I was asked recently if I had any good writing advice I might share. I’m afraid I fell back on that old wheeze, “Write what you know,” because there’s truth in it, and also because I couldn’t think of anything better. This advice, while valid, gets tricky in the case of genre writing – if you grow up quietly in a small town in Iowa, as I did, and what you love to read is mystery novels...in particular tough-guy private eye novels...how exactly do you apply that advice, anyway? I had never worked my way to Europe on a tramp steamer, let alone walked down a mean street.

In my case, I tried shifting the big-city setting of New York or Los Angeles, common to most hardboiled stories back then, to my own small home town, Muscatine, which I called Port City. (Muscatine is on a bend of the Mississippi and is nicknamed Port City.) I also made a young comics collector the secondary lead of my first book, Bait Money (1973, available in Two for the Money from Hard Case Crime), and the bank I robbed in this heist novel was the one where my wife worked. I used Port City for the first Mallory novel, too – Mallory was a hometown boy who became a mystery writer – and the first in my Quarry series, as well. Quarry is a hitman, but he is based in part on a stressed-out Vietnam vet who was a friend of mine, also from Muscatine.

That was decades ago. I still use Muscatine in the Trash ‘n’ Treasures series, co-written with my wife Barb (under the joint byline “Barbara Allan”), though we now call it “Serenity.” We also use our own interest in antiques, and the family background of Brandy Borne, the main character, derives from Barb’s own family. The next one will be out in May – ANTIQUES CHOP – if you’re interested.

So I continue to find ways to “write what I know,” despite the mystery/crime genre I’ve chosen.

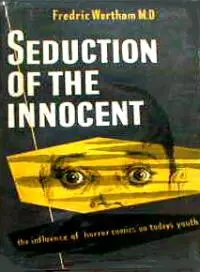

But SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT, the book we’re here to discuss (you just knew I’d get around to it), is set in Manhattan in 1954. It’s a mystery in the Golden Age style of Rex Stout or Ellery Queen, and deals with the McCarthy-era “witch hunt” into comic books, an attack led by notorious psychiatrist Dr. Frederic Wertham, author of another book titled SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT (1954), an anti-comics tome that had a lot to do with comic books getting banned and/or censored throughout America. My SEDUCTION is a novel, and Wertham’s was non-fiction...or claimed to be.

But SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT, the book we’re here to discuss (you just knew I’d get around to it), is set in Manhattan in 1954. It’s a mystery in the Golden Age style of Rex Stout or Ellery Queen, and deals with the McCarthy-era “witch hunt” into comic books, an attack led by notorious psychiatrist Dr. Frederic Wertham, author of another book titled SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT (1954), an anti-comics tome that had a lot to do with comic books getting banned and/or censored throughout America. My SEDUCTION is a novel, and Wertham’s was non-fiction...or claimed to be.

The protagonist/narrator is Jack Starr, a wry-talking (if not rye-drinking...he’s on the wagon) private detective with one client: the Starr Syndicate, distributor of newspaper comics and columns, owned and run by Jack’s sexy stepmother, Maggie, a retired stripper along the lines of Gypsy Rose Lee. Theirs is a relationship not unlike that of Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe, though with obvious differences. Archie doesn’t have any sexual fantasies about Wolfe. That we know of.

But what the hell does any of my SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT have to do with growing up in Muscatine, Iowa? Well, for a start, there’s 1954.

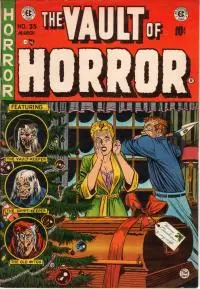

That’s the year that Dr. Wertham’s SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT was published, to much media attention. It’s also the year that the Senate held a hearing, with Wertham as its star witness, linking comic books to the spread of juvenile delinquency. It’s the year that many state legislatures banned any comic book with words like “horror” or “crime” in their titles. And it’s the year the self-governing group, the Comics Code Authority, emasculated comic books, turning a major publishing industry (millions of comics sold per month) into a shadow of its former self...and its former sales. It would not be until Marvel Comics came along in the ‘60s – with the help of the campy BATMAN TV show – that comic books became something relevant and truly successful again in American popular culture.

So where was I in 1954? You already know the answer to that – Muscatine, Iowa. I was six. I was reading comic books voraciously, many of them purchased (or traded for...two comics for one) at a nearby antiques shop across from Lincoln School, where I was in the first grade. My favorite comic book was DICK TRACY, recommended to me by my mother, who had followed that strip in a San Diego newspaper when my dad was stationed there during the Second World War. I also adored the EC horror comics, CAPTAIN MARVEL, and that other famous EC comic book, MAD.

The first sign of trouble came not from Dr. Wertham, but (though I didn’t know it at the time) DC Comics. CAPTAIN MARVEL had disappeared from newsstands. Precious few CAPTAIN MARVEL comics ever turned up at that antiques shop, either – even though that book outsold SUPERMAN, some of the time anyway. DC had leveled a charge of plagiarism against Fawcett Publications, the captain’s home. Fawcett lost the lawsuit, or maybe threw in the towel – that may have been Wertham’s doing in part, because the atmosphere Captain Marvel was flying around in was that tainted anti-comics one.

Then, as suddenly as a rotting corpse rising from its grave to seek revenge, EC was gone. And radio and TV seemed to be full of people talking about how terrible comic books were. Parents Magazine published a list of comic books every month, advising moms and dads (mostly moms) which colorful pamphlets the precious children of America might be allowed to read. Pretty much only Disney comics and LITTLE LULU made the cut. DICK TRACY was on the condemned list. Fortunately for me, my mom was not about to deny me a comic book she had recommended in the first place!

But then that terrible white stamp, with those ominous words COMICS CODE AUTHORITY, began to appear on the covers of just about every comic book. Only Dell Comics (Disney’s publisher) and CLASSICS ILLUSTRATED were able to opt out of this restrictive censoring board. Even at age six, I knew that this loathsome seal of approval meant the insides of the comic book would be pap. And I knew that Dr. Wertham was responsible. How did I know? He was everywhere in the media, talking up SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT. So I convinced my mom to take the book out of the local library for me.

I read and re-read that thing over the years, well into high school and even college. Unintentionally, it was a guide to the really interesting comic books that were out there somewhere – like “headlights” comics, as Wertham termed comic books highlighting buxom girls (you know, trash like the ARCHIE comic books, with those hussies Betty and Veronica), and of course horror and crime comic books, the true source of juvenile delinquency in America. It was illustrated in the most sensational manner possible, with the most violent or sexual panels, selected out of context of course, to make his point.

I read and re-read that thing over the years, well into high school and even college. Unintentionally, it was a guide to the really interesting comic books that were out there somewhere – like “headlights” comics, as Wertham termed comic books highlighting buxom girls (you know, trash like the ARCHIE comic books, with those hussies Betty and Veronica), and of course horror and crime comic books, the true source of juvenile delinquency in America. It was illustrated in the most sensational manner possible, with the most violent or sexual panels, selected out of context of course, to make his point.

My SEDUCTION is illustrated, too – comic art precedes every chapter, and a comic-book-style segment appears before the final chapter as a “Challenge to the Reader,” giving the audience a chance to go back over the clues and suspects. My long time collaborator on the MS. TREE comic book, Terry Beatty, has provided EC-style art. Terry is the artist of the syndicated PHANTOM Sunday strip.

Everything Wertham did and said grew out of two patently, absurdly false premises: first, that comic books were intended only for children; and second, that comic book readers were easily influenced and would imitate whatever crimes or horrors they saw depicted. He had no real research to back this up. Much of his data came from the kids he worked with at a free clinic in Harlem – an admirable pursuit of his, it must be admitted – but when he discovered that a ghetto kid read comics, Wertham declared “funny books” the reason for that child’s misbehavior. Never mind poverty or racism. Never mind an abusive parent or poor educational opportunities. In fact, Wertham allowed a major article in Collier’s magazine to use his ghetto-derived data with staged photographs of middle-class white children imitating nasty things from comic books.

That these ghetto kids read comic books was a surprise only in that they could find the dimes to buy them – almost every kid in America, in 1954, read comic books. And Wertham’s claim that comic books were only intended for, and read by, kids was nonsense. Many GIs had come home from the war accustomed to reading comic books, which were cheap, portable entertainment for combat soldiers, and user-friendly, with their combo of words and pictures, to semi-literate readers. High school kids and college kids were reading horror, crime, western and romance comic books. EC was adapting Ray Bradbury stories in their science-fiction titles. Comics as a storytelling medium had gone mainstream.

And of course Wertham was well aware that lots of adults read comic strips in the daily newspapers – many strips were intended for adult readers, particularly soap opera stuff like MARY WORTH or REX MORGAN MD, and sexually provocative features like LI’L ABNER and STEVE CANYON. But he also knew that newspapers were a powerful force that he best not take on, whereas the comic book industry was chiefly a ragtag group of publishers in New York who grew out of various low-end types of publishing, from girlie magazines and pulp magazines to ethnic newspapers and racing forms.

In a lovely coincidence, on February 19 – the day my SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT was published – the New York Times reported that a University of Illinois professor had, after studying Wertham’s papers at the Library of Congress, determined that the good doc had misrepresented and even faked his research “data.”

In my SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT, Jack and Maggie Starr – aligned with several comic book publishers, whose most popular characters are featured in Starr-syndicated comic strip versions – are dealing with the fall-out from Dr. Werner Frederick’s anti-comics screed, RAVAGE THE LAMBS. Along the way, Jack is present at the Senate hearing where the publisher of an EC-like line of horror comics has a meltdown as witness, trying to defend the good taste of his admittedly outrageous horror comic books. Central to the story is the murder of Dr. Frederick, which of course has no real-life parallel, although plenty of folks in the comic book business might well have relished having Dr. Wertham meet a grisly end. So there is no shortage of suspects.

You could even find a six-year-old suspect in Muscatine, Iowa, if you looked hard enough.

About the author

Max Allan Collins is the bestselling, award-winning author of Road to Perdition, the graphic novel that inspired the Oscar-winning movie starring Paul Newman and Tom Hanks, and of the acclaimed Nathan Heller series of historical hardboiled mysteries. Also a filmmaker himself, Collins' films include the documentary Mike Hammer's Mickey Spillane.