In 2017, Hulu's series The Handmaid's Tale debuted, offering viewers a chilling glimpse into a not-so-distant dystopian future that seems quite plausible, given the (still) current real-world political climate of regression, oppression, and fascistic/theocratic leadership tendencies. Creator Bruce Miller and the series's writers created a world distinctly inspired by Trump's America, but of course its source material, Margaret Atwood's seminal 1985 novel of the same name, was born from another conservative presidency that regularly blurred the lines between church and state: that of Ronald Reagan, a former actor turned politician. There are certainly parallels between the two men, and Reagan was no friend to women's rights, as Atwood was always quick to point out while publicizing the book upon its release.

This is the phenomenon of history repeating itself, and as such, a narrative like The Handmaid's Tale entering (or re-entering) the public consciousness is essential because it holds a crystal ball up to society and says, "This is where we're headed."

However, both Atwood's novel and the TV series go much deeper than that, showing us that while a draconian and dictatorial regime that forces women into non-consensual breeding programs is the "logical end," as Atwood calls it, to the wedding of evangelicalism and government, when you take the extreme nadir out of the equation, the author and series creators aren't just holding up a crystal ball, but the proverbial mirror to society; they're not only saying, "This is where we're headed," but also in many ways, "We are already here." The core difference between novel and series is how the protagonist—only ever called Offred in the novel, but revealed to be June in the series—reacts to this restrictive and terrifying society. Each are unique in their own ways, and integral to the overarching themes both shared and individual to the respective mediums.

Lost somewhere in the middle of all this is the 1990 cinematic adaptation of The Handmaid's Tale, written by venerable playwright Harold Pinter and directed by Volker Schlöndorff, perhaps most famous for another literary adaptation, The Tin Drum (1979). To say this movie has been lost to history would not be incorrect: it rarely if ever shows up on the various streaming services out there, and though it's still in print via MGM and Shout Select, you're likely hard-pressed to find anyone that even knows it exits, let alone has seen it. It isn't a bad film, per se, though it isn't really a good one either, and its poorer qualities might not be entirely the fault of the cast and crew (more on that in a bit). In some ways it's a more faithful adaptation than the series, but in other ways—those that really count—it doesn't come close to the novel at all.

Let's begin with the key elements of the book and examine each screen adaptation in kind.

The Book

For anyone unaware, The Handmaid's Tale is told, in first person, by a woman forced to become a Handmaid, the aforementioned breeding program instituted by the Republic of Gilead, a theocracy founded by right-wing militants following their deposing of the United States. We learn that the birthing rates in America were at a record low mostly due to chemical spills, nuclear incidents, and other environmental disasters, though Gilead's most staunch believers blame homosexuality, women's liberation, birth control, and abortion as the "true" culprits. We only ever know this woman as Offred, a portmanteau derived from the words "of" and "Fred," or belonging to Fred, the first name of her Commander. Every Handmaid, or women proven to be fertile, receives a new name in this way, depending on which Commander they serve, thus the important side characters Ofglen and Ofwarren (the latter is also known as Janine, her true name in the "before time"). Each month, the Handmaids must take part in a sex ritual whereby they lay their heads in the lap of the Wife of the household while the Commander effectively rapes the Handmaid, an act justified with the story of Rachel and Leah in The Bible. Each evening of the Ceremony, the Commander reads this Bible passage to the entire household—including the Marthas (combined housekeepers and cooks) and anyone else who lives in their home—before retiring to the bedroom with his Wife and government-issued fertility concubine.

The novel is overall introspective, as Offred describes what daily life as a Handmaid looks like, while at the same time sharing her remembrances of "the time before," particularly her relationship with Moira, a close friend that happened to land in the same "Red Center" (or Handmaid training facility, overseen by the Aunts and their sanctimonious, sadistic leader Aunt Lydia), a woman Offred admires because she held on to her take-no-shit attitude and managed to escape the Center. Offred is also haunted by the memory of losing her husband Luke and daughter Hannah, both of whom may or may not be dead (they attempted to escape, but were ambushed near the Canadian border by Gilead soldiers). When not reflecting on her past, Offred contends with the Commander, who wants to make her his full-time mistress (outside of breeding nights and with his Wife, Serena Joy, not in the room). Serena, meanwhile, plans to breed Offred and the Commander's driver Nick, since it is clear the Commander is sterile and Serena just wants Offred out of there as quickly as possible. This plot in turn causes Offred to develop feelings for Nick, both sexual and emotional; she also begins to suspect he is either a rebel or an Eye, a member of a secret organization that keeps tabs on everyone in Gilead, Handmaids and Commanders alike. Finally, Offred learns of an active resistance movement through one of her fellow Handmaids, Ofglen. Because her Commander is so high up the food chain, Ofglen asks Offred to spy on him and relay any information she can.

The novel is overall introspective, as Offred describes what daily life as a Handmaid looks like, while at the same time sharing her remembrances of "the time before," particularly her relationship with Moira, a close friend that happened to land in the same "Red Center" (or Handmaid training facility, overseen by the Aunts and their sanctimonious, sadistic leader Aunt Lydia), a woman Offred admires because she held on to her take-no-shit attitude and managed to escape the Center. Offred is also haunted by the memory of losing her husband Luke and daughter Hannah, both of whom may or may not be dead (they attempted to escape, but were ambushed near the Canadian border by Gilead soldiers). When not reflecting on her past, Offred contends with the Commander, who wants to make her his full-time mistress (outside of breeding nights and with his Wife, Serena Joy, not in the room). Serena, meanwhile, plans to breed Offred and the Commander's driver Nick, since it is clear the Commander is sterile and Serena just wants Offred out of there as quickly as possible. This plot in turn causes Offred to develop feelings for Nick, both sexual and emotional; she also begins to suspect he is either a rebel or an Eye, a member of a secret organization that keeps tabs on everyone in Gilead, Handmaids and Commanders alike. Finally, Offred learns of an active resistance movement through one of her fellow Handmaids, Ofglen. Because her Commander is so high up the food chain, Ofglen asks Offred to spy on him and relay any information she can.

In this way, our protagonist is a woman caught between these various agencies. This puts Offred at an impasse throughout most of the narrative, too frightened to commit herself entirely to rebellion, too horrified at Gilead's barbarism to submit to complacency. Trapped, in other words. Offred's mental state contrasts sharply with the "rallying cry" carved in Offred's closet by the Waterford's previous Handmaid: Nolite te bastardes carborundorum, which is a sort-of Latin phrase meaning, "Don't let the bastards grind you down." This could be construed as an ironic message for the woman to leave, given that she ultimately hanged herself—in other words, her rebellious spirit was grounded out, and she no longer had the will to survive, to fight, left in her. But her suicide could also be read as proof she never gave up on the good fight, considering Ofglen also hangs herself toward the end of the novel, after her involvement with the resistance is exposed, and the Eyes are coming for her. Did Offred's predecessor kill herself for the same reason? If so, it demonstrates that she, like Ofglen, fought to the very end and ended her life on her own terms.

Whether the previous Handmaid heeded her own advice or not, Offred does not, and this is essential to Atwood's overarching commentary on the nature of patriarchal oppression of women, how men in power grind women down. Because it isn't just Offred that follows a downward trajectory of hopeless, defacto acceptance of the system. Moira, her old friend that escaped the Red Center, reappears as a sex worker in Jezebels, a hotel turned brothel set up by the Commanders of Gilead that legally allows them to behave as if there were not an evangelical theocracy operating outside the "gentleman's club" (a place Offred's Commander takes her to further his mistress designs on the supposedly sacred Handmaid). When Moira fills Offred in on what happened following her escape (she was recaptured and forced into prostitution by the regime), she insists on multiple occasions that it "isn't so bad," because she gets to drink, smoke, get high, and fool around with the other women at Jezebels as much as she wants. It's a kind of freedom for her, even though she still must have sex with any man that wants her. This admission of complacency from Moira sends Offred into a spiral of hopelessness, because she looked up to her old friend as a kind of folk hero, the one that got away, who defied the system. Without this person to look up to, Offred feels nothing but despair, and in this emotional state, she too begins to succumb, to feel as though fighting would be pointless—so much so that when she knows the black van is coming for her, she considers suicide, but is so despondent she can't really decide what way to off herself.

As she is escorted out of the house, Nick tells her to trust him and do whatever the men say. He might be indicating the black-clad soldiers are friends here to rescue her; or, they may indeed be there to escort her to her demise. Offred's final thought before the end of The Handmaid's Tale proper reads:

The van waits in the driveway, its double doors stand open. The two of them, one on either side now, take me by the elbows to help me in. Whether this is my end or a new beginning I have no way of knowing: I have given myself over into the hands of strangers, because it can't be helped. [emphasis mine]

And so I step up, into the darkness within; or else the light.

We ultimately learn, in an epilogue written as a transcript of a lecture given hundreds of years in the future, that the men did in fact rescue Offred, and that her tale was culled from a series of cassette tape recordings made while on the lam. But the fact she survived—at least, up until she reached Maine, as there is no way of knowing what happened to her after that—is inconsequential, because her resignation to either death or salvation is the key aspect of Atwood's ending. Again, consider the phrase "it can't be helped," emphasized above. In this instant, Offred recognizes she has no power in this society, that whether she lives or dies—outside of suicide, of course—is completely out of her hands. Her fate is decided by others (men, especially). Offred makes this resignation even more blatant in a passage a few pages before her narrative's conclusion:

I resign my body freely, to the use of others. They can do what they like with me. I am abject.

I feel, for the first time, their true power.

This, in effect, is how the bastards grind a woman down in this society. Not just in Gilead, but in real-life society as well, be it Reagan-era or Trump-era, or any other eras before and after. Atwood subtly points out in these moments of resignation especially, but also throughout the entire novel, that outside of forced breeding programs, Gilead isn't much different from "the before time," i.e., the United States, or any patriarchal societies. As Atwood notes in a contemporary interview,

This is a book about what happens when certain casually held attitudes about women are taken to their logical conclusions...The society in The Handmaid's Tale is a throwback to the early Puritans...[who] came to America not for religious freedom, as we were taught in grade school, but to set up a society that would be a theocracy (like Iran) ruled by religious leaders, and monolithic, that is, a society that would not tolerate dissent within itself.

Though the U.S. technically became a democracy, elements of that Puritan construct remain today, making a modern day adaptation of The Handmaid's Tale an essential reflection of our conflicted society.

We'll get to that in a moment, but first...

The Film

There is so much wrong with this film adaptation, and we'll discuss those matters, but let's first acknowledge it is a miracle the movie exists at all. Consider this passage from the book Engendering Genre: The Works of Margaret Atwood by Reingard M. Nischik:

Practically all film studios approached by [producer Daniel Wilson] declined the project. They obviously also shied away from the gendered statements and feminist concerns of the story, which shows women reduced to their biological sex and the purpose of procreation. Hollywood in the 1980s was apparently not yet ready for such a radical statement on gender politics: 'During the next two and a half years, Wilson would take the Pinter script to every studio in Hollywood, encountering a wall of ignorance, hostility, and indifference' (Teitelbaum 1990, 19). Reasons given for the refusals were, among others, 'that the film for and about women...would be lucky if it made it to video' (19).

Nischik further relates that all parties involved, including Atwood herself, were pleased with the script from Harold Pinter, but given the struggle to find a studio willing to take a risk on the project (it languished in development hell for around two years), and as director duties switched hands (from Karel Reisz, who collaborated with Pinter on The French Lieutenant's Woman, to Schlöndorff), and as producers and, apparently, members of the cast began tinkering with the script once production got underway (Pinter at this time had moved on, citing exhaustion as his reason for distancing himself from the project), the finished product was ultimately quite far removed from Pinter's vision.

Nischik further relates that all parties involved, including Atwood herself, were pleased with the script from Harold Pinter, but given the struggle to find a studio willing to take a risk on the project (it languished in development hell for around two years), and as director duties switched hands (from Karel Reisz, who collaborated with Pinter on The French Lieutenant's Woman, to Schlöndorff), and as producers and, apparently, members of the cast began tinkering with the script once production got underway (Pinter at this time had moved on, citing exhaustion as his reason for distancing himself from the project), the finished product was ultimately quite far removed from Pinter's vision.

One aspect of the original script remained intact throughout, however: the lack of voice over commentary from Offred (whose real name is revealed to be Kate in the film). Recall that The Handmaid's Tale relies on first person narration. From the get-go, all parties involved agreed the script would not rely on Kate to tell the story; Wilson commented that Pinter "brilliantly" transformed Offred's thoughts into dramatic scenes. Nischik also reprints a quote from Atwood concerning the screenplay:

Pinter's very good at writing scenes which play against the dialogue: in which what people are saying is not what's happening in the scene. That was very much required for this film. And there are so many silences in his plays, and I thought that would be necessary for this as well. There are a lot of pauses in the book.

Sadly, Schlöndorff seems not to have understood the need for these pauses, the need for certain moments to breathe, the need for characters to introspect in silence. There are several scenes that perfectly capture the horror of Gilead, like at the beginning of the film when soldiers round up women and force them into trucks, or our first glimpse of the Ceremony ritual. But these scenes never really get the chance to marinate, either for the characters or the audience. The action is nonstop, and it makes the film feel like a paint-by-numbers interpretation of Atwood's text, technically faithful in that moments and dialogue match what happens in the novel, but without any depth or real substance. According to Nischik, Schlöndorff didn't like the script or Atwood's novel very much, and set out to make The Handmaid's Tale more of a thriller suitable for American audiences—and more specifically, an erotic thriller, as Tor writer Natalie Zutter points out in her piece "Sending a Man to Do a Woman’s Job: How the 1990 Handmaid’s Tale Film Became an Erotic Thriller;" indeed, the relations between Nick and Offred are highly eroticized and wouldn't feel out of place in a late night Cinemax skin flick. Moreover, the filmmakers turn the narrative into a kind of "forbidden love" fantasy by definitively killing off Luke, Offred's husband, in the first scene, conveniently removing him from the equation and allowing the Eye/rebel and the Handmaid to fall in love (rather than the guild-ridden, desperate affair Offred and Nick share in the novel).

All these misguided changes are naturally detrimental to Offred's overall character arc. Whereas in Atwood's book, she is a woman slowly ground down by the bastards into frozen indecisiveness, in the film she comes across as abject from the very beginning, someone who never questions anything and simply goes along for whatever ride those in power choose for her, even if that ride is horrible. Zutter comments that Offred "mostly seems bemused at her circumstances, never actually anguished," save of course a few key but ultimately inconsequential moments. The writer further surmises that the addition of a voice over track from the character could have made all the difference, a point Natasha Richardson, who played Offred in the film, echoes:

Speaking as a member of an audience, I've seen voice-over and narration work very well in films a number of times, and I think it would have been helpful had it been there for The Handmaid's Tale. After all it's HER story.

Overall, there's really not very much going for this adaptation, not enough that any curious viewers should bother seeking it out. Skip it, and turn instead to the small screen...

The Series

Hulu's ongoing TV series, whether intentionally or not, addresses all the problems of Schlöndorff's film while simultaneously staying faithful to the source material and branching off into its own territory. Of particular note here is the fact that, while the show was developed for the screen by a man, Bruce Miller, over half the directors and writers are women, solving the problem Zutter noted in her Tor article: they sent women in to do a woman's job.

Hulu's ongoing TV series, whether intentionally or not, addresses all the problems of Schlöndorff's film while simultaneously staying faithful to the source material and branching off into its own territory. Of particular note here is the fact that, while the show was developed for the screen by a man, Bruce Miller, over half the directors and writers are women, solving the problem Zutter noted in her Tor article: they sent women in to do a woman's job.

There are numerous elements in the series that, on the surface, are different from Atwood's book, and while they ultimately do not change the narrative too much, there are two worth mentioning. First, Serena Joy and the Commander, Fred (Yvonne Strahovski and Joseph Fiennes, respectively) are much younger than in the novel, an important distinction for modern audiences, since it shows not only elderly couples who can no longer procreate are willing participants, if not outright architects, as the Waterfords are, of a slavery-driven theocracy.

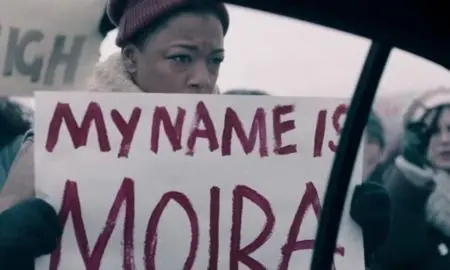

Second, the show's creators removed the outward racism of Gilead (though the hardliners of the system are still quietly racist). Showrunner Bruce Miller stated in an interview that in today's society, fertility would outweigh skin color and ethnic background; it is clear that the predominantly white upper echelon of Gilead tolerates "racial impurity" for the sake of procreation. This also allows for a more diverse cast, including Samira Wiley as Moira, O-T Fagbenle as Luke, and Amanda Brugel as Rita, the Waterford's Martha, among others.

However, these are not the only ways the series diverges from the book. Miller and company actually borrow a couple of elements from Schlöndorff's film: one, Offred—whose real name here is June—definitely becomes pregnant with Nick's child (she only suspects as such in the novel, but isn't sure), and two, she resolves not to escape Gilead without her first daughter, whom she learns is alive and living with another family somewhere nearby. But while Schlöndorff's Kate doesn't make good on this resolve (leaving Gilead when she is told to at the end of the film), June (Elizabeth Moss) makes rescuing Hannah her number one priority. And this mission relates directly to the primary distinction between June, Kate and Offred: this iteration of Atwood's character is a revolutionary.

Season one is, effectively, Atwood's novel, and so June struggles with some of the same indecisiveness and a creeping willingness to succumb to this harsh new world as her literary counterpart. But these are moments of weakness for the character, demonstrating that even the most resilient women–and June is certainly one of them—are at risk of letting the bastards grind them down. But June's resolve is strong. As Entertainment Weekly writer Jessica Derschowitz writes in her recap of the series's first episode,

[June] plans to persist. 'Someone is watching here. Someone is always watching. Nothing can change—it all has to look the same. Because I intend to survive. For her,' she says, before declaring the names of her family, a totem and a battle cry. 'Her name is Hannah. My husband was Luke. My name is June.'

A far cry from Atwood's original character, who—ostensibly out of fear, but also because it's hard to completely expunge the rules of Gilead from oneself—refuses to speak her true name, even when she is technically safe. June embraces her past and, as Derschowitz states, uses it as a "battle cry," the primary agent behind her will to survive, to return to "the time before."

However, returning things to the status quo is no easy feat, both literally in the sense that escaping is deadly and next to impossible, and figuratively, given the emotional toll living "under his eye" takes on the citizens of Gilead. This is how the series demonstrates that, no matter what, the bastards grind you down. June's resolve to rescue her daughter and escape, combined with the horrors of monthly rape and daily demoralization, causes her to become increasingly radicalized and even reckless in her actions, so that a common refrain among other characters is, "You're going to get yourself killed" (a phrase we audience members utter often as well). In this way, while this version of Atwood's character doesn't slip into indecisiveness, we see that, as Fred smugly states in season three, Gilead has changed her; she has been ground down in a way different from the novel, but ground down all the same.

And this is the crux of the series, what truly sets it apart from its predecessors. It shows us how such theocratic societies affect women (and men) in myriad ways. The Wives, particularly Serena Joy, have certain freedoms other women don't, but they're not free, and they've had to give up a tremendous amount (including the right to read and speak in public) to have what others don't. This is an aspect from Atwood's novel, yes, but the series goes further with characters like Moira and Ofglen (Alexis Bleidel), whose real name is revealed to be Emily. They both manage to escape Gilead, but their lives as refugees in Canada are in no way peachy, as they suffer from PTSD and have trouble readjusting to a freer, more embracing society. Even Janine (Madeline Brewer) plays a more significant role in the series than in the novel or the film (as portrayed by Traci Lind). While her predecessors find salvation through disassociation, removing most of her consciousness from the horrors of her station in life, in the series Janine serves to remind the haves of Gilead that even those women who buy into the system—as Janine does, albeit through brutality and psychological manipulation at the hands of Aunt Lydia (Anne Dowd)—new mothers can't so easily give away their babies, whom they bond with over a nine month period. This becomes a potentially tragic situation when Janine's natural motherly instincts mingles with her mental and emotional instability.

Thus, while in many ways the series is a different animal from Atwood's novel (and has at this point surpassed its narrative), Hulu's The Handmaid's Tale is most definitely of the same species; a modernization and continuation of the story and themes established by the author, and an excellent and worthy companion to the book (while Schlöndorff's film is nothing more than a curious historical footnote).

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com