If you haven't seen Making A Murderer yet, I'm sorry. This must be a confusing and annoying time to be online.

If you have, then you know it's a wild tale, or maybe even a wild tale INSIDE OF a wilder tale, all inside another wild tale. It's a Russian nesting doll of wild tales, but instead of a tiny little doll in the center, there's a white hot ball of outrage.

What is it about this story? Why has this, amongst so many others, caught so much attention? Why have so many of us stayed up so late to see its end?

How did storytelling take the legal troubles of Steve Avery and make them into an epic tale?

Quick Fill-In

If you haven't watched the series yet and plan to, this might not be the column for you. I'm going to avoid spoilers for the most part, but some aspects of the story have to be talked about.

If you haven't watched the series yet and don't plan to, let me bring you up to speed:

Making A Murderer is a ten-part documentary released all at once on Netflix. It follows the story of Steve Avery, a man falsely convicted of a rape in 1985. Avery was imprisoned for nearly 20 years until DNA evidence came into play and Avery was cleared of all charges. Once Avery was cleared, it became obvious that the Manitowoc County Sherriff's Department, the folks who put Avery behind bars, engaged in a sloppy investigation and even ignored evidence during the arrest and trial.

Steve Avery decided to sue Manitowoc County for damages. On the eve of Steve Avery's lawsuit, which had a strong chance of costing the county millions, a young woman went missing. Fast-forward, the young woman was murdered, and it looked like Steve Avery was the prime suspect.

The majority of Making A Murderer focuses on the second trial of Steve Avery in addition to another trial, that of Brendan Dassey, Avery's nephew, who may or may not have been involved in the murder as well.

The Storytelling Of A Documentary

Of course, there are those who would say that a documentary doesn't involve storytelling. Those who feel it's about being in the right place at the right time. You point the camera at what's happening and push the big red button.

Anyone who says that has not seen enough documentaries. Or hasn't seen enough crappy ones. Trust me, when you see one where people just pointed a camera at a thing, you can tell. Check in with what Kirk Cameron's doing these days if you don't believe me.

The way things are ordered. What's left in and what isn't. The way things are shaped. All of this puts documentary filmmaking firmly in the realm of storytelling.

And with Making A Murderer, if things feel very natural, it's because the filmmakers, Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi, did a great job.

If it feels effortless to watch, it's because of good storytelling.

Format And The Complicit Viewer

Making A Murderer's format, the multi-part series released all at once on Netflix, meant that viewers could choose how quickly they watched. At about 10 hours of runtime, Making A Murderer skirts the border between something you can plow through in a sitting and something that takes a little longer. It's one of those time machine shows. You come home Friday, you tell yourself you'll watch one, maybe two episodes, and then pow, you're at work on Monday, still in disbelief that you watched this entire drama unfold over the course of three days, and you're unsure if you changed your underpants the entire weekend.

It's the classic Netflix story. Especially the underpants part. But in this case, the binge-watch serves another purpose beyond making you the office stinky person.

Binge-ability means the viewer becomes complicit through the act of watching.

Making A Murderer is not light stuff. It's murder. It's real life. And you, the viewer, have to struggle with how much you're enjoying the high drama that comes with real peoples' lives and deaths.

It's different from a one-off documentary because, no matter how salacious the documentary might be, you probably won't watch it for ten hours.

It's different from a crime procedural show because, well, it's all real.

Choosing to present this story binge format means that the viewer has to wrestle with the fact that she's being entertained by something horrific, and that the horror is real.

I'm going to put this out there, a quote from the brother of Hae Min Lee, the victim whose murder provided the material for the the podcast Serial's first season. Lee's brother posted this on Reddit:

...I won't be answering any questions because... TO ME IT'S REAL LIFE. To you listeners, its another murder mystery, crime drama, another episode of CSI. You weren't there to see your mom crying every night, having a heart attack when she got the news that the body was found, and going to court almost every day for a year seeing your mom weeping, crying and fainting. You don't know what we went through. Especially to those who are demanding our family respond and having a meetup... you guys are disgusting. Shame on you. I pray that you don't have to go through what we went through and have your story blasted to 5mil listeners.

Forcing the viewer to play a part is good storytelling.

Good Editing Is Good Storytelling

I'm not going to lie. Part of what prompted this column was that I went for jury duty a couple weeks ago. And goddamn, that's boring.

It's a civic duty and all that, but boy is it a bore-fest. It's like the worst parts of the DMV and airport security rolled into one. You show up early. You go through the metal detector. You watch a video about how important it is to show up for jury duty AFTER YOU'VE ALREADY SHOWED UP. The woman behind you is texting on an old-school phone, and every time she presses a button, the phone makes loud tones. Do you know how many tones it takes to send a text? Four billion.

While I sat there, I thought about how interesting Making A Murderer was, and I thought that the filmmakers must have done A LOT of work to chop things down to a reasonable, tasty size. Because if I sat around for about 5 hours without even being on a jury, there must have been a whole lot of sitting in boring rooms going on in a big-time murder trial.

Indeed, the filmmakers cut a lot. 700 hours of footage cropped to about 10. That's an end product that comes out to about 1% of the original footage.

I've made this argument before, and boy did I catch some hell, but I'll always pose that good editing is good storytelling. When you can look at a mountain of content and cut it down, kill so many of your babies, then you're forcing yourself to only use the absolute best, most crucial material. And when we're talking about something as complex as the stories contained in Making A Murderer, that makes things ever tougher. Do you keep this story element, or do we keep this emotional footage? Lots of choices were made, and clearly lots of good ones.

Good editing is good storytelling.

Villains

Every story needs a villain, and no doubt, the biggest villain in this story was Ken Kratz.

It's not hard to nail down why viewers had such disdain for Kratz. He's on the wrong side of public opinion here, he blatantly exploits goodwill towards law enforcement, and his salacious texts rank up there with Warren G. Harding's erotic love notes when it comes to politicians crossing a line.

In fact, let's play a game: Harding or Kratz!

See if you can guess which quotes were from letters written by former President Warren G. Harding and which were from former District Attorney Ken Kratz

Thanks for putting up with me so far. I wish you weren't one of this offices clients. You'd be a cool person to know!

I need direction from you. Yes, you are a risk taker and you can keep your mouth shut and you think this is fun...or you think a man twice your age is creepy so stop.

I'm serious! I'm the atty. I have the $350,000 house. I have the 6-figure career. You may be the tall, young, hot nymph, but I am the prize! Start convincing.

My Darling, there are no words, at my command, sufficient to say the full extent of my love for you — a mad, tender, devoted, ardent, eager, passion-wild, jealous . . . hungry . . . love . . .

Sigh. Jerks just don't do torrid love affairs like they used to, do they?

Indeed, it's the documentary's reveal that Kratz was sending sexual texts to a victim of domestic abuse, a woman who he was supposed to be helping in his role as District Attorney, that really sealed the deal and positioned him as the true villain.

Up until the part about Kratz's texts, the only display of Kratz's true nature is the way in which he does his job. It's a struggle, but it's not out of line to watch him work, and to see that he's a tenacious D.A. who is pressing a conviction. He's doing his job, but there's something about him you just want to dislike.

With the reveal of his impropriety, and the reveal that the state of Wisconsin basically let it slide, the storytellers give us the true villain we wanted in Kratz.

Good storytelling has good villains.

It also doesn't hurt that the dude has a very Snidely Whiplash mustache.

Heroes

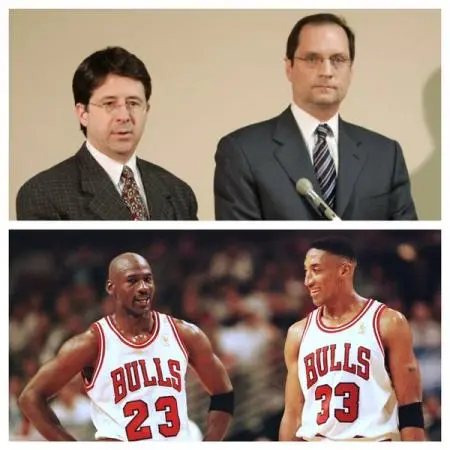

The story, no doubt, finds its heroes in Jerry Buting and Dean Strang, attorneys for the defense.

What's great about the way the heroes are introduced is the subtly. These two guys show up, another pair of dudes in plain suits who are poking around the case. But by the series' end, these guys are giving viewers the warm fuzzies.

The series does an incredible job of easing these characters in, letting them speak for themselves, and letting the audience fall in love with them. The series doesn't put in trumpets when they show up on scene. The series doesn't tell viewers, explicitly, that these are the good guys, and instead lets the good guys cement their own positions in our hearts through their actions. The old "show, don't tell" executed beautifully.

I don't want to belabor the point about whether or not people adore these men. I think I'll let the internet speak for itself on this one:

![]()

image

![]()

image

![]()

image

![]()

image

![]()

image

Heroes emerge on their own in good storytelling.

Good Use of Time

A hallmark of bad storytelling is that you have no idea how much time has elapsed. Is this taking place over the course of a day? A year?

Time is one of the secret weapons in Making A Murderer. We fast-forward through the past, then slow down in the present, and near the end of the series, speed up again.

The way in which time passes is very real and tangible, especially when, near the end, you see the time on Steve Avery's face. Oh, and Brendan Dassey's. We haven't talked about him much yet, but we will.

The documentary was so masterful in using time that, by the end, the flashing of dates at the bottom of the screen MEANT SOMETHING. I wouldn't normally see a date flashed on the bottom of the screen and feel something. Let's be honest. It's the only movie where, more than once, a date flashed on screen and I said, "No fucking way."

Time can work for or against a storyteller, and the storytellers in this case tamed time and made it do their work.

Good use of time is good storytelling.

Strong A and B Stories

The Steve Avery story is strong, and it's gotten a lot of attention, but it's my opinion that the B story, Brendan Dassey and his parallel murder trial, is even more heartbreaking.

With the Steve Avery story, we got something that made us think. You really do wonder if Avery was framed. You wonder what happened to the victim, Teresa Halbach.

With the Brendan Dassey story, we saw something truly, undeniably heartwrenching. A young, low-I.Q. boy is forced into a confession by police, and it's hard to watch the series without feeling like the kid is being railroaded. You watch when Brendan calls himself dumb over and over. You watch him talk about how he was self-conscious about being fat. You watch this kid talk about all these teenage things in front of the whole world.

What is sometimes forgotten with A and B stories is that they can be closely-related and still do different things. The A plot in Making A Murderer engages the mind, and the B plot punches you in the stomach. The way in which the two stories were presented as separate, distinct threads that intertwine, is strong storytelling technique and certainly part of what pulled viewers along.

Good balancing of A and B plots is good storytelling.

Timeliness

No doubt, this is a story for our time.

It's interesting to watch the way in which prosecutor Ken Kratz uses the unassailability of police officers as evidence throughout the case.

In 2005, when the case occurred, we were living in a different world. Certainly a small, 94% white community would have a strong reaction to the implication that police might be wrong in 2005.

But in 2015 and 2016, and in the wider world, feelings are different.

Police are no longer the perfect, always-honest folks we thought. Or at the very least, that status has come into question.

Anyone who has told a story at the wrong time knows how much timeliness counts. You have to wait for your moment. You don't, for instance, go on a date, and just before dinner arrives at the table, tell your date about the time the Dave Matthews tour bus dumped sewage off a bridge, drenching a boatload of sightseers in Chicago.

Good timing is good storytelling.

We Are Not Left With Answers

Making A Murderer is a twist on the mystery story. Rather than a whodunit, we have a whodidn'tdunit. This leaves the wild conjecture and internet sleuthing (aka "The Fun Parts) to the audience.

It's an interesting choice, shying away from making statements and putting forth suspects. But I think it's an important one.

The filmmakers were trying to make a good documentary, and they were also trying to get people talking about this strange, unfair, unjust case. It's my opinion that the way in which this story was told leaves a whole lot for everyone else to talk about.

The filmmakers said their piece, and now they're letting the world take it from here.

They wanted to make something great, and they wanted people to talk about it.

A story that accomplishes its goals is always the result of good storytelling.

What do you think? Did Making A Murderer work for you?

About the author

Peter Derk lives, writes, and works in Colorado. Buy him a drink and he'll talk books all day. Buy him two and he'll be happy to tell you about the horrors of being responsible for a public restroom.