Images via Charleston Library Society

Deep in the bowels of one of the South's oldest libraries sit Brien and James, two noveau-craftsman who are trying to save the world, one book at a time.

Okay, maaaaybe that's an exaggeration, on a couple of levels. Though the Charleston Library Society's main building is as old, musty, and beautiful as any decent library should be, its "bowels," where The Bindery is situated, are surprisingly modern and sunny. Light filters in through street-level windows, through which Brien and James can watch the people of downtown Charleston pass them by. And though the tools they use and the books with which they work are of another age, Brien and James are just a couple of guys who share an abiding love of all things literary, and who want to make sure the books found within the Library's vault will be available for generations to come.

I visited them on a sun-drenched spring morning to talk hobbies, Bibles, and to learn more about the anatomy of the books we love.

The Binders

Brien Beidler and James Davis are exactly the sort of bearded fellows you might expect to be modern day artisans. Soft-spoken, warm and welcoming, their eyes light up when they learn I'm a sci-fi writer. The countertops surrounding them are littered with Tolkien paperbacks, and we spend a chunk of time discussing our favorite writers.

Then we get down to business, talking about their chosen careers, since it's not every day you meet people who spend their time repairing the oldest books in the south.

Beidler came to book binding in an organic way. In fact, it seems like everything about Beidler is organic. I'd even wager his clothes are made of organic cotton, though that's just a guess. But I mean this in the nicest of ways. He's about as down-to-earth and of the earth as it gets.

"Old books have always had a strong appeal to me," he says of his journey to the book bindery in Charleston. "In my sophomore year of high school, for an art class project we had to take apart a book, and at that point it popped into my head to learn about book binding." From then on, he's been on the straight and narrow path, volunteering with the special collections at The College of Charleston, finding a mentor, and learning on his own. When the Executive Director of the Charleston Library Society asked him to come on board, starting a new department in the library, he couldn't say no.

Davis came from the world of publishing, though conservation in all its forms has always been a part of his life. "I studied art history, and I went to Israel to study every kind of conservation. I worked with preserving scraps of parchment and pieces of the Torah with the Israel Antique Authority Archives." He worked in online publishing here in Charleston, but missed working with his hands. After a chance meeting with Beidler, he left digital publishing, and learned to sew.

The Books

The original plan for the book binders was to work almost exclusively with the books in the Charleston Library Society vault, the collection of which is vast, priceless, and incredibly eclectic. But, of course, life intervenes, and income is income. They opened up The Bindery last year to individual commissions, which piled up much more quickly than they expected. Thus, some guidelines have been laid out, such as: no more Bibles.

"Bibles are a pain," said Beidler with a bit of a smirk. This, however, isn't a dictum on religion. Rather, it's a judgment on the mass production of the bestselling book of all time. They're cheaply made, manufactured to look old and impressive, but the pages within are barely held together with tape and glue. And of course, these are the books most people want to save, seeing as how generations have used them to track family histories. It's not cost effective for Beidler and Davis to cobble these tattered books back together, so they've set the rule. No more Bibles.

Instead, they spend their time on books like the collection of childhood short stories a new grandmother had re-bound to give to her brand-new granddaughter. Beidler shows me the book with the pride of a craftsman, and it's easy to see why. The outside boards are clean and strong; the paper lining the covers is new and retro and absolutely fitting. This book will be in great shape for years to come, maybe even for the new baby to pass on to her own grandkids.

Next, Beidler and Davis conspire to show me something really cool, something so valuable they actually need to send it out to a museum-grade bindery. This is a handwritten manuscript of a history of South Carolina, penned by John Drayton. If you live in Charleston, the name Drayton is immediately familiar. There's a Drayton Hall plantation house. My daughter goes to Drayton Hall Elementary. After seeing the name on the cover, I'm already suitably impressed.

Then they open the book. Inside, you get a glimpse of the past: a handwritten manuscript from a century before the typewriter. Hand-drawn sketches beside the lithograph prints they'd become. Notes to the printer about how to lay out certain pages. To Beidler and Davis, this book is a treasure. And they don't mind passing the work along to people with even better equipment and resources. To them, simply being around the books is enough.

Anatomy Lesson

So. How does one bind (or re-bind) a book? To understand the process, you first need a brief book anatomy lesson.

In the first place, there's more than one way to skin a cat...or a book, in this case. To make a real, old-school book, it has to be sewn, for one. Let's have no discussion of the mass-market glued paperback (though we all love the smell of a brand-new paperback).

The cover options for a hand-bound book are two-fold. First, you can have a case-bound book, in which the cover is separate from the actual pages of the book. You find case-bound books everywhere there are hardcovers, as it's the slightly-cheaper way to go. These books have a distinct gap between the pages and the cover when opened. If you can stick a finger between a hardcover's cover and pages, it's likely case-bound.

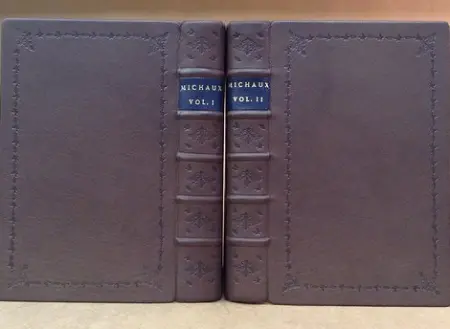

The other option is in-boards binding, in which the cover and the pages of the book truly become one entity. In this case, the pages are sewn directly into the cover, which means you can often see the book's "panty lines," or grooves where the books are sewn along the spine. This method is older, more flexible, and is arguably more durable, but is also more time-consuming and expensive. The world's oldest books are in-boards bound, and they often include those little flourishes like fancy leather wrappings and gold etchings along the grooves.

In both binding options, the actual pages of the book are separated into groupings called signatures. These are typically five to ten full pages, folded in half to be book size. Each signature is individually sewn into the spine by hand after being pre-punctured by an awl. With the addition of each signature to a book being bound, there's tugging and pressing and folding to make sure the pages sit as close and snug as possible.

The tools used to bind a book range from slightly-scary looking needles to linen thread to awls to cradles to bone folders. Beidler and Davis, true craftsman that they are, make their own tools, too. "Quality tools are way more fun to work with," says Beidler, displaying an awl he's created himself. It's gorgeous, I have to say, with a smooth wooden handle I'd swear was ergonomic. "It takes you to the next level of craftsmanship."

As Davis displays the actual sewing process ("Anyone can learn the basics," he says, pressing pages together in the cradle), Beidler steps over to offer a couple of gentle suggestions. For both of them, this will be a continual learning process, as they work together to (hopefully someday) master their art form.

So if You're Ever in the Area...

Drop by the Charleston Library Scoiety and ask to see the Book Binders. While you visit, maybe you can get them to head into the vault and show you a 400-year-old in-boards bound book written by a Pope just like they showed me. Looking at these books, touching these books...it's heady stuff, especially when you think about how long it must have taken to create them before the days of the printing press. And if you feel like you should wear gloves, well, Beidler says don't. Books are made for touching, and a naked finger is far more delicate than a gloved one.

And if you're too afraid to touch and just want to talk, and watch, well, Beidler and Davis can do that too. Take a minute and geek out over hobbits and dragons, craftsmanship and tools. Trust me: it'll be an hour you won't soon forget.

About the author

Leah Rhyne is a Jersey girl who's lived in the South so long she's lost her accent...but never her attitude. After spending most of her childhood watching movies like Star Wars, Aliens, and A Nightmare On Elm Street, and reading books like Stephen King's The Shining or It, Leah now writes horror and science-fiction. She lives with her husband, daughter, and a small menagerie of pets.