

I'd like to repeat a phrase from the above passage:

A story is simply one huge master event.

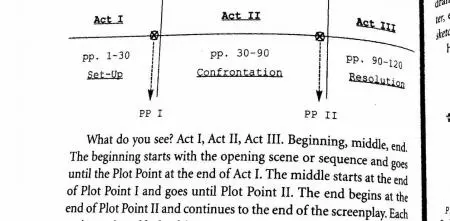

We can see a similar line of thinking in Syd Field's book on the craft, Screenplay. Here's a screenshot from the page in question:

Note the text below Field's diagram. The passage that is cut-off reads:

Each act is a unit, or block, of dramatic action, held together with the dramatic context: Set-up, Confrontation, Resolution.

In other words, while Act I, for instance, comprises the Set-Up of the entire screenplay, its movement is dictated by the same structure as the screenplay: Set-up, Confrontation, Resolution. In this way, we can consider each act of a screenplay its own mini-narrative—one designed, to be sure, to raise more questions and either set up the proceeding acts or, in the case of Act III, to resolve the overarching narrative and end the film—but a mini-narrative in its own right none-the-less.

What Works

FMJ falls in line both with McKee's and Field's parameters of a well-made screenplay, though it's essentially two movies smashed into one—almost, in a way, one film, and then its sequel, made by the same writers and director as the previous installment, but certainly its own animal, able to stand on its own two legs.

Because of this, each segment of FMJ—which I'll refer to as Boot Camp and War, respectively—contains individual story arcs, individual structures of Set-Up, Confrontation, and Resolution. The only connectivity between the two narratives is Joker (Matthew Modine) and, to a lesser degree, Cowboy (Arliss Howard), who both appear in the Boot Camp and War segments of the film. The former is identifiable as the protagonist of FMJ as a whole, and certainly of the War segment, though he is not the protagonist of Boot Camp. He is an important character in that narrative, to be sure, but our primary focus is on Private Pyle (Vincent D'Onofrio) who suffers worst of all at the hands of the company's aforementioned sadistic insult-smith Hartman.

Boot Camp is a study in the dehumanization Marines-in-training endure, the tearing down and rebuilding process encapsulated first by Hartman in one of his first speeches:

If you ladies leave my island, if you survive recruit training, you will be a weapon. You will be a minister of death praying for war. But until that day you are pukes. You are the lowest form of life on Earth. You are not even human fucking beings.

And later by Joker in voice-over narration:

The Marine Corps does not want robots. The Marine Corps wants Killers. The Marine Corps wants to build indestructible men, men without fear.

This dehumanization, this construction of men without fear, plays out later for Joker in War, but in Boot Camp, we're focused instead on what this process does to Pyle, who is probably of a significantly lower IQ than the rest of his company, possibly even bordering on mental retardation. He simply cannot "hack it," as the other boys say, in reference to Pyle's ability to grasp the fundamentals of Hartman's regimen and of the Corps at large.

In his first exchange with the drill sergeant, Pyle cannot stop smiling, not because he thinks Hartman's words are funny, but because his face just seems to be permanently set that way, in a slight grin (that is, of course, until Hartman beats the grin off his face). We consistently see Pyle fail at every obstacle, and it is overall made painfully clear that this boy shouldn't be here, that he isn't cut out for a life in the military whatsoever (it's never stated outright, but one gets the sense Pyle was drafted). At one point, we even see Joker attempting to show Pyle the proper way to lace his boots, like a father teaching his young son—for me, one of the saddest moments in the entire Boot Camp sequence.

Pyle tries his best, and even becomes quite adept at shooting his rife, named "Charlene" at Hartman's instruction. Despite this, however, Pyle continues to fail, and Hartman eventually begins punishing the company instead of Pyle, making them do pushups and squat-thrusts while Pyle stands by eating the jelly doughnut he pilfered from the mess hall or sucking his thumb while marching with his company. As such, the boys—Joker included, in a moment of weakness and frustration—beat Pyle in the middle of the night with soap bars wrapped in towels.

The ramifications of this act are far worse than any of them, especially Joker, could have imagined. As Pyle continues to excel at shooting his rifle, his sanity begins to deteriorate. He gains a "thousand yard stare," and seems to listen with a kind of rapturous distance—both inside himself and outside himself—as Hartman commends two former Marines for their stellar marksmanship and grace under pressure: Charles Whitman, who gunned down random, innocent people from the top of the University of Texas clock tower in Austin, TX, and Lee Harvey Oswald, whose actions need no description—examples of what a "motivated Marine and his rifle can do."

Pyle takes this lesson to heart, and on the night of the company's graduation, he steals away into the head with Charlene, locks and loads, and waits. Joker discovers him first, and then Hartman. As the latter revs up is particular brand of crude berating, Pyle shoots him straight through the heart, killing Hartman instantly. For a moment it seems like he might kill Joker too, but instead he sits down and kills himself.

It's a stygian and morose ending to the Boot Camp segment, but it makes its point loud and clear—this is what happens to a person when you dehumanize them, when you build Killers, "indestructible men, men without fear."

What Doesn't

War

This final lesson, for lack of a better term, plays out again in the War segment. For the sake of brevity, I won't go into as much detail here as I did with Boot Camp. To put it as succinctly as possible, Joker—despite his rebellious streak—suffers the same fate as Pyle, though his transformation into the fearless, indestructible killer is significantly more subtle.

Just as Hartman predicted, he becomes a "minister of death, praying for war"—he expresses such plainly in the barracks, bemoaning his boredom and wishing he could get out into "the shit." This despite the fact that, as a war journalist, he has seen and encountered things that clearly turn his stomach, that fill him with fear and desperation.

But Joker gets his wish, and gets assigned to follow a company into a the ravaged city of Hue, to document their victories. In the company is Cowboy from the Boot Camp segment, adding to the mix a sense of loyalty and camaraderie on Joker's part.

The men march into Hue, and one by one they begin to fall, killed by explosions, Vietcong booby traps, and finally by a rather adept sniper (hearkening echoes of Hartman praising Whitman and Oswald for their determination and marksmanship). Cowboy falls to the sniper's bullet, which elicits in Joker a sense of rage and vengeance. He storms the sniper's perch first, a burning, blackened, and labyrinthine building. He is nearly killed himself, but his pal Rafterman saves his life and riddles the sniper with bullets.

This gunfire does not, however, kill the sniper, and she begs for one of the men to shoot her, to end her misery. Joker finally steps up and, with his handgun, kills the woman, gaining in the process his "thousand yard stare"—one imagines he has not yet killed a person at such close range.

Following this, the men march on, singing, in unison, the Mickey Mouse club theme ad nauseam, their silhouettes faceless and without identity against a burning, Hell-orange landscape and, beyond that, total darkness. (The importance of this rather juvenile song and the overarching dichotomy of men and boys could fill a column in and of itself).

In voice over, Joker states:

I am so happy that I am alive, in one piece and short. I'm in a world of shit, yes...But I am alive. And I am not afraid.

See? Fearless, indestructible Killer.

What Is it Good For?

The War segment is magnificent storytelling, and filmmaking of a breathtaking genius. There is absolutely nothing wrong with it whatsoever.

The ultimate problem with War, however, is that Kubrick and company simply made Boot Camp too well. Yes, they are two separate narratives, intentionally designed to be disparate in some way, even down to their color schemes (Boot Camp is primarily blue and white, while War is often saturated in orange hues—juxtaposition of cool and warm, representing a descent into Hell). But while War is dependent upon Boot Camp to tell its story—as Field would note, its Set-up resides in the former segment—the same cannot be said in reverse.

Put simply, War needs Boot Camp, but Boot Camp doesn't necessarily need War. There are no outstanding questions left unanswered in Boot Camp, at least ones that have to be answered in order to satisfy the narrative arc. Moreover, War essentially makes the same narrative arc, just with a different character, which does not feel derivative, per se, but it is certainly less impactful the second time around. (I'll reverse most of this below however; stay tuned.)

I do remember, upon first viewing this film back in high school, hoping perversely that Joker wouldn't shoot the sniper, even though that's actually the humane thing to do, to put her out of her misery rather than letting her bleed to death, but knowing, in spite of this, that his doing so would equate to a loss of his rebelliousness, his "Joker" persona. So yes, this turn of events doesn't lack any emotional core, but it still seems somehow "lesser" than what we see transpire in Boot Camp. Joker's look of shock and horror as Pyle kills Hartman and then himself practically oozes a sense of self-loathing and guilt, a sense that Joker had as much a hand in creating this monster as Hartman and the others. For me, this single wash of horrific understanding is far meatier than the thousand yard stare Joker acquires at the end of War.

Absolutely Nothing?

No, Edwin Starr, I won't go that far. We can acknowledge that the War segment of Full Metal Jacket isn't as strong as its predecessor, Boot Camp, but that doesn't mean it isn't without its merit. I would never advise new viewers to simply watch Boot Camp and skip War, because despite what I said before, in some ways Boot Camp does need War, in the same way that one inevitably follows the other in real life as well as in this piece of fiction.

There is a question that arises at the end of the first segment: yes, one boy couldn't "hack it," and lost his mind before ever getting into "the shit," but what of the ones that can "hack it"? The ostensibly "normal" ones, the strong ones—what happens to them? It's a question that needs answering, and I do think Kubrick answers it well, even if his posing of the very question ended up being more memorable than the answer.

What say you, fellow LitReactor folk? Do you agree that War is a bit less impactful that Boot Camp? Do you think they're equally impactful? Or does War exceed the merits of Boot Camp, in your opinion? Let us know what you think in the comments section below.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com