LURID: vivid in shocking detail; sensational, horrible in savagery or violence, or, a guide to the merits of the kind of Bad Books you never want your co-workers to know you're reading.

When we think of monsters, we tend to think of tentacled things, possessed of composite eyes, unruly teeth, scaly, slimy, controlled by a super-prescient hive mind or driven by perpetual hunger. Creepy Crawlies, in other words, as explored in an earlier Lurid. This stems from human arrogance and narcissism. We’ve positioned ourselves as the dominant species on this planet and categorize all other creatures accordingly. The less like us an animal is, the more we dislike it and categorize it as “Threat: To Be Destroyed”. On the flip side, if we can identify human qualities within an animal, we open our homes to it, feed it and shower it with chew toys.

Cats (whose cries sound like those of human infants) and dogs (who permit us to dress them in tuxedos) lucked out massively. They won the Man’s Best Friend lottery and have been reaping the benefits of domestication (regular food, medical care, a warm place to sleep) for thousands of years. In 21st century America, those benefits cost pet owners (or companion caregivers) $51 billion annually. Even in a recession, humans spend lavishly on organic food, elaborate veterinary procedures, clothing, accessories, sitting, training and walking services, even trips to pet psychics. When it comes to our beloved fur babies, there's no need, perceived or otherwise, that won't be met.

We’ve lost sight of the original reasons we had for domesticating animals (pest control, protection, food supply), and have brought them from the porch to the fireside. We elevate them to the status of favorite children. Once, dogs and cats had to earn their keep within the household. Now, we only ask that they show us affection – when it suits them to do so. They’ve shifted from functional to parasitical, draining us dry and offering nothing in return. They watch, smug, as the poor, maligned spider, willing to keep homes free from flies and fleas as a straight swap for a patch of ceiling, gets chased out with a broom.

Our furry so-called friends can be just as monstrous as, say, giant carnivorous slugs, but we choose to ignore that possibility as we cradle them in our laps and anthropomorphize their mood swings. This “ignorance is bliss’ attitude may be the direct result of toxoplasma gondii – the parasite seems to affect behavior in humans. T. gondii has infected 80% of the population, and has a measurable impact on everything from suspicion and jealousy levels to motor control. The parasite messes with our dopamine levels in order to maneuver us closer to cats – its preferred host. In other words, T. gondii is systematically turning our brains to mush so that we will nurture and protect the cat population and thus secure the parasite’s future for generations to come. Just who exactly is the dominant species here?

Thankfully, horror fiction provides us with a number of cautionary tales, some not-so subtle reminders that Fluffy has fangs. If, statistically, you are most likely to be hacked to death by a member of your own family, it stands to reason that you are at most risk of being torn to pieces by your pets. And it’s good to remember that, every once in a while. Horror also provides us with a cultural mirror, reflecting changing social attitudes to animals and the way we treat them.

Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, The Black Cat, first published in 1843, casts a long shadow. It’s a curious mix of Victorian and modern. The nameless protagonist starts out firmly in the pro-pet camp and sounds as though he would contribute a sizable chunk of that annual $51 billion if he were alive today:

I was especially fond of animals, and was indulged by my parents with a great variety of pets. With these I spent most of my time, and never was so happy as when feeding and caressing them. This peculiarity of character grew with my growth, and, in my manhood, I derived from it one of my principal sources of pleasure. To those who have cherished an affection for a faithful and sagacious dog, I need hardly be at the trouble of explaining the nature of the intensity of the gratification thus derivable. There is something in the unselfish and self-sacrificing love of a brute, which goes directly to the heart of him who has had frequent occasion to test the paltry friendship and gossamer fidelity of mere Man.

Unfortunately, his behavior patterns are altered beyond recognition, not by T. gondii but “the fiend Intemperance”. In his cups, he turns on his cherished cat, Pluto, and gouges out the unfortunate creature’s eye. Needless to say, he lives to regret this drunken act. The moral of the story is chillingly simple: don’t mess with cats, especially black cats, which are supposedly witches in disguise. They find all kinds of insidious ways to mess back:

Whenever I sat, it would crouch beneath my chair, or spring upon my knees, covering me with its loathsome caresses. If I arose to walk, it would get between my feet, and thus nearly throw me down, or, fastening its long and sharp claws in my dress, clamber, in this manner, to my breast.

Poe situates the tale in his usual sweet spot between madness and truth. Either the man is mad, and is using the animal’s normal behavior as cover for his unraveling reality, or he’s telling the truth, and the cat is deliberately seeking vengeance. Is the black cat the symbol or the cause? For Poe’s contemporary readers, additional horror lay in the idea that a lower life form was challenging the status quo. Within their worldview, humans stood atop the divinely-ordered Chain of Being, as described by naturalist William Smellie in The Philosophy of Natural History (1791):

In the chain of animals, man is unquestionably the chief or capital link, and from him all the other links descend by almost imperceptible gradations. As a highly rational animal, improved with science and arts, he is, in some measure, related to beings of a superior order, wherever they exist.

It’s terrifying that a mere cat, which exists purely to supply “unselfish and self-sacrificing love” to a human, might set out to destroy the man instead. No human, however delusional or twisted, should ever be driven by “absolute dread of the beast.” That’s unnatural. That’s not what was intended when, back at the beginning of the world, Man was given “dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” (Genesis 1:26). However it seems as though, as ever, Poe was prescient. Readers of The Black Cat learned that they shouldn’t take their position on the Chain of Being for granted, that they should start contemplating other mammals as sentient, able to seek revenge for the many, many cruelties meted out to them in the name of human dominion.

The Biblical declaration of the natural order of things was about to take a beating. A decade after Poe’s death, Darwin rattled the Chain of Being into pieces by suggesting that humans were descended from apes, not angels. His ideas met with massive cultural, religious and philosophical resistance – and still do. It’s not surprising that Creationism and climate change denial often go hand-in-hand. If you believe that humans are first and foremost amongst all creation, then they have a divine right to do what they want to the planet – all other creatures be damned. Or, they would be if they had souls.

As over-population, pollution, oil spills and Agent Orange triggered widespread environmental concern, Man vs. Nature became a popular trope, manifested in fiction that explored terrifying scientific – as opposed to supernatural - scenarios. One of these was Animal Attack, when the balance of power, tipped for so long in humans’ favor, tips back. This was already a sci-fi favorite, explored in pulp classics like The Year of The Rabbit, Russell Braddon’s 1964 satire which sets bunnies the size of German Shepherds running amok in Australia. The mutant monsters of the atomic age lacked in realism, however. It would take an infusion of blood, sex and teeth to make them truly horrific.

The man responsible for vampire-kissing the subgenre to new depths was James Herbert, a British ad agency art director. He was fascinated by the Renfield scene in Tod Browning’s Dracula when everyone’s favorite fly-muncher describes his dream of the Count:

...I could see there were thousands of rats, with their eyes blazing red, like his, only smaller. And then he held up his hand, and they all stopped, and I thought he seemed to be saying ‘Rats! Rats! Rats!’ Thousands, millions of them, all red blood, all these will I give you, if you will obey me…”

Herbert conjured this rodent army on the page in The Rats (1974), a nasty, brutish and short read that has truly earned its status as a Bad Book. The paradigm he establishes is simple and compelling: a familiar and usually harmless creature transforms into a threat, usually thanks to human interference in their habitat or gene pool, and begins a ravenous rampage. Forget the Chain of Being – the only thing humans now sit atop is a list of easy prey. Brief vignettes introduce a series of characters (often engaged in suspicious or sexual activity) who will fall victim to the creatures, their deaths presented in graphic, blood and viscera-spattered detail. Government agencies fail to admit or shoulder responsibility and it’s down to a have-a-go-hero, a regular Joe or Josephine, to save the day.

In The Rats, escaped laboratory mutants interbreed with the local sewer-dwellers and their giant progeny spill out onto the streets of East London, looking for lunch. These Rodents of Unusual Size also have a toxic bite; they don’t have to eat you to kill you, just pierce your flesh with their fangs. A young art teacher, Harris, finds himself on the front lines, as his students and neighbors are the first to fend off rat attacks. It becomes apparent that the rats are using ultrasound to communicate with one another, and are acting as a single, unified, deadly swarm. Are they unstoppable? Will they conquer London? The Human Vs. Rat struggle plays out through this book and two best-selling sequels, Lair (dealing with another outbreak, this time in Epping Forest) and Domain (after nuclear apocalypse has leveled the playing field the rats rise again), which helped establish Herbert as British horrormeister extraordinaire – he was made a Grand Master of Horror and awarded an OBE in 2010.

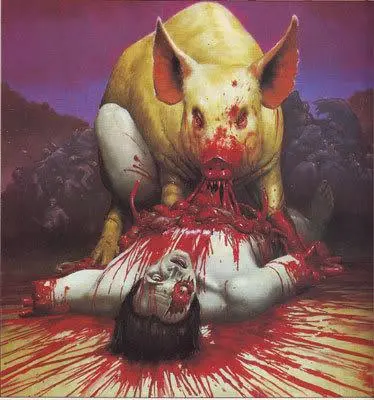

Rats actually make great pets. They’re friendly, clean, intelligent, quiet and long ago adapted to living peaceably with humans. They’re a go-to for anthropomorphic characters in children’s stories – Templeton in Charlotte’s Web, members of the Mouse and Rat Club in the Doctor Doolittle books, Nicodemus and his fellow Rats of NIMH, Ratty in Wind In The Willows, and, of course, Remy in Pixar’s Ratatouille. Yet Herbert is able to invert all those positive representations in an instant. Writers following his paradigm were able to make horror stories out of all kinds of domesticated animals throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Richard Haigh disregarded the kindly kidlit wisdom of E.B. White and Dick King-Smith and trashed pigs in The Farm, and its sequel The City. His giant, fanged Buckland White porkers tear their way through their farm of origin and then a stadium full of agricultural show-goers in a prime cut example of nature gone berserk. Herbert’s paradigm is still being used today, in books like Ricky Sides’ Claws (2011) in which chemically enhanced pet food turns cats into ‘roid-raging behemoths.

And then there are the dogs, already possessed of a fine set of fangs, but lacking the inclination to use them against their human companions. Usually. Perhaps the most notorious good pet gone bad is Cujo, Stephen King’s affable St. Bernard turned slavering hound from hell. Cujo is transformed from family favorite into terrifying threat by a literal vampire kiss, a bite on the nose from a rabid bat while he’s out hunting rabbits. As the hydrophobia takes hold of his central nervous system, all the dog’s loyalty and affection towards humans falls away. The next time his owner, ten year-old Brett, lays eyes on the pooch, he barely recognizes his faithful pet:

...that dog bore only the slightest resemblance to the muddy, matted apparition slowly materializing from the morning mist. The Saint Bernard's big, sad eyes were now reddish and stupid and lowering: more pig's eyes than dog's eyes. His coat was plated with brownish green-mud, as if he had been rolling around in the boggy place at the bottom of the meadow. His muzzle was wrinkled back in a terrible mock grin… Thick white foam dripped slowly from between Cujo’s teeth.

The afflicted animal no longer has any awareness of his position within the Chain of Being. His master’s voice is meaningless. He only hears the vampire’s howl.

…all things appeared monstrous to him now. His head clanged dully with murder. He wanted to bite and rip and tear. Part of him saw a cloudy image of him springing at The Boy, bringing him down, parting flesh with bone, drinking blood as it still pulsed, driven by a dying heart.

Although Cujo’s rabidity is perhaps enhanced through his residency of Castle Rock, a locale known for spinning catastrophe out of crisis, King sticks with natural causes for the canine killing spree. Cujo is the best argument for regular vaccination of your pets ever committed to the page.

Dog-lovers should also approach Dean Koontz’s Watchers with caution. The super-intelligent golden retriever, Einstein, is adorable, but never forget he springs from the same source as the monstrous Outsider. They were both created in a top-secret government genetic engineering lab - a wagging, grinning pup and a killing machine, derived from the same raw materials. The essential duality of canines is also explored in Bryan Alaspa’s Vicious. The Presos Canarios (125lb Canary Island dogs) Demon and Delilah fall into the killing machine category but they weren’t born that way. A lifetime of beatings from their meth-head owner, Dillon Horence, has trained them into perpetual attack mode – unfortunately for the inhabitants of remote cabins in the woods nearby who are fated to feel the sharp edge of the dogs’ teeth. Alaspa’s premise is the same as Poe’s in The Black Cat: Don’t be cruel to animals. Don’t go thinking you have dominion. Eventually, they will rise and bite back.

It seems the animals we once thought inferior have joined forces with a creature that strikes terror and admiration into our hearts, and sits somewhere between us and the fallen angels on the Chain of Being. This should come as no surprise. Pets and vampires have a lot in common besides fangs. The trouble begins when you invite them into your home – they can then wander in at out at will. Speaking of will, they have the power to sap yours. They show affection via “love” bites. They find garlic poisonous. And, unless we pay them sufficient respect and tribute, they will have our blood.

What are your favorite animal horror stories? Do you live in fear of your so-called pets? Please share your experiences in the comments below.

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .