Earlier this month, the National Theatre in London made its 2011 production of Frankenstein, adapted for the stage by Nick Dear and directed by Danny Boyle, available to stream for free via their YouTube page. There were two separate recordings of this play, one featuring Jonny Lee Miller as Victor Frankenstein and Benedict Cumberbatch as the Creature, and the other featuring the actors in swapped roles (Miller and Cumberbatch alternated the parts throughout the production’s run).

The motive behind this theatrical switcheroo is rooted in the themes of Mary Shelley’s classic novel and Dear’s adaptation: it highlights the dichotomy of these two supposedly different beings, the idea that they mirror each other in every way. As such, the line between man and monster, between “good” and “evil,” is so thin, it's practically invisible. However, Dear chooses to punch up this aspect of Frankenstein into truly grotesque territory, injecting his play with violence and a graphic scene showing the Creature rape Elizabeth, Victor’s betrothed. After committing this vile act, the Creature murders Elizabeth and declares, “Now I am a man.”

That there is a critique of toxic masculinity, unchecked patriarchal dominance, and society’s view of women as objects at play here is clear, but the scene is wholly unnecessary to the narrative (not to mention one of the laziest tropes in the horror handbag) and indicative of Dear’s one-dimensional interpretation of the material. The playwright views Frankenstein strictly as a father-son narrative, and while that’s technically accurate, this reading barely scratches the surface of Shelley’s multifaceted novel. Similarly, the play seems hyper-focused on heterosexual sex, and the perversion thereof, as a metaphor for the “rape of nature” that Frankenstein commits by reanimating dead tissue. This is not to say that Shelley’s novel isn’t concerned with sex and procreation and the moral ramifications of “playing God,” but, just as with the father-son dichotomy, it isn’t the only theme she explores.

Most glaringly, however, Dear’s adaptation, like so many before it, ignores the strong queer undercurrents of the narrative. The biggest exception to this literary erasure is, ironically enough, the most iconic and celebrated screen versions of Shelley’s work, Universal Pictures’s Frankenstein (1931) and its sequel Bride Of Frankenstein (1935), both directed by James Whale, one of the few openly gay men in Hollywood at that time. The latter film especially boasts a particular “gay sensibility,” as ScreenPrism’s Jay Saporito notes:

Author Christopher Bram noted the centerpiece of Bride of Frankenstein’s supposed queerness is Dr. Septimus Pretorius, archly played by the effete English actor, Ernest Thesiger, a personal friend of Whale's. ‘Whale had a lot to do with the writing of the final script,’ Bram says. ‘It's clear he saw Pretorius as an old queen in love with Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive). When Frankenstein's wife walks in, his nostrils dilate and he turns away.’

It’s true that Pretorius does interrupt the evening of Frankenstein’s wedding with the request they partner up in an attempt to create life, disabling Henry’s chance of consummating with his bride. Elizabeth (Velerie Hobson) is left by herself while the two men go off to ‘use his creativity...’

Saporito acknowledges that some might consider seeing queer undertones in Shelley’s novel as revisionist, or shoehorning modern-day values and sentiments onto classic texts. This is certainly the case with that other famous monster book, Dracula, which has gone from a distinctly xenophobic thriller to a tragic love story in the near-123 years since Bram Stoker first published the novel. But queerness in Frankenstein isn’t a stretch at all, when you begin to deconstruct the novel. Think about it’s basic premise: a mad genius becomes obsessed with creating life with his bare hands, and sets about doing so by robbing graves so as to find the choicest body parts. It isn’t enough to simply resurrect the dead, however. The being Victor Frankenstein creates must be the perfect specimen of a man. And as Rachel Chung points out in their article for Inquiries Journal, this drive for physical sublimity may be rooted in more than Frankenstein’s god complex:

Frankenstein’s uncontrollable desire incorporates a sense of peril similar to the desire for another man—both are forbidden, and both are followed by the swift and terrible retribution believed to be deserved by homosexuals in Shelley’s time...

Chung goes on to examine Shelley’s text, highlighting the language used by Frankenstein in describing his creation, exclaiming at one point that he “selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful!—Great God!” But the beauty the doctor sees in the Creature dissipates into disgust, prompting him to reject the being and abandon him. As Chung explains, this rejection stems from sexual repression:

Frankenstein describes his creation much like one might describe Michelangelo’s David—entranced by the beauty and fine detail, he almost sexualizes the monster—until he lights on the eyes. After he notices the eyes, Frankenstein’s image of the creature is suddenly macabre and grotesque...

...Frankenstein’s anxiety upon being seen by the monster imply [sic] a more chronic fear of sex. At Frankenstein’s age, it is fair to assume that he has never had a sexual relationship, especially not with Elizabeth, his betrothed. Frankenstein seems to ignore sex altogether, eschewing it in favor of study. To Frankenstein, sex and family are mutually exclusive with the success and power he seeks. He chooses to pursue power, and he creates a being entirely without the aid of the female body. Frankenstein turns sex—and Elizabeth—into something unnecessary, frivolous, and low....Frankenstein’s anxiety around sex indicates a kind of “homosexual panic” common in Gothic literature. Frankenstein can never safely acknowledge his curiosity or even the existence of the male body as a sexual object, which leads him to regard sex itself as panic-inducing.

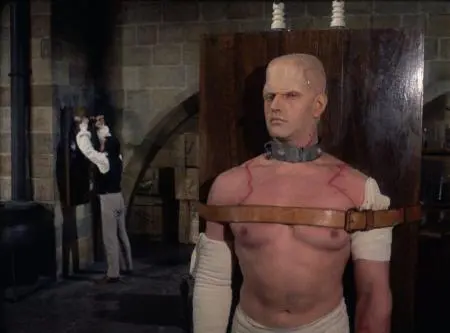

As Chung suggests, could Frankenstein indeed be a parable of repressed queerness? Plenty of filmmakers think so, from the aforementioned Whale to Jeremy Burnham and Jimmy Sangster, the men behind the Hammer sequel The Horror Of Frankenstein, which casts body builder/onscreen Darth Vader David Prowse as a mostly shirtless Creature who kills anyone threatening to expose Frankenstein’s “dark secrets,” to Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, and the bevy of other creative talents behind Flesh For Frankenstein (starring Udo Kier as the mad doctor who ignores his lusty wife whilst endlessly pursuing the creation of a hunky “Super Lover”), to Jim Sharman and Richard O’Brien, creators of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (though queerness isn’t repressed here; it’s out and proud), and numerous other creators. It’s a reading also echoed by BBC reader Emily Puleo, in response to a query from the British media giant asking fans to discuss what Shelley’s novel means to them. Puleo writes:

Influenced greatly by the Victorian paradigm of homosexuality, Lord Byron, Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein to explore the inability to ignore or destroy one's sexuality. Victor Frankenstein creates a large, masculine being in order to complement his own effeminacy and to fulfill his repressed homosexual desires. The creature acts also as a symbol of Frankenstein's sexuality. The creature pursues Frankenstein and Frankenstein pursues the creature - they have eyes for none but each other, and women act only as intermediaries between the two. Frankenstein's passion clearly overshadows his affection for Elizabeth, and a similar situation arises between the creature and his woman counterpart...Frankenstein remains unable to escape from the creature's grasp—from his homosexuality—until at last he dies. The creature dies only after Frankenstein's death, finalising Shelley's idea that homosexuality is a natural, inextinguishable trait.

Perhaps most interesting in Puleo’s comments is the suggestion that Victor Frankenstein might be based on Lord Byron, Shelley’s friend and contemporary, who did indeed inspire the young author to write her landmark novel when he challenged her and several of their friends—among them Shelley’s soon-to-be husband Percy Shelley and John Polidori, author of The Vampyre—to write the scariest story imaginable. But is there more of Lord Byron in Frankenstein than this general germination? Quite possibly. Puleo suggests Byron was homosexual, though it is more likely he was bisexual, attracted to both men and women. Not that a genuine desire for the female of the species mattered much to Victorian England, whose collective moral panic at Byron’s sexuality essentially forced the poet to flee his home country for Geneva, where that infamous stormy night at the Villa Diodati would ultimately occur. Guardian writer Fiona McCarthy notes:

The facts of Byron's exile have been glossed over by most of his biographers. Proliferating accusations of cruelty, adultery and Byron's incest with his half-sister Augusta have been taken as explanation enough—although incest was punishable by the ecclesiastical courts but not a criminal offence. It was the much more serious allegation of sodomy, a crime bearing the death sentence in homophobic early 19th-century England, that led to Byron being virtually driven out.

He was to be forever haunted by the scenes of hostility during his final weeks in England: ‘I was advised not to go to the theatres, lest I should be hissed, nor to my duty in parliament, lest I should be insulted by the way; even on the day of my departure my most intimate friend told me afterwards that he was under apprehension of violence from the people who might be assembled at the door of the carriage.’ It was feared he was in danger of lynching by the mob. In the Dover hotel some women went so far as to disguise themselves as chambermaids to get a closer look at him, as if he had become an exhibit in a freak show. The violence of this public reaction resembles the hatred that, 80 years later, was hurled at Oscar Wilde.

Byron’s experiences in England conjure images of a mob with torches and pitchforks, a staple of the Frankenstein narrative, connecting the poet to both the Creature and Victor, both “sinners” against nature. Consider also Byron’s taboo relationship with his half-sister, which is the inverse of Victor’s sterile engagement to his adopted sister Elizabeth (later editions recast her as Frankenstein’s cousin); or the fact Byron refused to acknowledge the child he fathered with Claire Clarimont as his own, which might have inspired Frankenstein’s abandonment of his child and potential mate (extending the novel’s incestuous themes); or the fact that Byron had a club foot that he took great pains to conceal, showing that he was no stranger to hiding away an aspect of himself he found “monstrous,” even if he didn’t actually give a fig what people thought of his sexual proclivities.

Perhaps the theme of repression comes from Shelley’s husband Percy. It is rumored the couple engaged in orgies with Byron, Clairmont (who was also Shelley’s stepsister), and possibly Polidori as well, and that Byron and Percy in particular shared a tremendous amount of sexual tension between them (see Ken Russell’s underrated film Gothic for onscreen depictions of such). It’s entirely possible Percy felt a sexual desire for Byron, but never acted on it, and this suppression found its way into Shelley’s work. (Other evidence that Shelley might have based her protagonist on Percy include the fact he had a sister named Elizabeth and apparently conducted science experiments as a child).

But perhaps the greatest support for the argument that Shelley consciously included queer themes in Frankenstein comes from Shelley’s own bisexuality, a fact she never discussed publicly and only revealed to a handful of her friends. Being not only queer herself but also a woman in a time when neither were respected or lionized put Shelley at a distinct advantage, if you can call it that, to understand the plight of those misunderstood and casted aside by society. She not only had to repress her own sexual desires by keeping it as private as she possibly could, Shelley was often forced to fit herself into the expected feminine box—she even admits she was only a “nearly silent listener” when Percy, Byron, and Polidori discussed “the spark of life,” a key component of Frankenstein. In this way, we see Victor and the Creature as aspects of her own character: the genius and the outcast, the great mind and the gentle soul, acknowledging that both can achieve stupefying things but also fall to darker inclinations when conditions are just right.

Again, it must be restated that Frankenstein is a novel of many meanings. It is not only a distinctly queer work, but a feminist work, a work of social critique and an examination of the human condition. To say it is only one of these things does the monumental novel a grave disservice, and to rebuild it into a hulking mess of machismo and patriarchal pontification—as Nick Dear did—is the true sin against nature.

Buy Frankenstein from Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com