Everyone wants to be a writer—deep down anyway. And maybe not everyone wants to tell stories on a professional or even professionally amateur level, but it is true that we're all storytellers at heart. The desire to share information, life lessons, and laughs through constructed narratives is innate to our species. We tell stories to engage with others, to flatter them, impress them, bond with them. There's a reason, for instance, couples have that "how was your day" exchange: telling each other the events of the hours they spent apart helps them feel as though they weren't apart at all. When your grandmother tells you a story of her crazy youth, you get to know a side of her you never knew she had. Storytelling is a part of humanity, and we all engage with it in some capacity every single day.

Some people are also gifted visual artists, and they tell stories by mixing and applying paint to canvas, creating objects, settings and people that communicate ideas. Even when artists paint in abstract terms, they're still transmitting their thoughts and emotions, providing the viewer a window into their subconscious. So it's no surprise to learn that some of the world's most famous painters also engaged with literary writing on some level throughout their careers, creating novels, plays, poetry, and screenplays. Let's take a look at five of those big name artists and ask the ultimate question: is their writing any good?

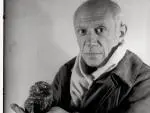

1. Pablo Picasso

He may be one of the most famous painters out there, tied only with Vincent Van Gogh—I mean, you've either got a print of Starry Night or The Old Guitar Player hanging up somewhere in your home, right? Or maybe you've got the Guernica coffee mug? Even if you're not that familiar with his broader body of work, or even his place in art history, you know who this guy is, so I'll skip the introductions and move straight on to Picasso's writings.

He may be one of the most famous painters out there, tied only with Vincent Van Gogh—I mean, you've either got a print of Starry Night or The Old Guitar Player hanging up somewhere in your home, right? Or maybe you've got the Guernica coffee mug? Even if you're not that familiar with his broader body of work, or even his place in art history, you know who this guy is, so I'll skip the introductions and move straight on to Picasso's writings.

It actually seems inevitable Picasso would gravitate toward words and stories. Three years ago the Yale University Art Gallery held a special exhibition titled Picasso and the Lure of Language, which celebrated the artist's bookish or language-based works. Covering the exhibition for the New Haven Independent, Allen Appel reports that Picasso's obsession with words stemmed largely from his association with Gertrude Stein, "that word-experimentalist par excellence," who reportedly told Picasso, "Anyone who can paint like you, Pablo, has no business hanging out with other painters," and advised him to befriend other writers instead. This Picasso did, becoming quite chummy with poet, novelist and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire. He was also seen hobnobbing with the likes of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, and James Joyce, all guests of Stein and Alice B. Toklas's salon gatherings in Paris.

These literary acquaintances no doubt inspired Picasso to try his hand at writing. In 1937 he produced The Dream and Lie of Franco, a three-sheet volume of panel sketches accompanied by prose poems—really, a comic strip, if we're being honest. Picasso followed this work up with two largely un-produceable surrealists plays, Desire Caught by the Tail (1941) and The Four Little Girls (1949), plus another volume of sketches matched with prose titled The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1959). Picasso's literary output more or less petered out after Orgaz, as he refocused his efforts on painting and sculpture.

So is Picasso Any Good?

Well, I'm no poetry expert, so let's review a sample from Picasso's The Dream and Lie of Franco:

silver bells & cockle shells & guts braided in a row

a pinky in erection not a grape & not a fig.. [sic]

casket on shoulders crammed with sausages & mouths

rage that contorts the drawing of a shadow that lashes teeth

nailed into sand the horse ripped open top to bottom in the sun..

Seems alright to me, if perhaps not very clear or concise. I mean, I understand the work was politically motivated, and I can see that in some of Picasso's word choices, but at the end of the day, what is he actually saying here?

Ditto for his dramatic work. I haven't gotten my hands on The Four Little Girls, but I have read Desire Caught by the Tail, and while it's entertaining in a WTF-is-going-on? kind of way, I'm not so sure I really 'get it.' Let's take a look at Act II, Scene II, in which all the characters are bathing together in a giant, sudsy tub (and, yes, there's a character named Big Foot):

BIG FOOT

[addressing TART]

You've got a shapely leg and a well turned navel, a slender waist and perfect tits, the ridges of your eyebrows are maddening, and your mouth is a nest of flowers, your hips a sofa, and the flap-seat of your belly a box at the bull-fights in the arenas in Nîmes, your buttocks a dish of baked beans, and your arms a sharkfin soup, and your and your bird's nest again the spiciness of a bird's nest soup. But my dear, my ducky, and my pet, I'm in a dither, in a dither, in a dither, in a dither.ONION

Old whore! Little trollope!ROUND END

My dear fellow, where do you think you are, in the house or in a brothel?THE COUSIN

If you continue, I'm not going to wash myself any more and I'm going away.TART

Where's my soap? my soap? my soap?BIG FOOT

The hussy!ONION

Yes, the hussy!

And then some dogs enter the stage and proceed to lick everyone. No, I'm not kidding.

So I suppose it's fair to say Picasso's literary work is good, if you're into that sort of thing, though he's really not breaking any new ground in the surrealist/bizarro camp. Good thing he stuck with painting.

2. Salvador Dalí

If Picasso is the Prince of Cubism, then surely Dalí is the King of Surrealism. The man produced some pretty trippy and interesting images, many of which are instantly recognizable. Like Picasso's Old Guitar Player, the 'melting clocks' from Dalí's painting The Persistence of Memory are firmly ingrained in our culture.

If Picasso is the Prince of Cubism, then surely Dalí is the King of Surrealism. The man produced some pretty trippy and interesting images, many of which are instantly recognizable. Like Picasso's Old Guitar Player, the 'melting clocks' from Dalí's painting The Persistence of Memory are firmly ingrained in our culture.

But unless you're a film nerd, you're probably not familiar with the screenplays he co-wrote with fellow Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L'Age d'Or (1930). Pixies fans take note: the song 'Debaser' references the most famous scene from Un Chien Andalou: "Got me a movie / I want you to know / Slicing up eyeballs / I want you to know." That's right, Dalí and Buñuel's 17 minute, plotless journey into pure surrealism features a POV shot of a woman's eyeball being sliced open with a razor blade. Maybe you've heard of that? L'Age d'Or, which loosely follows the exploits of two young lovers, is also famous for a single scene: the female protagonist performs felatio on a marble statue's toe. Uh huh.

But if we're really going down the rabbit hole with Dalí's literary work, let us not ignore his lone novel, Hidden Faces, published in 1944. According to Wikipedia, the novel "describes, in vividly visual terms, the intrigues and love affairs of a group of dazzling, eccentric aristocrats who, with their luxurious and extravagant lifestyle, symbolize the decadence of the 1930s." This brief GoodReads review from Sicienss provides some additional info:

The verbal Dalí is different than the visual Dalí. He doesn't write straight-forwardly surrealistically; rather, he couches the (plausible) events that occur in his fictional world in strange metaphors, in the associations that exist within the minds of his characters. I recall a particularly thrilling passage in the opening pages where he equates a woman's bare knees with the skulls of children.

In 1955, Dalí also wrote and designed an animated short for Walt Disney, titled Destino, which didn't see the light of day until 2003. He also produced a live-action short in 1975 titled Impressions of Upper Mongolia, about an expedition to find hallucinogenic mushrooms. Oh yeah, and this:

So is Dalí Any Good?

Un Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or are both considered hallmarks of the experimental film genre, and with good reason. While Picasso had to try very hard to be surreal and weird, Dalí and Buñuel were surreal and weird. Andalou in particular manages to engage and fascinate despite its lack of plot and rampant non-sequiturs (a scene featuring two men hauling, by rope, dead animal carcasses and a piano, for instance), but that's the point. The film is supposed to be anarchic and disorienting, like a night of dreams and nightmares without cohesion. Seeing this movie is no jaunty trip to the cinema. If this isn't your cup of tea, however, Destino offers more of a plot and is a real treat to watch.

As for Dalí's novel, Hidden Faces, it has a strong cult following, but I suspect this is because it was written by Salvador Dalí. I haven't picked this one up myself, but there's a webpage dedicated to nothing but quotes from the book. Here's an example:

The boat glided off and lay steeped in a kind of supernatural peace . . . a milky silence. . . . One heard a faint lapping of water against the keel, like a sound of lunar saliva. The moon-drenched kite lying against a bulwark looked like a stellar ray that had just dropped there like a sign of the Zodiac.

'Lunar saliva?' Only Dalí knows what 'lunar saliva' sounds like. Also, 'like a stellar ray that had just dropped there like a sign of the Zodiac.' I have no idea what that means. It sounds cool, though.

My final verdict: watch the short films, skip the book, unless you're in the mood for some crazy-ass, nonsensical prose—which is okay. I'm sometimes in the mood for that myself.

3. Julian Schnabel

Julian Schnabel was a prominent figure in the Neo-Expressionist movement of the late 70s/early 80s, an approach to art that blended abstract forms with roughly-depicted people and objects. Schnabel was particularly prominent in the New York City scene for his "plate paintings"—massive works adorned with broken pieces of ceramic dining ware and paint.

Julian Schnabel was a prominent figure in the Neo-Expressionist movement of the late 70s/early 80s, an approach to art that blended abstract forms with roughly-depicted people and objects. Schnabel was particularly prominent in the New York City scene for his "plate paintings"—massive works adorned with broken pieces of ceramic dining ware and paint.

Despite all his accolades as a static visual artist, however, Schnabel began pursuing narrative filmmaking. In 1996 he wrote and directed Basquiat, a biopic about friend and fellow Neo-Expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat, starring Jeffrey Wright in the titular role and featuring Dennis Hopper, Benicio Del Toro, Gary Oldman, and David Bowie as Andy Warhol. He followed up Basquiat with Before Night Falls, an adaption of Reinaldo Arenas's autobiography about persecution of homosexuals in 1970s Cuba (featuring a breakthrough performance by Javier Bardem as Arenas).

In 2007 Schnabel released The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, another adaptation of an autobiography, this one by Jean-Dominique Bauby, the one-time French Elle editor who became almost completely paralyzed after a stroke, save the use of his left eye. The film was nominated for four Academy Awards that year, including Best Director. Though Diving Bell didn't win any Oscars, it did pick up AFI's Movie of the Year award, and took home the Best Director award at Cannes. Miral, about a young girl wrapped up in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, arrived in 2010, though Schnabel had no official hand in the screenwriting process. The film wasn't as critically successful as his previous work, and boasts a 5.9 out of 10 on imdb.com.

So is Schnabel Any Good?

If the details above aren't convincing enough, then let me tell you, yes, he's actually quite good. True, much of his film work consists of adaptations, but this doesn't mean the man has no understanding of narrative fiction—if you're a good director, you have to. Schnabel's films are never terribly long—an hour and a half on average—but they feel longer, and much more dense than 90 minutes usually allows. They all sport top-notch acting and offer windows into the protagonists' minds. This is particularly true of Diving Bell, which is nothing but the world according to Bauby; the scene in which the character's right eye is sewn shut, depicted in POV, literally puts you right in the center of Bauby's horror (and serves as a visual homage to Dalí and Buñuel). It's an effective, not-for-the-squeamish scene that shows off Schnabel's talent for storytelling as communication of idea or emotion to the audience.

Also, Basquiat is one of my all-time favorite movies, since it boasts not only all the above qualities, but also one killer soundtrack.

4. Andy Warhol

You've heard about Campbell's Soup Cans, Green Coca-Cola Bottles, the first Velvet Underground LP and the concept "15 minutes of fame," but the King of Pop Art didn't just vibrantly reproduce commodities/celebrities, design album covers and coin adages. Warhol was also deeply involved in fictional endeavors, primarily films.

Let's talk about those movies. Between 1963 and roughly 1973, Warhol and his "Factory" of superstars produced hundreds of films, many shot by the white-wigged man himself. Some titles, like Kiss, Eat, and Blow-Job (all 1963) were experiments in static filmmaking, each depicting exactly what their title describes (with the exception of Blow-Job, which is actually the recipient's facial reactions to said act). Many other films were narrative-based, like Batman Dracula (1964), produced without DC Comics' permission and now long gone, but credited as being the first campy depiction of the Caped Crusader. Vinyl (1965) is loosely based on Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, predating Kubrick's decidedly more faithful adaptation by six years. There's also Blue Movie, aka Fuck (1969), about an adulterous couple alternately engaging in serious conversation and...well, the title says it all. L'Amour, about two American woman looking for rich husbands in Paris, was co-written and co-directed with longtime collaborator Paul Morrissey.

Warhol also contributed to the literary world with a, A Novel, a roman à clef starring Factory regular Ondine, aka Robert Olivio, with other Warhol clan members making clandestine appearances. The text is a verbatim transcription of several conversations between Warhol and Ondine, in which the latter regales the former with his amphetamine-fueled exploits.

Strangely, Warhol intended a, A Novel as a response to Ulysses. Certainly, it's just as difficult to understand as James Joyce's masterpiece: as I said, the novel is a verbatim transcript, full of disjointed thoughts, stories that ramble on or stop abruptly, and even typos made by the various typists Warhol employed. This is all intentional, as Guardian writer Andrew Gallix reports that Warhol wanted to produce a "bad novel." Check the win box on this one.

So, is Warhol Any Good?

Like judging Picasso's literary output, distinctions of good and bad concerning Warhol's work are subjective to the reader. If you're into weird experimental films and texts, then surely Warhol is a genius; however, if you prefer your movies and novels linear and sensical, the man was a hack. a, A Novel reminds me of Jack Kerouac's The Subterraneans, a punctuation-less speedball of a book that I couldn't finish, but the difference is, Warhol's novel was intended somewhat as a joke, and Kerouac's wasn't. Similarly, his films were never meant to be anything more than they were: experiments, funny exploits, and improvisations. If you go into either expecting pinnacles of fiction, you’ll be disappointed; however, if you place no expectations upon your reading/viewing experience, you might have a good time.

5. Yoko Ono

Yep. You might think Yoko Ono is nothing more than John Lennon’s widow and the woman responsible for The Beatles’ break-up, but like it or not, she did contribute significantly to the conceptual art movement (also, The Beatles hated each other and would have broken up anyway, regardless of Ono's presence). Her art projects are too numerous and multifaceted to really get into here, so for a decent overview check out her Wikipedia page.

Now, on to the task at hand: Ono’s writing. She created a fairytale called Invisible Flower when she was 19 years old, written in a quasi-children’s book style, featuring lines of prose matched with paintings and sketches. Not published until 2012 at the insistence of her son Sean Lennon, Invisible Flower tells a tale of hidden beauty and the one person—‘Smelty John’—who notices it (the use of the name John is mere coincidence; the piece was written several years before even meeting Lennon). Many Amazon users praise the book for the starkness of its imagery and the simplicity of its message.

In 1964, Ono published an odd little book called Grapefruit, a collection of ‘instructional poetry’ that the reader can either try at home or simply enjoy as reading material. Highfalutin-ness notwithstanding, I think humor comes into play with this book as well. Here’s an example:

TUNAFISH SANDWICH PIECE

Imagine one thousand suns in the

sky at the same time.

Let them shine for one hour.

The, let them gradually melt

into the sky.

Make one tunafish sandwich and eat.1964 Spring

Blending the fantastic with the mundane in a kind of punchline: I mean, come on, that’s funny.

Grapefruit was reissued in 1970 with about 80 more instructional pieces tacked on, and it’s still in print today. Ono hasn’t written much since that time, though she did create a piece titled My Hometown, which was used as the basis for an animated short of the same name in 2011. The poem calls for greater social awareness and pushes people to think about the world as their ‘hometown.’ Check out the short film over at Ono’s website imaginepeace.com.

So, Is Ono Any Good?

Say what you want, but I think so. It’s clear to me her writing—really, anything she’s ever laid her hands on—is meant to be whimsical. Children and adults alike can appreciate her simple messages of peace and love, and I see no reason to deride her for this. As I said before, a lot of people only recognize Ono for her spot in the Beatles-verse, but I encourage those people to dig a little deeper. I’m not a huge fan of everything she’s done, but I’m 100 percent behind her writing.

For more information on non-writers who wrote, try Cath Murphy’s column The Good, The Bad, and The Sadly Deluded: Actors Who Write. And if there are any other visual artists who took to the pen not mentioned here, shout out in the comments section.

Until next time.

About the author

Christopher Shultz writes plays and fiction. His works have appeared at The Inkwell Theatre's Playwrights' Night, and in Pseudopod, Unnerving Magazine, Apex Magazine, freeze frame flash fiction and Grievous Angel, among other places. He has also contributed columns on books and film at LitReactor, The Cinematropolis, and Tor.com. Christopher currently lives in Oklahoma City. More info at christophershultz.com