If you haven't seen Mad Max: Fury Road yet, see Mad Max: Fury Road.

There's no reason to not see Fury Road. Not a single reason that I would tolerate. It might be too late to see it in first-run theaters, which means it's the perfect time for the cheap seats, where the only thing more stale than the popcorn is the concern for whether or not you're sneaking in tallboys.

Fury Road doesn't need me to tell you how awesome it is. How it's redefined the car chase. How its emphasis on practical effects has reminded us that, yes, we can tell the difference. Fury Road is the movie that dares to say, “Yes, you can name a character Slit.”

But what we might need, what some people might need, is a little bit of talk about just how well-written the movie is.

Indeed, if you looked at all the dialog on the page, you wouldn't find a lot. Mad Max: Fury Road is a movie that the director, George Miller, describes as "visual music," a movie he says can be understood by those who don’t speak English.

Fury Road might seem like it succeeded for reasons other than its writing.

I'm here to tell you that the writing was key. That good technique and innovation in the writing, those things were the keys to it all. Good writing is what has ensured that Fury Road is a movie that will ride eternal, shiny and chrome.

First Things First, Yes, There Was A Script

There's a rumor of sorts circulating that Fury Road was scriptless. Let's squash that.

There was a script. It was a different kind of script, a script that started as a graphic novel consisting of 3,500 storyboards. Which is what the actors and crew worked from most of the time.

From that, a screenplay, a more standard script was created.

Let's remember, the "writing" of a movie goes way beyond the words that come out of people's mouths.

If you want to argue whether a script can come in graphic novel format, go ahead and tweet Scott McCloud (@scottmccloud) about it, because he has a lot more interesting, convincing, curse-free things to say on that topic than I do.

'Fury Road' Was Always Meant To Be A Movie

Yeah, we're in the era of book-to-movie. We're in an era, maybe just coming out of it, where it would seem that selling a book is all about selling the movie. Write a book filled with characters that can be played by teens with swoopy hair and washboard abs, stretch it into a trilogy, and make it cinematic as hell. Boom.

It's been a good thing for some movies. But is it a good thing for books?

In a recent piece, Tom Spanbauer talked about his book The Man Who Fell In Love With the Moon and what happened when Ross Bell, Fight Club’s producer, tried to turn it into a movie. Bell said the book was the best book he’d ever read. He said the book was great, but he couldn't turn it into a screenplay. Bell said the book was, therefore, flawed.

What Bell sees as a flaw, I see a different way. A book that's meant to be a book, a story that's told in its intended medium, that's a beautiful thing. A book being "unfilmable" is hurtful to a writer's wallet, but that doesn't mean the material is flawed. It means it was created in the right medium.

Fury Road was written as a movie. It was always meant to be a movie. And that's why it works.

There's something to be said for writing your movie as a movie, your book as a book, your comic as a comic. There's something to be said for writing in a medium such that any other medium just won't work, using a medium to its maximum potential such that your art's translation to another medium means, necessarily, losing a piece of the story. There's a way in which an inability to translate means you've used a medium to its fullest.

'Fury Road' Was Edited Down To .4% Of Its Footage

In my first ever LitReactor class, a novel-writing class with Max Barry, I was kind of horrified when he told the story of editing his book Syrup. Barry said he kept a file of everything he cut. By the time the book was finished, the word count in the scrap heap dwarfed the word count of the final book.

That was bad enough. The truth that I might cut more than I'd keep, that was hard to hear as somebody trying to churn out a first draft.

If Max Barry had told me to George Miller my work, if he told me that my final draft would consist of .4% of my rough draft, I don't know that I could've survived it.

When George Miller shot Fury Road, he shot 450 hours of film. 450 hours. All of which was condensed into 2 hours of movie. That's .4% of the rough material that made it into the final cut. Not even half a percent.

73,404 is the number cited for words in The Catcher In The Rye, a fairly brief book. If you kept .4% of that book, you'd have 294 words. That's not a lot of room to talk luggage and bathroom graffiti, and you can just forget about solving the mystery of where ducks go in the winter.

It takes guts to cut that hard. It almost certainly means leaving out some very good, very worthwhile material.

Fury Road was edited hard, and the story works, the action works. Everything that needs to be there is. And nothing else.

Good editing is indicative of good writing technique.

Wait. Let me take a page from Miller's book and rephrase that.

Good editing is good writing.

Backstory Filled The World

Fury Road feels full. Not "full" as in "filled with stuff." Fury Road is “full" in that it takes place in a real world where people lived and will continue to live after this story ends.

Every vehicle, every character had a backstory.

For example, you can read an entire backstory on the MAN KAT I A1 (8x8) "Doof Wagon". Or you can read the backstory of the wagon's signature rider/player of flamethrower guitar, Coma Doof Warrior (oh, don't worry, we'll get to Coma Doof Warrior).

You can look up a brief backstory for Rictus Erectus. Which is worth doing if for no other reason than the opportunity to type "Rictus Erectus" into Google.

Everything had a backstory. A conceived, written backstory. Everything existed outside of the movie, outside of the two-hours we saw on screen. Everything in the movie was something before we saw it, and it felt like it would be something long after we turned to watch something else.

The world, everyone in it, it all felt like something real because, narratively, it was.

And the best part, all the backstory informed the movie, but it didn't drive the story.

A crappy movie, a badly-written movie, we'd get all this unnecessary backstory. Sometimes it feels like you watch a movie, and the screenwriter has something to prove. They want to show you how much work they did. They wrote a backstory for everything, and that needs to be on the screen. Fury Road left that stuff out. And for good reason.

All the back story filled the world with great stuff. And using that story sparingly meant we got to experience an actual adventure in this world as opposed to a history lesson about a fictional world. Great use of written backstory.

The Movie Lived In The Crazy

I have three words for you.

Coma. Doof. Warrior.

Yes, none other than the pajama-clad "little drummer boy" with the flamethrower guitar.

If you haven't seen Fury Road yet, if you didn't drop this column and get yourself a ticket, damn it, ask someone about the guitar dude. Ask one of your friends. If your friend doesn't know about the guitar guy either, good sign that it's time to drop him as a friend.

Doof is kind of an encapsulation that comes in handy when you're talking about Fury Road, when you want to talk about what makes it so crazy and what also makes it so awesome.

What we got from Doof, we got the idea that we were in a fantastic world that still follows our basic rules. No magic, no dragons, no outer space stuff. But insane cars, hyper-real characters and just enough filth to fill in any gaps.

Very often, when a story has a bizarre world, the entry point for viewers is through a character who is also new to the world. Think Charlie And The Chocolate Factory. Think The Wizard of Oz.

It's the fish out of water who guides us through the world, maybe the fish out of water on acid. It's tried and true, but damn, is that the only way to enter a strange world?

The weakness of the fish-out-of-water-as-guide method is, as a viewer, I have the strangeness normalized for me. Because I'm watching a character from my world enter this strange world, I know that what I'm seeing is supposed to be unusual. I know that this chocolate factory is an anomaly, not the norm.

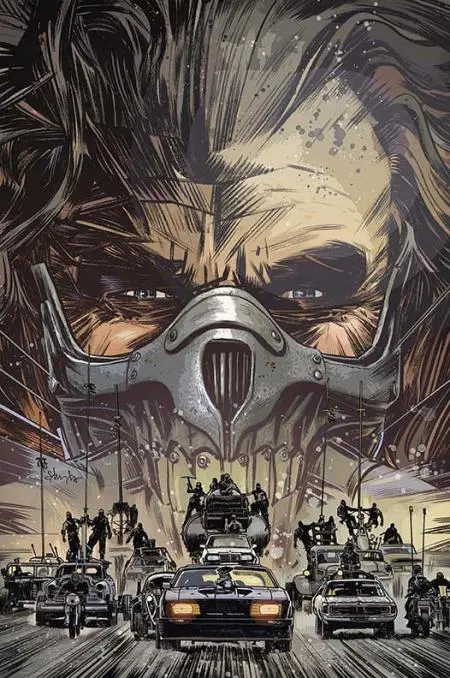

Fury Road presents us, unapologetically, with the weird.

All the characters buy into it. We didn't need someone to say, "Hey, what the fuck with the guitar guy in the pajamas?" We didn't need that because if the characters question the world, if they point out how weird it all is, then the audience is removed from the crazy. When you do that, when you have a character normalize something that way, you take away from the fantastic nature of something, the fantastic nature you're trying so hard to build. By leaving all of that out, by entering us into this world with a narrator who is part of the crazy, we got to live fully in Fury Road's crazy.

The Story Answered The Question: Why Live?

I am the one that runs both from the living and the dead. Hunted by scavengers, haunted by those I could not protect. So I exist in this wasteland, reduced to one instinct: survive.

Fury Road answered a question asked by a lot of other movies. A question that's been inadequately answered thus far.

How many people have told you they would kill themselves in a Walking Dead scenario? How many have read or watched one of the many, many stories of post-apocalypse and wondered, Why the hell does anyone even bother?

The characters in Fury Road live in a craphole. And I don't just mean Australia. (Note to Australian readers: I have an Australian co-worker that I REALLY need to burn every so often. I do not actually hate Australia, and I apologize for being physically incapable of writing this without slamming Australia one time.) The characters have terrible lives. You have the War Boys, diseased young men who won't live into middle age. You have the Vulvani, the women who live their days on motorcycles in the desert. You have the wives, who live in a prison that has some books, and that's pretty much the best thing you can say about their situation.

You have all this, you have a post-apocalyptic vision that's as bad, if not worse, than most others. And yet, there is a reason for each character to go on. There's a reason they continue. And it's not as simple as "Well, I have this family, so I guess I'll stay alive for them."

Their reasons are insane, they're selfish, and they're bizarre. They're foolish. And sometimes they are nothing more than mental illness. But they exist. A portion of the sparse dialog explains why the characters fight to live another terrible day, and it’s a portion well-spent.

George Miller Picked A Great Editor

George Miller hired his wife to edit Fury Road. She'd never edited an action movie before, which is precisely why he wanted her to do it. He wanted his movie to look like no other movie.

Margaret Sixel set upon the difficult task, and she proved that up to now, she may have been missing her calling.

Fury Road is edited in such a way that you're never confused about where you are in space. Even when you can't see, even when you're deep inside a sandstorm, even when you're blasting through a desert on a motorbike, the movie carries the viewer through what could be some really confusing sequences. It respects the space and the placement of things so well that it really, really makes you feel like you’re there.

And my god is this a welcome break from the frenetic action sequences that come in so many current films.

I unfairly blame the Bourne movies for this, for the way in which action is shot with so many quick cuts that it’s hard for a viewer to understand what's going on. It’s a technique that can work, that can make the pace feel quickened and make the viewer feel involved. But most times, most times I just feel lost, and then it doesn’t take long before I say to myself, “I’m just watching blurs on a screen right now.”

Oftentimes, action movies are cut together the way some choose to cut together a story about tripping on shrooms. "Yeah, it's confusing. Because I wanted you to FEEL what it's like to be on shrooms."

It's a personal pet peeve of mine. I like my stories to be stories. Have your experience, then relate your experience to me so I can understand it.

Fury Road does a beautiful job of relating what is an impossible experience, and it does so seamlessly.

It's a fine line, to put a story together in such a way that it makes sense, yet the viewer doesn’t feel the editor's breath on her neck the whole time, doesn’t feel a presence saying "I'm here. Let me show you where to look. Let me take care of all this." That’s beautiful editing.

Beasts In Repose

If you cannot imagine a monster in repose, it is a bad design.

-Guillermo Del Toro

Possibly one of the best scenes in the movie, the slowest scene in a movie that's nearly non-stop, comes when the bad guys are camped out, just sort of waiting around. They’re parked, all working on their own little rituals. Prayer, sleeping while suspended from a web of bungee cords, having giant, grotesque feet maintained. You know, evil desert warlord type of stuff.

The bad guys are grotesque and weird, and they take a break. By the Guillermo Del Toro rule, they work beautifully.

It's a difference between a movie like this and a horror movie. What the hell does Freddy do during the day? What does Jason do when he's not taking Manhattan? When the Leprechaun has all his gold in his possession, does he just hang out in his studio apartment all day, sliding coins under his front door and into the hallway in hopes that someone will pick one up and then the Leprechaun will be able to go outside and actually do something?

Fury Road’s bad guys are characters. And they’re characters because they can exist in states beyond angered action.

Intimacy

There was no way George could have explained what he could see in the sand.

A wild, personal vision is a risk. It can work, and when it works, it's great. When it doesn't work, it's a disaster of Birdemic proportions.

George Miller had a vision. He knew what he wanted to make. He knew what he wanted things to look like. He knew, when he made this movie, what he wanted.

Let's face it, you'll never get a Spider-Man movie like this. A movie that plays it fast and loose with a character. A movie that’s driven by a singular vision, a movie that even the actors are unsure about during filming.

If I can make one more plea to get you in a theater, if I can give you one more good reason to sit in front of a screen while Fury Road plays, let me try this.

Fury Road is the most intimate big-budget action movie I’ve ever seen.

I never thought I would describe this kind of movie this way. I never thought a movie with a robot arm and a post-apocalyptic world and an endless car chase would feel personal in any way.

Mad Max: Fury Road is a personal, intimate story, a rare instance where the greatness one person saw in his mind made it onto a screen. It doesn't read like a movie where a dozen of the same ol' people sat around and homogenized something great into something palatable.

Because so much work went into it, because George Miller put in the time and the energy and the effort, because of all the ways in which Fury Road is well-written, it manages to be that rare, beautiful confluence of individual voice and spectacle.

Plus, again, just one more time: Flamethrower Guitar.

About the author

Peter Derk lives, writes, and works in Colorado. Buy him a drink and he'll talk books all day. Buy him two and he'll be happy to tell you about the horrors of being responsible for a public restroom.