Header images via DS Stories & Magda Ehlers

You know what’s annoying? I can’t pick up a book devoted to writing craft or peruse an online literary forum without reading something about writer’s block: testimonies from those who suffer from it, a historic of famous writers who’ve lived with the condition, and tips on how it can be overcome.

So here I am, joining the fray. I’ve got an opinion on the matter, and it may alienate a number of you. At the expense of pissing off a lot of people, I think writer’s block — at least in the sense that we know it — is a myth.

Now hear me out: I’m not suggesting writers who allege to suffer from this malady are lying, or exaggerating, or concocting armchair justifications for any temporary lapses in production they may experience. I’m simply suggesting that writer’s block isn’t what most people think it is; it’s not some temporary mental wedging or a disorder that writers acquire, struggle through and somehow get over. Instead, this apocryphal condition is the result of a universal, ever-present hiccup in an otherwise complex piece of mental machinery. And you just have to get over it.

Here’s proof. Have you ever noticed that when you’re called to critique a friend or colleague’s work, you can have all the answers, a crystal-clear idea of how you’d do things differently? Most of us familiar with this activity regularly return manuscripts lashed with red ink, and Lord knows if someone writes something on the Internet we don’t like we can rise to the task of appending the offending article with paragraphs of critical response. However, have you similarly noticed that when you sit down to compose a work of fiction you’ve been mulling over for months, suddenly your brain slips off the rails and your creative output decelerates to a death rattle? And when you finally do begin writing, your mind picks these moments as an opportunity to spit out a laundry list of every nearby distraction possible?

You’re not alone. There’s a science behind this phenomenon, and it’s surprisingly simple to understand. The two aforementioned activities (critically processing information and producing our own creative ideas) involve two completely different cerebral processes, utilizing two different lobes of the brain. For most of us (the right-handed portion of the population, anyway) the left lobe is our logical side: it stores rule-abiding maxims and decodes patterns we gather empirically in the world around us. Because this side of the brain studies behaviors, it’s your most “responsible side”: it knows you’re supposed to be writing instead of obsessively cleaning the lint catcher or refilling the ice-cube trays. Then there’s the right side of the brain, which for the duration of your life has been taking personal experiences and turning them into creative works, often bubbling to the surface only when you dream. This is the celebrated part of your brain, the part that makes you uniquely “you.” It just so happens this is also the part of you that wants you to do anything but work. It doesn’t like the rules and it absolutely hates responsibilities, namely because it doesn’t know what responsibilities are. The good news here is that your creative speed-bumps aren't necessarily the result of garden-variety laziness, but are more likely due to an evolutionary flub in our collective intracranial physiology. The bad news is that the revered, creative side of your brain has the habit of acting like a petulant child — and right now it’s ruining your life.

I used to claim I suffered from writer’s block. I’d sit in front of the screen for hours without producing so much as a sentence. Nothing. Somewhere around the same time, I got a job writing for a daily newspaper. The gig required me to write two articles a day: one for the front page, another for inside filler. It didn’t matter if I was sleep-deprived, hung-over, grumpy, depressed, or just not feeling it: I had to produce. And for two very long years, I did. Needless to say, after drumming up 2,000 words of copy I was too fried to write fiction when I got home. But then it dawned on me: clearly, I can write every day if I have to, so why can’t I coach my brain to work on the stuff I actually want to write?

I used to claim I suffered from writer’s block. I’d sit in front of the screen for hours without producing so much as a sentence. Nothing. Somewhere around the same time, I got a job writing for a daily newspaper. The gig required me to write two articles a day: one for the front page, another for inside filler. It didn’t matter if I was sleep-deprived, hung-over, grumpy, depressed, or just not feeling it: I had to produce. And for two very long years, I did. Needless to say, after drumming up 2,000 words of copy I was too fried to write fiction when I got home. But then it dawned on me: clearly, I can write every day if I have to, so why can’t I coach my brain to work on the stuff I actually want to write?

That’s the challenge. You’ve got to trick the childish right side of your brain to act like the mature, domineering left. You have to convince yourself that you can write under any circumstance. And this is an exceedingly difficult task to accomplish when you don’t have the carrot of a paycheck or the Pavlovian whip of an editor balancing the scales.

So, the first step in overcoming this behavior is you have to begin seeing writing as work — because that’s what it is. There’s no denying that you’re going to run out of creative ideas sometimes, but that’s not what writer’s block purports itself to be: the process of writing encompasses much, much more than inchoate creative expressions that occur in the right side of the brain. When you find yourself faced with a lower yield of creative ideas, it doesn’t mean you can’t re-write, edit, proof, or dig up old, half-baked concepts you’ve never put to paper. In other words, if you want to write, you need to evolve your understanding of what the process entails. When one aspect of the process doesn’t seem to be responsive, switch gears and work on another. As long as your fingers can move, you can write.

There are a few tricks you can use to juke the creative process, or at least keep damage at a minimum when the creative well appears dry. Try carrying a notebook around so you can jot down ideas when they come your way. Doing this ensures you have a supply of material to tide you over when faced with creative lulls. Here’s another good exercise: try re-reading something you’ve already written. When you’re forced to logically confront scraps of creative ideas you’ve already expressed, the left side of your brain kicks the right side and tells it that it’s time to go to work. The fact is — whether we realize it or not — we are using the creative side of the brain when we a critique a friend or colleague’s writing, albeit in a somewhat limited function. Repeating this process won’t necessarily guarantee an influx of more ideas, but over time it will help you manage the creative ebbs and tides we’re all forced to deal with.

The second step involves understanding that writing is an exercise in trust. Some think writer’s block is an affliction of luxury, an indisposition reserved for those who have the time to spare. I disagree. Writer’s block is the side effect of a preconception many writers have that everything that comes off their pens should be earth-shatteringly brilliant. This is a grossly unreasonable expectation to set for yourself, and the result of a loophole concocted by right-lobe bureaucracy to prevent you from working. You’ve essentially accepted that you temporarily don’t possess the wherewithal to produce any new creative ideas, so once again you’ve given yourself permission to get up from that chair. You’ve got to reconcile with yourself that everything gets better with time. And the only way to get past those rocky beginnings and develop and improve upon your ideas is through work, work, work.

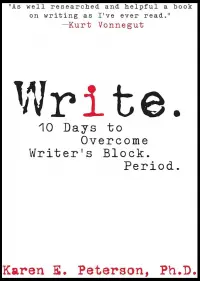

One book that discusses the right/left cranial conundrum and how it affects writer’s block (albeit from a more scientific angle than what’s offered here) is Write: 10 Days to Overcome Writers Block. Period by psychologist Karen E. Peterson, Ph.D. This is a very insightful book that sheds light on how our creative faculties work, and offers a few exercises you can perform to get out of a creative rut. Check it out!

Get Write: 10 Days to Overcome Writer's Block at Amazon

About the author

Jon Gingerich is editor of O'Dwyer's magazine in New York. His fiction has been published in literary journals such as The Oyez Review, Pleiades, Helix Magazine, as well as The New York Press, London’s Litro magazine, and many others. He currently writes about politics and media trends at www.odwyerpr.com. Jon holds an MFA in creative writing from The New School. Some of his published fiction can be found at www.jongingerich.com.