As Malcolm Jones correctly opines in an article for The Daily Beast, "Ask anyone today who wrote The Birds, and the odds are good that you’ll get a blank stare for a response." This is certainly true of cinephiles, as well as the population at large, who think, no doubt, of three things when reminded of The Birds: Hitchcock, Tipi Hedren in her green dress getting jabbed and pummeled by the titular avians, and a farmer with his eyes pecked out.

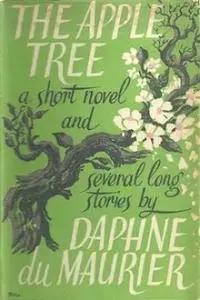

But us literary folk, while we certainly recall these images too, are quick to remind everyone that the original premise of Hitchcock's film came from a short story of the same name, written by another English master of suspense and the macabre, Daphne du Maurier. First published in 1952 within her collection The Apple Tree, "The Birds" has since been the basis for radio dramas, stage adaptations and, the subject of our discussion today, three separate screen versions, one for television 11 years prior to Hitchcock's film, and a TV movie pseudo-sequel to Hitch's picture, appearing on Showtime 31 years after The Birds.

As always, the central question is this: which of these filmed adaptations best captures the spirit of du Maurier's original text. Let's find out.

The Short Story (1952)

When considering the influences on George Romero's Night of the Living Dead, critics often point to Alfred Hitchcock's adaptation of "The Birds", but in reality, du Maurier's original work has much more in common with Romero's film. One, because her story is far more claustrophobic than Hitchcock's cinematic vision—the family's small cottage, boarded up and barricaded against winged enemies, brings to mind the seemingly ever-tightening, hastily zombie-proofed walls of Romero's rural Pennsylvania farmhouse—and two, because it features strong underlying socio-political commentary. But whereas Romero had his sights set on Vietnam-era America, du Maurier used her story to examine, from a post-war vantage point, the rather lackadaisical attitudes of both Britain and the United States toward the rise of fascism in Europe.

When considering the influences on George Romero's Night of the Living Dead, critics often point to Alfred Hitchcock's adaptation of "The Birds", but in reality, du Maurier's original work has much more in common with Romero's film. One, because her story is far more claustrophobic than Hitchcock's cinematic vision—the family's small cottage, boarded up and barricaded against winged enemies, brings to mind the seemingly ever-tightening, hastily zombie-proofed walls of Romero's rural Pennsylvania farmhouse—and two, because it features strong underlying socio-political commentary. But whereas Romero had his sights set on Vietnam-era America, du Maurier used her story to examine, from a post-war vantage point, the rather lackadaisical attitudes of both Britain and the United States toward the rise of fascism in Europe.

Du Maurier's story takes place in Cornwall, a rural English coastal town, and centers on the efforts of Nat, a war veteran and part-time farmhand, to protect his family against hordes of fowl that have been attacking human beings on sight. Theories abound as to why the titular animals have turned on humanity—a freak early onset of winter, hunger, the turning of the tides—but the author provides no concrete explanation, leaving, ultimately, the chaos of the universe as our only answer. Symbolically speaking, however, the birds seem to represent the forces of Germany, Italy, and the Axis Powers of World War II, not merely for their merciless brutality, but also for the ignorance all the citizens of Cornwall and London (minus Nat and his family) show toward the threat. They laugh off the ordeal as nonsense, and seem to think it will all blow over, or at least be handled by other powers, absolving them from taking any responsibility, of protecting themselves and others. These sentiments echo those of numerous citizens and government officials alike; prior to all-out war breaking out, it simply wasn't their problem, and they needn't worry themselves about it.

And this attitude would be fine and well if it didn't effect the entire populace, not merely those who shrug their shoulders and dismiss the problem outright. But du Maurier illustrates, with sobering horror, the damage these laissez-fare attitudes have on Nat and his family, especially with her bleak ending, which seems to suggest that, despite their best efforts to survive this strange shift in the inter-special pecking order, death will eventually come for them as well.

Danger: The Birds (1955)

Information on this CBS TV series is scant at best, to say nothing of its final episode, broadcast on May 31, 1955, which was the very first screen adaptation of du Maurier's story. Danger was a live show presenting tales of suspense and mystery, so one wonders how they pulled off scores of birds attacking a family over the course of two nights in real time. It is possible (though tricky to confirm, given the lack of details) that the producers and screenwriter James P. Cavanagh, who also adapted du Maurier's "Kiss Me Again, Stranger" for another CBS show, Suspense, two years prior, took a minimalist approach to the material. Perhaps viewers only hears the animals pecking and scraping at the cottage—a device that was, according to David Thomson in his foreword to the collection The Birds and Other Stories, suggested to Hitchcock by author and screenwriter James Kennaway, though of course, the director passed on the idea.

This approach isn't an altogether bad one, however, since much of the story's psychological dread comes from the awful sounds of the birds tearing away at the family's home, while "suicide bombers" fling themselves at the barricades, their bodies thudding horribly against the boarded windows and walls. Playwright Conor McPherson's 2009 stage play of The Birds relies on sound rather than vision as well, with maybe a smattering of feathers and blood, but no birds, real or fake, in sight. But again, whether or not this was the direction Danger took, this writer cannot say. (If anyone has access to information about the show and this episode, I'd love to hear it!)

The Birds (1963)

In that aforementioned foreword, David Thomson relates an exchange between Francois Truffaut and Alfred Hitchcock, in which the french director asked the Englishman how many times he read du Maurier's short story while preparing the script for The Birds. Hitchcock's response?

What I do is to read a story only once, and if I like the basic idea, I just forget all about the book and start to create cinema. Today I would be unable to tell you the story of Daphne du Maurier's 'The Birds.' I read it only once, and very quickly at that. An author takes three or four years to write a fine novel; it's his whole life. Then other people take over completely.

Indeed, Hitchcock forgot much of du Maurier's tale and created his own story out of her basic premise—and, in the above passage, he also seems to forget "The Birds" is a short story, not a novel (at best it's a novelette), and that du Maurier is a woman; but then again, Hitchcock didn't much care about women to begin with, as is evidenced by his horrible treatment of Tippi Hedren on the set The Birds (and later Marnie as well), especially the scene in which her character, Melanie, suffers a brutal bird attack toward the end of the film.

Much has been made of the sexual dynamics of Melanie and Rod Taylor's Mitch, especially in relation to Mitch's mother Lydia, played by Jessica Tandy. She's the domineering type who doesn't approve of her son's romantic interest in Melanie. Is it Lydia's reverse-Electra complex that instigates, as J.G. Ballard quoting Camille Paglia insists, "an explosion of 'primitive forces of sex and appetite that have been subdued but never fully tamed'"? Or, as Ballard alone surmises:

...the [bird] attacks are an external display of the mother's repressed sexual frenzy, an hysterical outburst that jumps space-time and the species barrier in a way that all great mythologies would have understood.

Maybe. Or Maybe Thomson's still on the money:

...who cared why the birds attacked or what it meant or symbolized? Hitch just wanted to do every trick with real birds that the cinema was then capable of. He liked the idea because of the huge technical challenge it represented. He had—if you like—become a very artistic film director, not overly interested in why things happened.

Whether you agree with the psychological readings of Hitchcock's film, or think the movie's nothing more than a thriller predicated on chaos, one cannot argue that du Maurier's original text feels far more relevant to our current political climate than Hitch's work. This isn't to say The Birds is a bad film (it isn't), nor that it cannot be enjoyed today (it can, provided you overlook certain unsettling aspects of its production and the repulsive behavior of its director), but when it comes to timeless narratives that resonate no matter the generation reading it, du Maurier's story wins, hands down.

![]() The Birds II: Land's End (1994)

The Birds II: Land's End (1994)

Marketed as a sequel to Hitch's film, but in fact not connected to The Birds at all (save one old man who references a similar bird attack thirty years before and the return of Tippi Hedren, though she plays a completely different character in this film). The Birds II: Land's End is a slightly more faithful adaptation of du Maurier's original story, this time with a more ecological bent; as Hedren states, "This time, we are trying to show that man screwed up the planet so desperately the birds are retaliating."

Make no mistake, however: this isn't a good film. It was directed by Rick Rosenthal, who helmed the better-than-it-should-be Halloween II (1981) and the atrocious Halloween: Resurrection. He left his name on the latter, but chose the nom-de-plume Alan Smithee for Land's End—the credit filmmakers used when they didn't want their actual name associated with a particularly bad film.

Just to reiterate: Rosenthal didn't mind taking credit for Halloween: Resurrection, but did not wish people to know he directed The Birds II: Land's End.

In case it isn't clear, this isn't a movie you should seek out, and everyone involved with it seems to agree, since it's been out of print for the last 25 years or so. But if you're at all curious about it, this behind the scenes featurette from the VHS tape will suffice:

Any fans of du Maurier's original story? What's your take on Hitchcock's film, as well as the two other little-seen screen adaptations? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section below, or on our social media posts for this article.

Get The Birds and Other Stories at Amazon

Get The Birds (film) at Amazon

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com

The Birds II: Land's End (1994)

The Birds II: Land's End (1994)