It’s not as niche as it sounds. Chris Kelso’s Burroughs and Scotland (Beatdom Books) is an exploration of Burroughs’s rarely mentioned but highly-formative era in Scotland, jam packed with broadly hinging historical significance — just when you thought every stone of Uncle Bill had been overturned since his death in 1997. It’s an engaging hybrid Kelso’s created here: part highly-stylized personal memoir, part investigative report, part connect-the-dots whirlwind that contextualizes Burroughs's time there as crucial to his own development — not to mention our culture at large.

First, Kelso sets the scene by upending what we know about Scotland, highlighting it not just as fertile ground for transgression, but as a country pre-destined for Burroughs's arrival. His coming seemed foretold in Scot novels like Private Memoirs of a Justified Sinner (James Hogg, 1824) and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Robert Louis Stevenson, 1886). Both books chronicle the exploits of men with light and dark sides who are persecuted for merely attempting to straddle the extremes — much like Burroughs, who successfully blurred all into a highly influential literary lifestyle. On the street level, Kelso describes his own upbringing in Kilmarnock: “One look out the window gave you unforgettable images of abject horror — adolescent cadavers bouncing on the bonnet of your car, a sallow-skinned witch-cum-drug addict burning kittens alive in industrial oil drums, and freshly exhumed retirees searching for coins of a fictional romantic past.” We see the Scottish archetype he calls The Broken Boys, walking like zombies along Morren Avenue, known as Morphine Ave for the ways they break further. I asked Kelso to elaborate on the regional term he penned in the book:

“The Broken Boy concept was coined by me, but it’s a well-known phenomenon in Scotland. I’d say a majority of working-class men from ex-mining communities are brought up in a certain manner, in a certain culture where they inevitably grow into fractured and damaged adults. It’s probably not specific to Scotland, but it’s certainly prevalent — it was happening 100 years ago and it’s happening today. I teach a lot of these young boys and they’re following the exact same pattern. A glorification of alcohol and violence doesn’t help, but it’s the upbringing and environment that contributes to their broken psyche the most.”

“If ever a country was in need of a rocket up its arse, it was Scotland,” he says in the book, summing up the country’s brimming stagnation

Rocket #1 hit in 1956 in the form of serial killer Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel, who set the country on paranoid edge, the country’s imperfections rising to the surface despite its staunch traditionalist values. “Serial murder, much like taking heroin, is an act of vulgar individualism,” says Kelso.

It’s a perfect segue into Burroughs's arrival, when Rocket #2 hit Edinburgh for the turbulent International Writers Conference in 1962. Burroughs was living with Scottish novelist/editor of avant-guard literary magazine Merlin, Alexander Trocchi (who had recently been shunned for shooting up on national TV), and his doctor/dealer Andrew Boddy, tempering a transgressive fellowship that would soon rock the boat of the most important conference in Scottish literary history, one that sought to “bridge the gap between the stagnant conservatism of the 50s and the experimentation of the early 60s.” Ted Morgan would later write in his own Burroughs biography Literary Outlaw that the event was “one of those ‘the-lines-are-drawn-and-which-side-are-you-on running battles between ‘ancients’ and ‘moderns.’”

Their mere presence at the conference immediately ruffled feathers, most notably those of Hugh MacDiarmid who called the pair “cosmopolitan scum” and “vermin who should have never been invited to the conference.” He zeroed in on Burroughs in particular, condemning him as “all heroin and homosexuality,” something confrontational Burroughs could view as complimentary, an exuberant springboard that would largely prove magnetic to his work.

“It was the perfect summation of Burroughs and Trocchi and their unerring mission to emancipate human consciousness from all political and cultural control. But the conference itself was turning into a mutiny… and it was on day four of the conference, a day devoted to censorship, that Burroughs really stole the show.”

“Burroughs expanded on the consensus that all censorship is mind control… It was determined that the Ancients might espouse ‘the necessity of protecting children’ as sufficient reason for its implementation, yet the young are “already subjected to a daily barrage of words and image, much of it deliberately calculated to arouse personal desires without satisfying them.’”

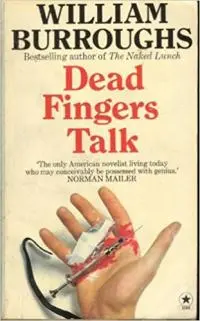

This informed intuition of how to navigate controversy would only bolster event mastermind John Calder’s decision to publish Burroughs on his imprint — it was a well-aligned decision, considering he had already published Henry Miller and Samuel Beckett. The result was Dead Fingers Talk, a shuffled-up compendium of previous works that, while not sequenced from cut-up, created an alternative narrative. “As a selector and redactor, Calder designed Dead Fingers Talk to be a kind of Burroughs ‘reader,’ a way of micro-dosing the public receptors with the heady taste of his next hard push, Naked Lunch.”

On first thought, it may seem strange the maverick author would fall prey to the mind-control cult of Scientology, but Kelso reminds us what a true dichotomy Burroughs was, who would often throw curveballs at his own devotees who still fiendishly keep track of his actions, as if the master of cut-up lived with any linear path. Although his liaison Graham Masterson described Burroughs's initial feeling towards Scientology as “extremely suspicious,” there was enough philosophical overlap to eventually draw him in. He carried heavy psychic weight, what he called the “Ugly Spirit,” the embodiment of guilt from the death of his Mother and for his own murder of his wife, so he sought therapy in many radical forms beyond intravenous drug use.

On first thought, it may seem strange the maverick author would fall prey to the mind-control cult of Scientology, but Kelso reminds us what a true dichotomy Burroughs was, who would often throw curveballs at his own devotees who still fiendishly keep track of his actions, as if the master of cut-up lived with any linear path. Although his liaison Graham Masterson described Burroughs's initial feeling towards Scientology as “extremely suspicious,” there was enough philosophical overlap to eventually draw him in. He carried heavy psychic weight, what he called the “Ugly Spirit,” the embodiment of guilt from the death of his Mother and for his own murder of his wife, so he sought therapy in many radical forms beyond intravenous drug use.

“Burroughs bought into the idea that his spiritual ailments were the result of an inflamed and experience charged Reactive Mind. In Scientology this refers to the section of the brain that is unconscious and functions on a stimulus response.”

"Years of studying Scientology resulted in his Nova Trilogy, and eventually Burroughs officially caved to the cult in Scotland. He was “audited” (their term for their evaluation through regressive “therapy”) and spent the first half of 1968 on a path to become “clear.”

But Burroughs was unnerved by strange happenings, namely to fellow Scientologist James Stewart, a salesman by trade, who was forced to undergo “Ethics Conditioning,” one of the cult’s sadistic punishments for deviation. He was found dead fifty-feet below an open window after being forced to crawl across the perilous slates of the building’s roof as penance for the final stage of his Doubt Formula. After a massive cover-up, even from his own wife, Burroughs, the living ghost himself, was spooked enough to flee back to London.

Luckily, Kelso skirts past some of the more obvious touchstones like Irving Welsh’s Trainspotting, and focuses on less household names like Scottish author/director Ewan Morrison, who helped spark Burroughs’s resurgence in the 90s. “Morrison relays that pretty much everyone who was trying to live like this in the Scottish art-scene in the 90’s saw Burroughs as a kind of God… He was the mad junkie who outlived death, enduring this realm as a kind of living ghost, surviving on a seething hatred for everything. Burroughs had a playful nihilism. He could mess you up.”

Morrison mentions three of his novels — Swung, Distance, and Menage, as having largely Burroughsian players. “My characters were looking for an escape through transgression, looking for that way out — like Burroughs said: ‘finding God in the flashbulb of orgasm’…by pushing excess to its limit and hoping something would snap, hoping some door would open. That was very much the Burroughs problem, the Gus Van Sant problem, the Cobain problem — they were asking the question ‘could you find a way out of a world with no values, by steeping yourself in transgression?’ For Cobain, it was suicide, for Van Sant there was the refuge of the aesthetic, for Burroughs the answer was to live like a ghost endlessly replaying your own escape routes.”

Read an excerpt of Burroughs and Scotland

Get Burroughs and Scotland at Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.