Original header image by KRIPPS_medien

I tend to be musically minded, often swapping in songs and lyrics in place of emotional revelation, and, even in music, it's important not just what you say, but how and when you say it.

In High Fidelity (both the 1995 novel by Nick Hornby and the 2000 film starring John Cusack), main character, Rob, lays down a series of rules of how to make a great mixtape. Roughly paraphrased, they are:

- Kick the mixtape off "with a killer."

- Then take it up a notch.

- [This is almost verbatim what John Cusack says in the film] But you don't want to blow your wad, so you have to cool it off a notch.

- Avoid doubling up on artists, unless you're doing a two-songs-per-artist thing.

The rules run through that weird middle ground between clear and frustratingly abstract, and the ability to make a good or great mixtape or mix CD is not incomparable to ordering the short stories in a collection.

Just to show my dusty-like age, I'm not talking YouTube or Spotify playlists here—you can swap out songs and artists with those platforms, but back in the day, when you committed to a track listing, you were stuck once the tape rolled or the computer slotted in those sequences of ones and zeroes. If you wanted to fix it, you had to make a whole new product.

Much like when your book goes to print.

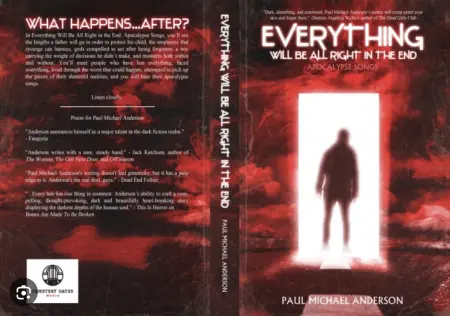

At this point, I've produced two collections: 2016's Bones Are Made To Be Broken, which LitReactor reviewed back when it did such things, and Everything Will Be All Right In the End: Apocalypse Songs (out now), the vast majority of which originally appeared in magazines and anthologies.

I'd also, once upon a time, been an editor and had to assemble tables of contents for anthologies and magazines. So I have a... fair? Let's say fair... understanding on how to do it in a way that turns out something compelling or interesting for the reader.

And, in a way, I followed the High Fidelity rules. Modified, they are:

- Don't include everything you've written.

- Start the book off with something that's either going to thematically or narratively punch the reader (or both).

- Avoid getting too same-y with the content, themes, tropes; space it out.

- Don't start with longer pieces if you can avoid it (see rule number one if you can't).

- The book should wrap with something that'll make the reader sit back after reading that last page (not counting story notes or author bios or whatever), and have to take a breath as they come back down to Earth.

Now, those rules assume two things: One, your collection is mostly composed of reprints from things you've sold elsewhere. Two, you're planning on the reader going straight through the book and not leap-frogging around.

On the first assumption—I know loads of writers who produce original collections with pieces solely for that book, and I'm not throwing shade on them, but I can never get behind that idea. For me, buying a collection is more of a leap of faith on the reader's part than buying a novel or novella because they have multiple opportunities to be let down or feel they've wasted their money. By having the pieces of my collection come from previously sold works, I can at least tell myself that the stories have "proven themselves" in the marketplace once before.

(And, yes, my collections do have original pieces; Bones had two, including the title novella, and Everything has three, but you get my point.)

On the second assumption... that's why you're here, gang. You're assuming a reader is going to go straight through the collection, from intro to story notes, in a linear fashion.

When I was getting the manuscript together for Bones Are Made To Be Broken, I spent weeks trying to figure out how it all fit together. I had, at that point in 2015/2016, published or sold 24 stories, and they were all over the map.

Not all of them made the cut. Bones has only 14 stories, so I left out ten others. Six of these left-out stories were zombie stories written at the very start of my career (when I—idiotically—thought there was a dearth of zombie fiction in 2010; stop laughing), two were flash pieces, and another two were just random things that were, particularly obviously in hindsight, me learning what the hell I was doing.

When I had selected the pieces, I then had to figure out the order. I went to my shelves, ultimately pulling Joe Hill's 20th Century Ghosts for inspiration, because, at the time his collection came out, no one knew who Hill was or what he was later going to do. The book starts with "Brand New Horror", a ridiculously confident tale about a cynical editor on the hunt for this transgressive horror story. It zips along, punching the reader in the face page after page. The second story, the title story, is worlds apart from it, and the reader has to mentally recalibrate themselves before continuing. Again, another confident move.

I used it as a template for Bones.

Bones Are Made To Be Broken starts with "Crawling Back To You", a vampire story where the villain and the familiar, our POV person, are in a toxic codependent relationship. It's violent and gory and starts with the line, "Patty pulled the .38 from the glove compartment when the radio, even jacked to maximum volume, failed to block out the waitress's screams."

Bang, zoom, right in the kisser, as they used to say back in my parents' day. Particularly effective when the second story, "Survivor's Debt" is about two old men, with one believing he's witnessing the mental collapse of his friend because his friend believes he's seeing ghosts from his past.

From there, I assembled Bones, following either theme or how one story ended and another started (I separated two stories which open with the main character holding a gun, for example). I knew, and had conversations with my editor over it, I wanted to keep the title novella towards the end because it literally took a quarter of the book's page count.

I also knew that I was going to end with "All That You Leave Behind," not because it was the most recent piece, but because, after starting my first book with a vampire's familiar getting annoyed at a victim's screaming, I wanted to end on an emotional story about a couple coming to terms with their missed chances and bad luck. The book ends with the line, "They faded, faded, and, by the time they reached the corner, they were gone."

It might've meant nothing to the reader, but it meant everything to me.

Bones Are Made To Be Broken was a difficult book to put together, if only because, in all the included pieces, I was very, very clearly learning the ropes, so I was all over the place, only really starting to get the hang of it in those last two years. And I must've done something right—the title novella got juried onto prelim ballots, best-of editors said nice things about it, and I still make royalties on the book, which is most important of all because that means people are still reading it. Not bad, for a nobody.

Everything Will Be All Right In the End, the new book (and why I'm writing this article!), was a completely different situation. For one, I had fewer pieces to choose from—not necessarily because I was writing less (I wrote two novels and three novellas in the six year period between Bones and Everything, on top of the stories), but because the stories were written to-order, often at the request of editors who'd reached out.

Also, the stories were different. The things I was testing in Bones came into their own during the Everything period. I was also, obviously, a different person, in different circumstances, and whereas Bones came together after a writer and an editor chatted at-length, Everything was literally put together because I saw an opening for short story collections from a publisher and, when I checked, I realized I had enough pieces for a new book.

For the second book, I found myself not looking to Joe Hill, but to Harlan Ellison's work, particularly in the 1970s. Although Shatterday and Strange Wine come to mind when thinking of Harlan, it was more about how each book seemed like a milestone in Harlan's career, a marker saying This Is Where Harlan Is Now. When looking at the work I'd done after Bones, that felt intensely true of me, too. In the collected stories, there's a sign reading This Is Where Paul Is Now. Only noticeable, really, if you read the first book.

But that, also, made Everything Will Be All Right In The End easier to put together. It is about identity, parenting, the aftermath of crisis, the responsibility and burden of who you were, the weight of the decisions you make or the decisions you're avoiding. It wasn't intentional, but time after time, I found myself writing from those angles. And, using that as a guidepost, I was able to follow my rules and put the book together.

Everything starts off with "The One Thing I Wished For You," about the lengths a parent goes to in order to protect their child. It was my first post-Bones request and, honestly, I was stunned at the reception the story got when it was originally published, with people messaging me or posting about it on social media. It also punches the reader in the face thematically. How could I not start the new book with it? Without "The One Thing I Wished For You", there wouldn't be a book called Everything Will Be All Right In The End.

Like with Bones, I jumped around so that the subtexts and themes of stories flowed together. Much like with a mixtape, you can't double up in one instance (in music, it would be artists or songs from a specific record; in stories, it'd be tropes or themes or narrative tricks), and not do it for all of them.

That's why I have a story like "This Sour Ground, This Panicked Heart", an eco-horror piece involving a husband and his estranged wife, following "Every Apocalypse Is Personal", about what a parent does in the aftermath of an alien-sex invasion (yes, you read that right). Or why I follow "Well, You Asked For a Miracle", about a forgotten god hiding out in a mall during Christmas, with "I Can Give You Life," which is about a newbie state trooper discovering the strange faith the denizens follow in his territory.

I knew, again, that I wanted to make the reader have to sit back at the end of the book and kind of reassemble themselves, so that's why I chose "Detritus (Ten Pieces)," the follow up to the novella Bones Are Made To Be Broken, to end it. If the bookends of Bones were vampires and would-be parents accepting fate, then the bookends of Everything had to be parents and children, or fantasy and reality.

Comparing the two books, it's weird to say it, but Everything Will Be All Right In The End is darker than Bones Are Made To Be Broken. If you don't know me—Hi, how ya doing? Can I interest you in a book?—I wrote the stories in Bones at a time of massive personal and professional upheaval. In the introduction, I talk about walking around with helpless rage like angry hornets stuck in my skull.

But with Everything Will Be All Right In The End, I was, personally and professionally, in a better place. The hornets had calmed down, so to speak. But I was, mentally, in a worse place, filled with anxiety and confusion and a lack of really knowing what was happening, and that translated itself into the writing. Yes, the stories are more cohesive (and better? Christ, I hope so) because of it, but that cohesion led to some pretty grim avenues.

I mean, that's where the title of the book comes from. I was telling it to myself.

But that also meant it was more important than ever to get the table of contents right. I still look at Bones Are Made To Be Broken and see where I could move stuff around, change it up. The pieces were so diverse that they're adjustable, even six years later.

With Everything Will Be All Right In The End, though, I realized I had something to say, and much like those serious late-night conversations you have with your spouse or partner, you have to say them at the right time and in the right way. I knew the trick better than I had with the previous book, but that made it all the more important to me. Once I turned in the manuscript for Everything Will Be All Right In The End to my publisher, the issue would be taken out of my hands. Much like when you hit RECORD on your tape deck or BURN on your computer to put down this mix that, if you're like me, is trying to communicate how you're feeling—

It all boils down to when and how you say something.

Get Bones Are Made to Be Broken by Paul Michael Anderson at Amazon

Get Everything Will Be All Right In The End: Apocalypse Songs at Amazon

About the author

Paul Michael Anderson is the author of the collections BONES ARE MADE TO BE BROKEN and EVERYTHING WILL BE ALL RIGHT IN THE END, as well as the novellas YOU CAN'T SAVE WHAT ISN'T THERE, STANDALONE, and HOW WE BROKE (with Bracken MacLeod). He currently lives in Virginia.