The Stand is one of Stephen King's most enduring and popular works. This is due, in part, to the fact the book formally introduces one of the author's most formidable baddies, Randall Flagg, as well as the fact it's an effectively modern interpretation of the epic good versus evil narrative (King took inspiration for The Stand from The Lord Of The Rings series).

The narrative reached a wider audience via a four part miniseries that aired on ABC in 1994. It's a faithful adaptation of King's novel—scripted by King himself—and for anyone that grew up loving King and horror movies in the 1990s, it's a delicious slice of fried nostalgia pie. But is it any good? Faithful though it may be, does it do the novel justice, or is it like a bastard, sniveling half-sibling; a disappointment compared to the first-born child?

Well, that's just the sort of thing we suss out here in our Book vs. Film feature, so let's get to sussing, shall we?

The Books

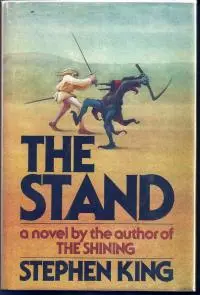

The Stand has three major editions out there: the first, published in 1978, coming in at around 900 pages, give or take; the second, in paperback, published in 1985 and more or less the same page length; and the third, the Complete & Uncut Edition from 1990, which adds about 400 pages to the text by reinstating scenes cut from the original 1978 manuscript. Let's first go through the basic differences between these editions before moving on to the miniseries.

If you're looking for a critical response to the original novel and the 1990 Complete & Uncut Edition, check out our own Meredith Borders' column here. Also, for a deeper look at the novel and miniseries' glaring problems (by 21st century standards), check out this Uproxx article from Ben Goldstein—and yes, The Stand has LOADS of problems, the biggest of all being the inclusion of both the "magical negro" and "inspirationally disadvantaged" tropes (Mother Abigail and Tom Cullen, respectively).

1978

1978

The Stand chronicles a catastrophic plague that nearly wipes out the human race. Those immune to this plague—a militarily-weaponized strain of the flu known as Captain Trips—align themselves with one of two camps: the "good" side, lead by a devout 108-year-old woman named Mother Abigail, and the "bad" side, lead by a mysterious figure known by many names, but primarily called Randall Flagg, who is not a man at all, but some kind of malevolent entity (those who share Mother Abigail's beliefs think he is either a demon or the Devil himself, though King hints that Flagg is an evil much older than any figure from The Bible).

The narrative unfolds primarily through the perspectives of four characters: Stu Redman, a plainspoken, blue-collar factory worker from East Texas; Fran Goldsmith, a twenty-something from Maine who is pregnant with a non-immune man's child (casting a big question mark over the fate of her unborn baby); Nick Andros, a deaf-mute who provides the group with cool reasoning and good cheer in equal measure; and Larry Underwood, a musician responsible for the fluffy, pre-plague disco hit "Baby Can You Dig Your Man?" (and who has more skeletons in his closet than he can handle at times). As the near-decimation of humankind gets going in earnest, these and all the other characters in the novel begin to dream of both Mother Abigail and the "dark man" Flagg, and these dreams determine which direction the characters travel—toward Nebraska, and latterly Boulder, Colorado, to "join forces" with the old woman, or toward Las Vegas, Flagg's "sinful" base of operations (think of these dreams as a sleep time Sorting Hat).

These "good characters" all become members of the "Free Zone Committee," tasked with re-establishing law and order, and serving more or less as a congress, in the repopulated Boulder. The other members of this committee are: Glen Bateman, a former sociology professor; Ralph Brentner, a big Oklahoman teddy bear; and Sue Stern, a woman who helps the Free Zone's resident engineer restore power to the city. They also have to deal with Flagg in some way, whom they know has plans to bomb Boulder off the map. In order to obtain information, they send three spies out west: Dayna Jurgens, Judge Farris (named so for his former career as a judge), and Tom Cullen, a "mildly retarded" (as King puts it) man whom the group hypnotizes in order to block his movements from the psychic eye of Flagg. Tom, it turns out, is the only spy to make it back alive.

Unfortunately, Boulder has two prominent Flagg supporters among their population. The first is Harold Lauder, a friend of Fran's from Maine and a proto-M.R.A, who desperately wants to kill Stu for "stealing" Fran away from him (in fact, Fran has no interest in him romantically). He joins forces with Nadine Cross, a woman who briefly travelled toward Mother Abigail with Larry, but eventually left him when she realized she is "promised" to Flagg as his virgin bride. Together, the pair plant a bomb in Nick's house, killing him, Sue Stern, and several other prominent members of the community during a committee meeting (Fran also suffers serious, but not fatal, injuries). Both Harold and Nadine later end up committing suicide, the latter after her traumatic, less-than-consensual sexual encounter with Flagg

This event coincides with the return of Mother Abigail from a spiritual sabbatical, who, before dying, instructs the surviving members of the committee (minus Fran) to set out on foot for Las Vegas that very evening. She tells the group she received these instructions from God.

Larry, Glen, Ralph and Stu obey. On their way, Stu tumbles down a cliffside and breaks his leg. The three men leave their friend behind at Stu's insistence—he wants them to finish what they started.

Flagg's men apprehend the trio not long after, and imprison them in Las Vegas. Lloyd Henreid, Flagg's right-hand man, shoots Glen in his prison cell, while the other henchman lead Larry and Ralph to a platform outside the MGM Grand Casino. Flagg plans to publicly draw and quarter the men, but just before he can carry out the execution, a wary member of Flagg's security breaks rank and pleads with the crowd to turn against their leader. Flagg zaps him with a ball of energy that kills the man, then rises up into the sky. Again, before the execution can continue, the Trash Can Man—a deranged pyromaniac devoted only to fire and Flagg—shows up with an atomic bomb as an offering to his master. The ball of energy, morphing and distending into something that vaguely resembles a giant hand (Ralph believes it is the Hand of God), descends from the sky, wraps itself around the bomb and sets it off. Larry, Ralph, and everyone in Las Vegas perishes, though Flagg transforms into a strange, hunkering creature before disappearing, escaping the blast.

In the novel's falling action, Tom reconnects with Stu, and the pair travel back to Boulder. There is concern about Fran's baby, Peter, who contracted Captain Trips shortly after birth. But because Peter had one parent who was immune, he manages to fight off the sickness.

Fran becomes homesick and wishes to see Maine again, so she and Stu set off with baby Peter in tow. But they're not sure if they'll ever return to Boulder again—the citizens there recently elected a sheriff whose first priority is to arm and beef up the police force. It seems the legacy of human brutality will repeat itself again. The last scene in the book has Fran asking Stu if people will ever learn from their mistakes.

His response: "I don't know."

His response: "I don't know."

This is a fitting close to a novel that grapples not only with good and evil, but the almost unwitting complicity with which good people engage in evil. Our fear drives us to blindly follow powerful, charismatic people, trusting that they will make the correct decisions and keep us safe. It was this same fear that led to the development of Captain Trips in the first place, fear motivated Randall Flagg's ascension in Las Vegas, and fear also motivated the citizens of the Free Zone to both blindly trust the original committee led by Stu and the others, and the new sheriff who seems to put most of his faith in the adage "shoot first, ask questions later." Were the people in Boulder really all that different from those in Las Vegas? King portrays those outside of Flagg's immediate circle as people more or less trying to do their best in an impossible situation, after all. And was Mother Abigail that much different from Flagg? The simple answer is yes, of course, but Abigail herself struggled with the demigod status the Free Zone citizens forced upon her (and her secret love of the adulation). She certainly had goodness in her heart, as did Stu, Nick, Larry, Fran, and the rest. But did everyone else?

Just as Stu states, we just don't know.

1985

For the paperback edition of The Stand, published in 1985, King made some minor updates and improvements to the original text. There isn't much discernibly different from the 1978 edition, save for the update in timeline—instead of the action taking place from 1980-1981, it occurs from 1985-1986. Also, King removed any mention of "Baby Can You Dig Your Man" being a disco hit, as that reference was, by the mid-'80s, already terribly outdated. He never specifies what genre the song falls into, but rest assured, it isn't disco.

1990

1990

By 1990, King was a megastar, and for this reason (i.e., because it would in all likelihood sell like hotcakes) Doubleday published the Complete & Uncut Edition of The Stand, re-inserting all the scenes cut from the original 1978 publication. The timeline gets another update, as do other references (Larry's song, for instance, is not only de-discoed, but it becomes a kind of bluesy, soulful rock song, like a pithier version of something Bruce Springsteen might record).

There are also two brand new scenes, an epilogue and prologue: the former, titled "The Circle Opens," goes into greater detail about the development and release of Captain Trips upon the world; the latter, "The Circle Closes," shows Randall Flagg waking up on a beach and reinstating himself as a god among the indigenous people of the South Pacific. The titles of these additions further speak to the circuitous nature of humanity outlined in the first edition's final pages, our propensity to doom ourselves over and over again, but with less of a question mark hanging over the matter. Instead of Stu's "I don't know," it seems this new ending is a definitive yes—history will indeed repeat itself; what has happened will happen again.

But perhaps the most memorable change (and not in a good way) concerns Trash Can Man and his journey with a character known as The Kid. In the original text, we see only a brief flashback to Trash's time with the Kid, as well as a glimpse late in the novel into the Kid's fate (a wolf rips his throat out). In the Complete & Uncut Edition, however, King scripts out the entire subplot, including a scene in which the Kid sodomizes Trash Can Man with the barrel of a gun. The prolonged sequence does little to enhance the overall narrative, and the "gun buggery," as the aforementioned Meredith Borders calls it, shocks and appalls without really enhancing our understanding of either character.

There are some additions to this expanded text that do work—Borders in particular loved the extended flashback between Fran and her mother, feeling the scene made Fran a more rounded character—but overall, it's really only important to King completists who must read everything the man ever published. Even those who love King (and I include myself in this camp) are better off sticking to either the 1978 or 1985 texts, which are fairly easy to come by in used book stores and online.

The Miniseries

When executives and King finally reached a deal to turn The Stand into a TV miniseries, it's entirely possible that the neutral to negative reviews of the Complete & Uncut Edition influenced King to adapt his original novel, rather than the expanded edition. Possibly not, but since time constraints were a factor anyway—the entire narrative had to be told over eight hours, in four two-hour installments—it made sense to re-jettison all the new content included in the 1990 republication (not to mention, the American Broadcast Company wouldn't allow "gun buggery" in one of their programs, even though a brief scene of Randall Flagg raping Nadine did make the cut).

King overall did a fine job of compartmentalizing the narrative for the screen, even further scaling back certain sequences and omitting entire characters to better streamline the narrative. For instance, in the novel, Larry travels out of New York City (via the Lincoln Tunnel, one of the book's most horrifying scenes) with a woman named Rita Blakemoor, whom he met a few days prior in Central Park. Rita has a pill problem, and later dies of an accidental overdose, leaving Larry vulnerable and afraid of companionship. That changes when he meets up with Nadine Cross, who travels with a near-feral boy she calls Joe. The three begin traveling together toward Boulder, where they pick up several others along the way, namely Lucy Swann, who becomes Larry's lover after Nadine disappears. In the miniseries, however, Rita does not appear, as King combines her with Nadine. Joe also travels with Lucy, leaving Nadine emotionally isolated throughout most the narrative. This is actually an improvement over the original narrative: not only does it work to beef up Nadine's character, Rita's presence in the novel only prolongs Larry's storyline, and he's a far less interesting character than Stu, Nick, Fran, and the others.

However, even though King substantially thinned-out his sprawling epic for the screen, the miniseries as a whole loses a lot of its steam about midway through. The first part, subtitled "The Plague," which introduces us to the main players all while detailing the collapse of civilization, is a fine example of television filmmaking, but the other three installments fail to deliver the same emotional punch. The only other highlight is the solidly taut house bombing sequence, the climax of which truly devastates the audience, since it ends with the death of Nick Andros, played tremendously well by Rob Lowe, easily one of the most enjoyable characters of the series.

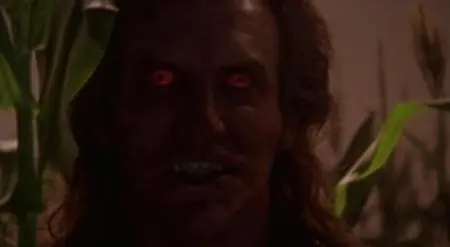

Speaking of the cast, Gary Sinise couldn't be a better fit for Stu Redman, as the actor masters the Texas drawl and embodies the character's straight-shooting simplicity (which is not to say Stu is unintelligent, he just doesn't overthink things). Jamey Sheridan as Randall Flagg also stands out, handling the character's gleeful monstrosity quite well. Laura San Giacomo as Nadine, Ruby Dee as Mother Abigail, Miguel Ferrer as Lloyd Henreid, and Ossie Davis as The Judge all deserve praise as well.

The good performances don't make up for the slow pacing that bedevils the bulk of the series, however. Moreover, King and director Mick Garris eschew the novel's religious ambiguity and more or less state full-on that, yes, Randall Flagg is the Devil, and yes, that IS the hand of God swooping in at the end to set off the nuke (and not simply an amorphous ball of energy that kind of sort of looks like a big hand to Ralph, a man already predisposed to believe in something like the Hand of God). And while the miniseries certainly isn't the worst thing a person could spend their time watching (looking at you, The Langoliers), for the richest experience of The Stand, the book definitely outshines its adaptation.

Get The Stand at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Stand Miniseries at Amazon

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com