When it comes to horror stories, in my opinion, it’s crucial to build something up before you tear it down. We must create a world, show the main characters, and get readers to care before everything goes to hell. This isn’t just applicable to horror—it’s important to all genres, and any story—but today we’ll focus on horror (and tragic dark fiction) due to the unique nature, requirements, and expectations of the genre. Let’s dig in, shall we?

The Title

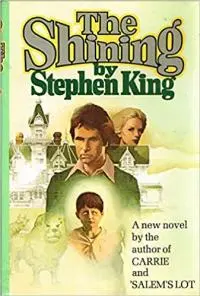

This is really the first place to set up your story. And when it comes to horror, your title can do so much. We’ll talk more about The Haunting of Hill House in a second, but the title kicks off the novel with the idea that it is going to be a haunted house story. The Shining speaks to an ability that Danny Torrance has, and plays a major role in the novel. “The Caged Bird Sings in a Darkness of Its Own Creation,” a story of mine, really hints at what is coming, right? A caged bird is trapped, yearning to be free, but the darkness in the story comes at the hands of the protagonist, who creates it (and it’s also a play on words, as there is a creator scene in the second scene). This is a great way to lay out a hint about the framework, plot, emotions, story, tropes, and genre.

Inciting Incident

I talk about this a lot in my classes, but quite often I’m still surprised that authors start their story in some random spot that has no bearing on their inciting incident. When and where you start your story is crucial to connecting to the internal and external conflicts, leading you to a resolution (with change) and a denouement that resonates. So when you are building your world, setting the stage, trotting out your main characters, and creating atmosphere, you must address the inciting incident. It’s a young Bruce Wayne seeing his parents killed in an alley; it’s the manila envelope sliding under the door and the voicemail that speaks to tragedy (in my book Disintegration); it’s a memory as a young child that Dexter has of sitting in a puddle of blood. The first line, the first paragraph, the first page, the first scene, the first chapter (if it’s a novel) should dig into this and set the story up. Is it a cautionary tale? Is it a story about vengeance? Is it a dark fantasy that ties into classic mythology? Hint at what’s coming, and then fulfill that expectation.

Setting

This is another important element of horror stories—the mood, the tone, the atmosphere, the setting. Now, maybe you’re getting that family ready to hop in a car and drive up to a hotel for the winter, so you’re not going to get to that hotel for a few pages. But why not have it looming, why not tap into the boy with “the shining” who can see something coming, why not work in the feeling of cold and isolation and separation? Sometimes you may start your story in the main location—the dark forest, the haunted house, the cult headquarters, or the abandoned ruins. Take the opening to The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met nearly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

We know from the title this is going to be a haunted house story. These first three lines are rather unsettling to me. How this horror creeps out across this family? Well, that’s the book!

Sometimes you’ll delay the location, taking a bit of time before we get to the arctic wasteland, or isolated dunes, or questionable asylum. But, whenever you get there, take those additional opportunities to ground your story in a place (or places) to help build things up before you tear it all down. Show us the limitations, give us the rules, help us see the terrain.

![]() Protagonist and Main Characters

Protagonist and Main Characters

This may be the most important aspect of setting up your story. As soon as possible, we need to understand who your protagonist is, what they want, and the exact situation at hand—both the external conflict, and the internal emotions. The external is a job for a struggling author, the money needed, and the emotions are anxiety, guilt, and fear. The external is a new ability that a boy didn’t know he had, and the growing knowledge that the hotel is haunted, and alive, the internal the fear that nobody will listen to him. The external is a husband that is losing his mind, a wife and mother trying to be dutiful, as she fears for her life, the internal that worry, building up, the fortitude needed to survive. This is of course, The Shining.

If you have more than one POV in your story or novel, then we need to get to know them all ASAP. We are going to either root for them, love them, see their dilemma, and want them to succeed OR we are going to hate them, see them as toxic, understand they are a bad person, and want them to fail. Those are two extremes and I’m simplifying here, but you get what I’m saying. And this goes for every major character in your story. If you have one POV, then we’re really telling one story, but the secondary characters also need development.

We Need to Care

As soon as possible, we need to care about your characters. This is especially true for horror. Why? Because, by the very nature of this genre, bad things are going to happen. There is going to be tension, there is going to be tragedy, there are going to be consequences, and monsters, and violence, and psychological trauma. Maybe your characters make it out the other side, maybe they don’t. But whatever happens, we have to care, or it doesn’t matter what you do to them. If we don’t care, you can give them the world, defeat the werewolves, undo the curse, and survive the torture—but if we don’t know them, go deep into who they are, then it won’t matter. Same for all of the bad things that happen—violence, possession, loss, insanity—we will be effected in a much more profound way if we feel something about them, first. And don’t forget—the opposite of love is not hate, it’s apathy. In order to hate we must first love. So keep that in mind for betrayal, for lies, for selfish acts, and shallow desires.

In Conclusion

You must build this world, develop your characters, and create immersive environments before destroying it all. We know when we read a scary story, or watch a horror film, or stream a terrifying series, that bad things are going to happen. So build this up, before you tear it down. Ask yourself this question—if a bad thing is going to happen, which will be the more intense, emotional, and memorable experience? If it happens to a stranger on the other side of the world? If it is a neighbor down the street that we like a little bit? If it is a good friend we’ve known for years? If it’s a close sibling, a twin brother, perhaps? If it’s somebody we love with all of our heart—our spouse, partner, child, or parent? The closer it gets to home, the more depth we create with large brush strokes and specific details, the more intimate the experience, the more empathy and sympathy we have—the more powerful the story. Get us to care, show us the quiet before the storm, establish a baseline, and the relationships that make up this story and it will greatly benefit the tension, mood, plot, character development, emotion, and impact. Good luck!

Get The Haunting of Hill House at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Shining at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.

Protagonist and Main Characters

Protagonist and Main Characters