It: Chapter Two hit theaters on September 6th, 2019, debuting at number one at the box office, demonstrating once again the timeless appeal of a deranged clown/multidimensional being stalking and murdering children. Based on the 1986 novel It by Stephen King, Chapter Two—as you might expect from the title—is the continuation of It: Chapter One, released in 2017. And as with the first installment of this sprawling, generation-spanning narrative, Chapter Two featured several nods to the 1990 miniseries, originally airing on ABC and starring Tim Curry as the titular monster also known as Pennywise the Dancing Clown (Bill Skarsgård plays the role in the new adaptation).

So what is it about this story that continues to fascinate readers and moviegoers over thirty years after the book's publication? And how do the two separate screen versions of It compare to King's original text?

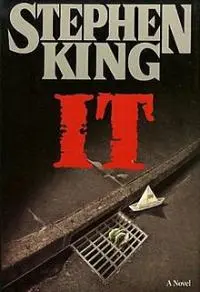

Well, we're not going to talk about that. Not directly, anyway. We're going to do something a little different this time around. See, as indicated above (note the word "sprawling"), It is a long, long, long, long book. And dense. In its original hardcover edition, it clocked in at 1,138 pages, and it follows, with King's knack for detail, seven main characters, a handful of side characters, and the rich, bloody history of Derry, Maine, the story's fictional backdrop (though heavily based on the author's home, Bangor). It would be quite the endeavor to satisfactorily go through the novel and its themes and compare/contrast them with the TV and feature film versions, all of which combined sport about an eight hour runtime.

Instead, let's look at one character from the narrative, Beverly, examining her depiction and function in the novel—including her place in the larger thematic context—and how the miniseries and films both honor, revitalize, and even subvert King's original intent.

And yes, this means we're going to be talking about THAT scene, maybe the most infamous in the book, and a scene that has never, and likely will never—if there are future adaptations—make it to the screen. If you're familiar with It in any capacity, you know the one I mean. And if you don't, read on to find out...

The Novel

First off, it's important to mention the novel's structure here, which is divided into two primary narratives taking place in 1957-1958 and 1984-1985, respectively. The first timespan tells the story of the Loser's Club, seven preteen kids who are outcasts in some capacity, all of whom are picked on by various bullies, with their primary human antagonists being Henry Bowers and his gang of lackeys. More than this, however, they are terrorized by an evil entity they refer to as It, which often takes the form of a clown named Pennywise. They realize all Derry adults are blind to this nightmare figure, so they resolve to fight the monster themselves.

First off, it's important to mention the novel's structure here, which is divided into two primary narratives taking place in 1957-1958 and 1984-1985, respectively. The first timespan tells the story of the Loser's Club, seven preteen kids who are outcasts in some capacity, all of whom are picked on by various bullies, with their primary human antagonists being Henry Bowers and his gang of lackeys. More than this, however, they are terrorized by an evil entity they refer to as It, which often takes the form of a clown named Pennywise. They realize all Derry adults are blind to this nightmare figure, so they resolve to fight the monster themselves.

The second timespan follows the Losers as adults, who are drawn back to Derry 27 years later to once again battle It, realizing they were unsuccessful in killing the entity in their childhood. King alternates between these two periods, beginning with Pennywise slaying Bill Denbrough's brother Georgie in 1957, then the clown's killing of Adrian Mellon in 1984 following a hideous hate crime against the man, and so on, back and forth, until we reach the dual climaxes of each narrative.

The novel is primarily about memory, specifically how memories of childhood become like half-forgotten dreams the older we get, especially the more traumatic aspects, the nightmares. King's point here is that the nightmares never really leave us, and at some point we must confront them before we can completely move on with our lives. Beverly's character arc explores this theme through the transition of girlhood to womanhood as a kind of patriarchal-inflicted nightmare, both figuratively with the general threat of boys and men lusting after her "ripening" female body, and literally, given that Bev's abusive, unstable father Al is quickly turning into one of those lusting men. It is no wonder, then, that Pennywise's most memorable attack on Beverly involves a fount of blood spewing out of her bathroom sink, spraying both the girl and the walls around her—a metaphor for looming menstruation, a biological occurrence that many people equate to "becoming a woman."

In our first glimpse of the character as an adult, we see that Beverly, now a genius businessperson, runs a wildly successful fashion enterprise with her husband, Tom. We also learn that Tom doesn't really do anything in the company except take credit for Beverly's work, and that—more importantly, more damningly—he abuses her with more ferocity than her father, physically, verbally, and emotionally. This is sadly typical of many women who suffered abuse in their childhood, only to enter into abusive relationships later in their life; moreover, this is an integral part of Beverly's narrative arc, which, like everything in It, is cyclic, most prominently represented by the titular creature's deadly reemergence roughly every three decades. When Mike calls her back to Derry to once again battle It, Tom accuses Beverly of cheating on him and beats her with a belt, an act with rather unnerving fatherly undertones. But while these "whuppins," as Tom calls them, usually work to quell any perceived rebelliousness in Beverly, in this instance, something happens: Beverly actually fights back. Tom is utterly befuddled at this; in all previous beatings, the status quo—his dominance, her subservience—had been restored. But after she bests him physically, Beverly verbally lays down the law:

"Tom, listen to me." She spoke slowly. Her gaze was very clear. "If you come near me again, I'll kill you. Do you understand that, you tub of guts? I'll kill you."

This sudden empowerment, this determination to fight, has everything to do with the phone call from Mike, the reminder of her childhood battle with evil. Beverly doesn't fully realize it yet, but she subconsciously understands just how powerful she is, that she has stood up to more frightening figures than her tubby husband. As the novel progresses, and as Beverly confronts her past, she recalls more of the horrendous abuse she suffered at the hands of her father, but she also remembers that she was the best out of her fellow Losers at handling a slingshot—not only the best, she blows them all out of the water, hitting targets with almost preternatural skill, a born marks-person (much like her stunning affinity for business affairs in adulthood). King alludes to the idea that each child has a particular role to play in the fight against evil, that they've been brought together by some cosmic force to stand against It (and they have, to a degree, by a giant space turtle).

But this badassery with a slingshot is ultimately not Beverly's primary function in the battle against It. She has a greater power that emerges after they've (temporarily) defeated the monster down in the sewers.

So yeah...it's time to talk about THAT scene.

Some call it an orgy, but that's really not the best word for what happens. Orgy is really too salacious. But yes, Beverly does have sex with all six boys in succession down in the sewer.

Let's turn to Grady Hendrix and his thorough examination of the novel for some context, shall we?

...the kids...are stumbling around lost in the sewers, unable to find the exit. As a magical ritual, Beverly has sex with each of the boys in turn. She has an orgasm, and afterwards they are able to ground themselves and find their way out of the sewers. Readers have done everything from call King a pedophile to claim it’s sexist, a lapse of good taste, or an unforgiveable [sic] breech of trust. But, in a sense, it’s the heart of the book.

It draws a hard border between childhood and adulthood and the people on either side of that fence may as well be two separate species. The passage of that border is usually sex, and losing your virginity is the stamp in your passport that lets you know that you are no longer a child (sexual maturity, in most cultures, occurs around 12 or 13 years old). Beverly is the one in the book who helps her friends go from being magical, simple children to complicated, real adults. If there’s any doubt that this is the heart of the book then check out the title. After all “It” is what we call sex before we have it. 'Did you do it? Did he want to do it? Are they doing it?'

Hendrix goes on to explain that each member of the Losers Club must face their fears and shortcomings to gain power, stating, "Beverly has to have sex (and good sex—the kind that heals, reaffirms, draws people closer together, and produces orgasms) because her weakness is that she’s a woman." This isn't meant to be a reductive statement: each child is an archetype of bullied and marginalized people: Bill has a speech impediment, Eddie is a "sissy" and a germophobe, Ben is fat, Richie is an overactive loudmouth, Stan is a geek and Jewish, Mike is black, and Beverly is a girl. And as Hendrix points out, since all the Losers make strengths of their weaknesses, it makes sense that Beverly would embrace her sexuality and feminine power, given that her looming womanhood is her biggest source of terror. Furthermore, remembering this sexual act in the sewer, this display of her power, allows Beverly to finally break her cycle and enter into a relationship with Ben, who is loving and caring and would never hurt her, physically or otherwise.

Still, there are numerous problems with this character arc, especially for modern readers. Primarily, it offers a somewhat traditional and decidedly heteronormative view of femininity and womanhood, given that Beverly's sexual awakening and cycle-breaking relies on the presence of men. Consider too that after It kills Eddie in the adult sequences, Beverly elects to stay behind with his corpse while the other men end the fight once and for all, insisting they shouldn't leave him alone—casting her as the mother and the caregiver in this instance, even though there is nothing she can do for Eddie at this point. Altogether, this definitely isn't the worst thing a straight white man has ever written about a woman—not by a long shot—but it does feel a bit outdated today.

The Miniseries

First off, no sex in the sewer here! There will never be a screen version of It that keeps this scene intact. It works on the page (just barely), but it simply won't work elsewhere.

This isn't the only scene cut or truncated from the novel, of course. As a miniseries developed for network television, there wasn't a lot that screenwriter Lawrence D. Cohen, director Tommy Lee Wallace, and the other filmmakers could actually show. While there is a fair amount of blood over the course of parts one and two (collectively about three hours), it gushes out of photo albums, spews from sink drains, spatters out of popped balloons, and oozes from fortune cookies, but hardly ever does it come from people.

But while Beverly's iconic bathroom bloodbath remains intact, the abuse she endures at the hands of her father is scaled back quite a bit, with the threat of sexual abuse all but nonexistent. Despite these cuts, however, Beverly's essential character arc still comes across. Much like in the book, we first see her fall victim to her husband, only to fight back for the first time in their relationship (complete with the threat of murder should he hit her again). By confronting the abuse suffered at the hands of her father and reconnecting with her childhood powers, she is able to break the cycle and be with a man (Ben) who respects her, even idolizes her. And without the sewer sex, Beverly's true power lies in her preternatural ability with the slingshot, and it is for this reason alone that the giant space turtle guides her into friendship with the Losers (or so we can assume; the turtle doesn't actually appear in the miniseries).

The filmmakers symbolize this forgetting then regaining of her strength by depicting young Beverly (played by Emily Perkins) mostly in jeans and boyish blouses; as an adult (portrayed by Annette O'Toole), she wears mainly dresses and skirts, but changes into jeans for their descent into the sewer. She also gets to participate in the final killing of It, helping her friends rip the heart out of the creature in the form of a giant spider. This not only removes some of the motherly undertones present in the novel (staying with Eddie's corpse) but it makes more sense from a story standpoint, given how the group is at their most powerful when they work together. Overall, the miniseries suffers from not-so-great (but not terrible) performances from the adult actors, a small budget (that spider at the end isn't too impressive), and the restraints of television standards and practices that kept the films from really "going there," but its depiction of Beverly is by and large and improvement from King's novel.

The Films

You guessed it! No sewer sex!

There is much to like about this new version of Beverly, particularly in It: Chapter One (played in this first installment by Sophia Lillis). She's much closer to her literary counterpart here—a cigarette-smoking, take-no-shit kind of girl. She does, however, take all kinds of shit, which is part of her tough persona, a mask she wears to hide her pain. She takes the most shit from her dad, with his physical violence now on full display (you can get away with a lot more in an R-rated feature film). Screenwriters Chase Palmer, Cary Joji Fukunaga, and Gary Dauberman, as well as director Andy Muschietti, also introduce the element of sexual abuse mostly absent from the miniseries, as well as add a new element: slut-shaming and bullying from her peers, primarily Greta (Megan Carpentier), a character from the novel that only briefly appears in the miniseries.

The scene involves Greta dumping a bag of wet garbage on Beverly as she sits in a graffiti-smattered bathroom stall attempting to sneak a smoke. In Chapter Two, It transports Beverly (now played by Jessica Chastain) back to this "slut-shaming cage," where the monster also shape-shifts into a litany of real-life demons from her childhood, including Greta, Henry Bowers (Nicholas Hamilton), Mr. Keene (Joe Bostick), the lascivious middle-aged pharmacist who flirts with Bev in the first film, and of course her own father (Stephen Bogaert). Beverly's promiscuity is only a rumor, but regardless, the two scenes highlight how other girls and women participate in the patriarchal system of demonizing sexuality, which further informs Beverly's tolerance of abuse from her father and the other boys/men in her life.

But as progressive as this is new element to the plot is, much of Beverly's overall character arc in the films feels a bit regressive. While the filmmakers heavily allude to the giant space turtle throughout chapters one and two, it isn't shown, and there are no further references to a cosmic force guiding the Loser's Club. As such, Beverly is no longer the slingshot queen, becoming instead a damsel in distress that must be saved by the boys in Chapter One. There's even a "kiss from a prince" (Ben, played by Jeremy Ray Taylor) to revive her from a deadlights-induced coma. It isn't until Chapter Two that we get some payoff for this scene. She tells Ben (Jay Ryan in the second installment) the poem he wrote for her ("Your hair is winter fire / January embers / My heart burns there too") made her feel special, like more than just a piece of meat, as all other boys and men treat her, so his literal saving her in the first installment was symbolic of saving her emotionally. In a world of bullies that shame her for being a girl on her way to womanhood, he made her feel beautiful and powerful. She is able to tap into this power and, in turn, save Ben's life in Chapter Two. As she is trapped in the nightmare bathroom stall, she kicks down the door and rescues Ben, who is literally drowning under his own shoddy construction work (which would be more poignant for Ben if he'd been a natural architect in his youth, but the filmmakers scrapped this aspect of the character). This leads to their romantic union, and the breaking of Bev's abusive cycle, which is of course the same completion of Beverly's arc seen in both the original novel and the miniseries.

However, while the destination of the arc is the same, it overall isn't as pointed as in King's text and the previous screen adaptation. This is mostly because Muschietti and company omit the line, "If you come near me again, I'll kill you." As such, it isn't entirely clear that this is the first time Beverly has actually fought back, that in hearing again from Mike and remembering some of the power she had in childhood, she is able to rise up and escape her abusive, piece of shit husband. Without this line and the more prominent story arc, watching Tom mercilessly beat Beverly feels almost gratuitous, just another dangerous situation from which the character must escape, and not a moment integral to her character development. But at least she does get to crush It's still-beating heart alongside the men at the end of the movie. No waiting around with Eddie's corpse for Beverly here!

Overall, whether we're talking about King's novel, the miniseries, or the pair of theatrical films, Beverly is a fascinating and flawed character, both in good ways and bad—good, in that she is emblematic of society's horrendous domestic violence problem and the toll it takes on its victims; bad, because in all her incarnations, she feels like a missed opportunity, like the men behind her conception could have done a little bit more, taken her just a bit further and done something truly special with her. Perhaps there will be another adaptation of It down the line, one that will finally trade in sewer sex for a power more badass than even stellar slingshot abilities.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com