Novelizations don't get much attention these days, but for film fans they're a fond remembrance of bygone times. As a young cinephile reading the book translation of a movie's script meant not just insight into the plot, but material that was left out of the movie altogether. Still, there was a lingering feeling that the books were lesser than the movies.

Possibly it's because most aren't very good. Some novelizations are hackjobs (Jeffrey Cooper's Nightmare on Elm Street Parts 1, 2, 3: The Continuing Story, three movies plus added backstory clocking in at just 216 pages), some are workmanlike (anything by the ever-reliable Alan Dean Foster), and some transcend their origins (Orson Scott Card's The Abyss and Matthew Stover's Revenge of the Sith).

But more often than not there's a sense of unimportance because the filmmakers weren't involved. Some would point to that as a plus, such as LitReactor's own Christopher Schultz in his 2013 Article “Why Do We Read Novelizations?” In it he states: 'You're experiencing pretty much the same narrative, told with a different voice, as well as descriptions that may alter your understanding of the original “text.”'

As it turns out, however, screenwriters are always entitled to novelize their scripts. Although most turn down this opportunity, there have been a few to take a stab at it, for better or for worse. These include: Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), David Seltzer's The Omen (1976), Sylvester Stallone's Rocky II (1979) and IV (1985), Christopher Wood's The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979) and Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

By taking a look at the circumstances of each it can be determined why they contributed to an often disregarded form of literature, demonstrating their motivation, creative process and a changing culture.

![]() '2001: A Space Odyssey' by Arthur C. Clarke

'2001: A Space Odyssey' by Arthur C. Clarke

This one's a cheat, in that the novelization of 2001 wasn’t written after the script but in parallel. Concocted by director Stanley Kubrick and science fiction novelist Clarke, 2001 is the story of man’s first encounter with extraterrestrial life that seeded Earth's evolution. Astronauts venture on a mission to Jupiter but are sabotaged by a malfunctioning artificial intelligence, Hal, with only Dr. David Bowman surviving to meet his maker. Consequently he transcends his physical existence and becomes a kind of space baby god.

The project came about from Kubrick seeking out Clarke in 1964, ultimately spinning a 130-page treatment out of Clarke’s ideas and short story “The Sentinel”. Although they collaborated, it’s evident that the two split off with Kubrick completing the screenplay and Clarke the novel, all the while swapping ideas. “There are a number of differences between the book and the movie,” explains Kubrick in a 1970 interview with Joseph Gelmis collected in The Film Director as Superstar. “The novel, for example, attempts to explain things much more explicitly than the film does, which is inevitable in a verbal medium.” The movie was ultimately released on April 4, 1968 while the novel came out in June.

![]() 'The Omen' by David Seltzer

'The Omen' by David Seltzer

The Omen is the story of Damien, the Antichrist, adopted by an American Ambassador and positioned for power. The very successful Richard Donner-directed original surprisingly spawned three movie sequels (one made-for-television), a remake, two attempts at television spinoffs, and five books. The sole screenwriter of the first movie's script, Seltzer has had a varied career ranging from uncredited contributions to Willy Wonky & the Chocolate Factory to the 1990 Mel Gibson/Goldie Hawn comedy vehicle Bird on a Wire.

His novelization was released two weeks before the movie in June 1976 as a marketing promotion. According to Justin Wyatt's “From Roadshowing to Saturation Release: Majors, Independents and Marketing/Distribution Innovations” collected in Jon Lewis’s The New American Cinema, Twentieth Century-Fox attempted to copy the success of Jaws. “Based on sneak previews and extremely positive word-of-mouth” says Wyatt, the $1.50 Signet paperback “sold out in three hours in New York and Los Angeles.” Both the book and all print advertising included the provocative three 6’s inside the O of the title “to establish the movie’s identity.”

Although he did not write the sequels, penned by Joseph Howard and Gordon McGill respectively, Seltzer did retain creative control and changed substantial elements of his novel. Those changes range from things as minor as names to as major as religions. Gregory Peck's protagonist Robert Thorn becomes Jeremy Thorn, notably. An Episcopalian wedding is also changed to Catholic as there is no Episcopal Church in England, and the Etruscan Cemetery at Cerveteri is named Cimitero di Sant'Angelo, said to include “the Shrine of Techulca, the Etruscan Devil-God”. And of course elements of the backstory are fleshed out, with Tassone revealed as a Portuguese missionary recruited by a Satanist cult, and Damien actually being the third attempt at an Antichrist, the other two being in 1092 and 1710.

![]() 'Rocky II' and 'IV' by Sylvester Stallone

'Rocky II' and 'IV' by Sylvester Stallone

Sylvester Stallone was nominated for an Oscar for the first movie's screenplay, but the novelization was by noted pop author Rosalyn Drexler under the pseudonym Julian Sorel. With Rocky II, however, Stallone adapted his own work and did the same for the fourth movie (Robert E. Hoban did Rocky III). This wasn't his first book either. That honor goes to Paradise Alley, the story of three brothers from 1940s Hell's Kitchen getting involved in professional wrestling, that he actually wrote before Rocky, with both movie and book released in 1978.

An odd choice has Rocky II's novelization told mostly in first person, in the title character's unique voice, although scenes absent Rocky are in third person. There are additional characters such as Chink Webe, seemingly based on the relatively unknown fighter that went 15 rounds with Muhammad Ali, Chuck Wepner; mentions of Rocky having a criminal record; and more on Paulie's mobster activity with Gazzo. Rocky IV, meanwhile, includes fleshing out of the plot involving Apollo giving Rocky a hat and Rocky attempting to train in South Philly but deciding to head to Russia due to paparazzi.

Oddly enough, if Stallone has ever discussed his novel-writing process it isn’t evident from an online search.

![]() 'The Spy Who Loved Me' and 'Moonraker' by Christopher Wood

'The Spy Who Loved Me' and 'Moonraker' by Christopher Wood

The Spy Who Loved Me is notable for a few reasons, the first being that it was the first James Bond movie novelization. Prior to that, every movie was adapted loosely from the original novels by Ian Fleming. Roger Moore’s third outing as 007, however, barely resembled the titular novel. Touched up by several screenwriters, including Richard Maibaum, who wrote nearly every Bond script from Dr. No to Licence to Kill, and an uncredited Tom Mankiewicz, who had worked on three preceding Bonds, the ultimate credit went to Maibaum and Christopher Wood.

Because of the differences, Wood's novelization was renamed James Bond, The Spy Who Loved Me. This was the first non-Fleming Bond book in a decade at that point, the prior being Robert Markham’s Colonel Sun (1968), and Wood did the same for 1979’s Moonraker, for which he retained sole writing credit, renamed James Bond and Moonraker. The differences between The Spy Who Loved Me’s script and novelization, however, include SMERSH (the villainous, SPECTRE-inspiring organization from Fleming’s books) still being active, Bond's capture and torture by them, and Karl Stromberg renamed Sigmund Stromberg (possibly due to the controversy over the rights to the Thunderball script), amongst other things.

Moonraker, due to Wood's creative control, has no real notable differences from the movie.

Even with the attempts to make connections to Fleming’s works, however, these two aren’t considered canon. As Peter Janson-Smith, Fleming's former literary agent, described in a 2010 interview with Crime Spree Magazine, “We had no hand in that other than we told the film people that we were going to exert our legal right to handle the rights in the books.”

![]() 'Close Encounters of the Third Kind' by Steven Spielberg

'Close Encounters of the Third Kind' by Steven Spielberg

Steven Spielberg has only written one book, the novelization of his screenplay for Close Encounters of the Third Kind, although it was co-authored by Leslie Waller, a stalwart in the novelization scene who wrote Dog Day Afternoon and Hide in Plain Sight. The movie itself sprung out of Spielberg’s youth watching a meteor shower with his father in New Jersey, which led to his amateur film Firelight and a short story called "Experiences" in 1970 about a lover’s lane UFO light show. At first he considered a documentary about people that believe in UFOs, but was told that was a bad idea.

Jaws earned Spielberg an amazing amount of goodwill, allowing him to finally get Close Encounters off the ground. Although it’s suspect how much he contributed to the book, Spielberg swears in a 1977 interview with Roger Ebert that he, not a ghost writer, wrote it. The book itself has a lot of great supplemental information including some ruminations on the conspiracy theories of the 1970s, backstories and deeper insight into the Roy Neary and Lacombe characters.

The prose, however, is a bit sparse and brusque, reading more like a screenplay. No shock there. Spielberg himself commented to Ebert in the '77 interview that putting images into words can be rough, especially with that ending: “[I]t’s almost impossible to describe what happens in the last 43 minutes, anyway. I’m finding that out because I’m writing the paperback novel version of the film, and what does the movie end in? A total visual orgasm. An orgy.”

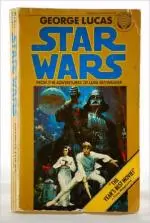

![]() Bonus: 'Star Wars' by George Lucas (Alan Dean Foster)

Bonus: 'Star Wars' by George Lucas (Alan Dean Foster)

This one is a bonus because although George Lucas's name appears on the cover of the Star Wars novelization, it was actually written by the aforementioned Alan Dean Foster. Released on November 12, 1976, Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker was the product of an earlier meeting with Lucas at Industrial Light and Magic in which Foster was hired for two projects. The second was Splinter of the Mind's Eye (1978) released as a backdoor for a low budget sequel if Star Wars tanked.

As for the novel itself, it bears many differences to the movie as the mythology and backstories hadn't been nailed down yet. Emperor Palpatine is described as rising to power only to become a tool of his political advisors, with no mention of being a Sith. Other differences are minor, including Jabba's appearance (seen in the Special Edition) as a furry, jowled alien; Red Squadron being named Blue Squadron; and Chewie getting a medal at the end.

Foster has said he doesn't mind Lucas getting the credit. “It was George’s story idea,” he explains in a 2000 interview with SFFWorld. “I was merely expanding upon it. Not having my name on the cover didn’t bother me in the least. It would be akin to a contractor demanding to have his name on a Frank Lloyd Wright house.” He consequently continues to work with the franchise to this day, having written the novelization of the latest movie, The Force Awakens.

Perhaps the golden age of the novelization has passed. There was a time when screenwriters were gaining more name recognition, especially if they were also directors, and attaching their names to the tie-in book lent it a kind of respectability. That time, however, seems connected to a very specific zeitgeist from the 1960s through the 1980s, and for whatever reason the trend has passed. Maybe it's the waning popularity of novelizations or reading in general, but for a brief window there the screenwriter managed to extend their reach and reassert a bit of control that isn't always possible in the studio system.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.

'2001: A Space Odyssey' by Arthur C. Clarke

'2001: A Space Odyssey' by Arthur C. Clarke

'The Omen' by David Seltzer

'The Omen' by David Seltzer

'Rocky II' and 'IV' by Sylvester Stallone

'Rocky II' and 'IV' by Sylvester Stallone

'The Spy Who Loved Me' and 'Moonraker' by Christopher Wood

'The Spy Who Loved Me' and 'Moonraker' by Christopher Wood

'Close Encounters of the Third Kind' by Steven Spielberg

'Close Encounters of the Third Kind' by Steven Spielberg

Bonus: 'Star Wars' by George Lucas (Alan Dean Foster)

Bonus: 'Star Wars' by George Lucas (Alan Dean Foster)