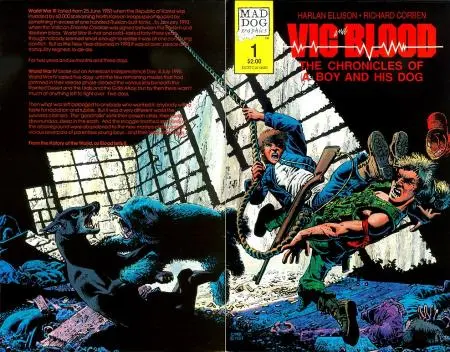

Ever since Harlan Ellison won the 1969 Nebula award for “A Boy and His Dog,” his fast-talking, fast-moving, surprisingly emotional and hugely influential post-apocalyptic ode to his real-life best friend Abu, fans have been desperate for the “whole” story. For decades, various teasers would pop up promising “Blood’s a Rover, coming soon!” The last mention I came across was in the Richard Corben illustrated collection Vic and Blood, which contained two new short stories to bookend the award-winning classic. These new pieces, “Eggsucker” and “Run, Spot, Run,” were both interesting but mostly unessential additions to the world of “A Boy and His Dog,” which itself had been expanded to novella-length for inclusion in Ellison’s The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World. But even slightly swollen, that initial nucleus which introduced these two memorable characters still felt like a perfectly proportionate and self-contained adventure. So now, with Ellison’s recent death, we have this mythical book we never thought we’d see. And, like most people (probably), I’d filed away hopes of ever seeing this book in that “unlikely/probably bullshit” part of my brain, the place where I’d kept Ellison’s promises of The Last Dangerous Visions being somewhere on the horizon, always just around the next corner.

So now that it has finally arrived, what are we to make of this thing? If “A Boy and His Dog” was perfect on its own, and if the bookends were fascinating curiosities and not much more (though "Run, Spot, Run's" bleak ending was supposedly a middle finger to fans who harassed Ellison to finish the novel), is it better to have Blood’s a Rover in this odd final incarnation? Sort of? I guess? I’m going to say, ultimately, yes. Sure, the version we get is an uncomfortable Frankenstein creation of spare parts, some long-dead, some reanimated, and some springing from the creator's brain as recently as last year, according to interviews. I've actually been reading quite a few postmortem rebuilds lately, including David Foster Wallace’s A Pale King and Michelle McNamara’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, and this is probably the most effective of the three. At least, this reassembly makes the most logical sense. Even though the final third of the book (the section titled “Blood’s a Rover”) is in screenplay form and is mostly material Ellison wrote in the late ‘70s for an abandoned NBC television series, his script directions and notes are so overwritten that you sometimes don’t miss his dense, engaging prose when the novel morphs into this format. It also helps that, because you're suddenly reading a script, you start flying though the book to the climax.

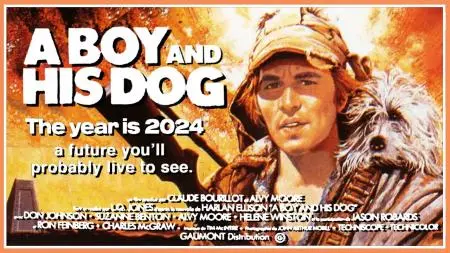

However, when I thought about it later, this ultimate form of Ellison's long-gestating project makes at least some sense because this is a book that is concerned with adaptation, in both senses of the word, so of course it would wrap up as a movie. So instead of being the famous book that never was, now you get the movie spin-off TV series that never was, and, in fact, the book is dedicated to the director of the film adaptation of “A Boy and His Dog,” L.Q. Jones (as well as Michael Moorcock). So think about this. Ellison has dedicated this strange hybrid follow-up of his original story to the creator of the film adaption, which was already its own interpretation (a decent one, too, starring a young, scrappy Don Johnson in one of his very first roles). It just feels kinda right? And the screenplay section of this book, which this reader certainly feared would be the most jarring reminder that this was a hasty assembly and not exactly what the author intended, actually fits surprisingly well into the overall vision.

So how is it? First, the good stuff. Even if the expansion of the short story, first to novella, then to kinda/sorta “novel” seemed indulgent and unnecessary, I’ve always imagined that Ellison found the idea irresistible once he pinned down such a phenomenal title. “Blood’s a Rover” is from a quote by poet A.E. Housman, referring to blood cruising the highways of our bodies (“Clay lies still, but blood's a rover…”), but also it refers to a “rover,” of course, as in a dog, and the “Blood” in this book is literally a goddamn dog, however (follow me here because I can’t), Blood is not really the "animal" in this equation because a "rover" (or "roverpak") in the A Boy and His Dog story cycle is actually a term for a special kind of human who needs a gang, so this “Blood” is not that sort of pack animal at heart, and not a "rover" at all, or even a “solo,” which is what they call the “boy” in the book, meaning we've circled all the way back to the beginning, and Blood is, and always has been, simply a dog, with all the better qualities that entails. Whew! But seriously, that’s a hell of a title, and even if James Ellroy got to that quote first to name a book after it, he didn’t give it nearly that kind of workout.

There are also some interesting bells and whistles throughout, including something a bit like that Werner Herzog daily affirmations calendar between chapters, interludes of snarky quotes from the “wit and wisdom” of Blood the dog. These are fun. Even if none of them are at the level of Ellison’s most famous zingers (“No one is entitled to their opinion. They are entitled to their informed opinion,” etc.), they still feel like they came directly from Ellison himself, which proves something we’ve always suspected to be true. He is that goddamn dog. Also, these quotes make for interesting breathers between chapters, to bridge the stories and more effectively glue them together, particularly the strange declaration of faith (out of character for the author? okay, maybe Ellison is not the goddamn dog) from the first third of the book where “Blood” says, “Without belief, we would have no reason not to be savages." Oh shit, shots fired, Richard Dawkins!

But what, if anything, is not working here? Good question. Well, here’s some of the weirder stuff; like what's going on with the copyright symbol stamped next to Ellison's name on every page? Oh, yeah, didn’t he sue The Terminator or some shit? I almost forgot. Also, I’ve always been a bit baffled by Blood talking in italics but then sometimes talking in quotes. Does this mean occasionally Ellison is deciphering his barking as words in the boy's head, or is everything in the kid’s head? I’ve always assumed every dog’s bark we hear in the real world translated as “Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!” But The Wire proved to us that this could still make for some surprisingly sophisticated sentences from our canine friends.

One of my biggest gripes was that “Eggsucker” as an opener to a novel, and the beginning of this entire story, has a lot less impact than it did as a follow-up tale. It’s sort of like Better Call Saul. Great show, but who would want to watch that as a lead-up to Breaking Bad? Okay, maybe that’s a bad example because Better Call Saul is surprisingly great on its own and “Eggsucker” needs the lifeline of the larger narrative to survive. So how about that YouTube video of Spike Lee in character as Mookie from Do the Right Thing twenty years later? It’s fascinating to see where Mookie the delivery dude is now, but you wouldn’t want to watch that clip before the events of Do the Right Thing would you, because it would rob you of some surprises later on. Okay, that example doesn’t work either because the clip doesn’t spoil the dynamic of Mookie first interacting with the owner and staff of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria. Wait, I’ve got it. How about the intro to Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, showing the two of them as babies in front of the convenience store? Now imagine that intro playing before Clerks. It doesn’t work, right? Because even though it’s a prequel of sorts, it’s starting with answers to the characters before we ask the questions. Hot damn that example was perfect! I hoped that if I just kept typing that would happen. But, yeah, the opening should always have been the opening of “A Boy and His Dog.” Jump around in time, fine, but when you have an opening as straightforward as that, why mess with perfection just for chronology’s sake?

As a story though, “Eggsucker” is decent. It’s from Blood’s POV, which is a fun switch from Vic’s narration in “A Boy and His Dog,” though Blood calling him his “pet boy” in this new opener is a bit on the nose and hinders some of the more subtle reversals of boy and beast later on. Also, did we really need to see the “burnpit screamer” scene as described in “A Boy and His Dog” fleshed out here in real time? This redundancy makes the later descriptions a bit confusing. The efficiency of the quick detail in “A Bog and His Dog,” where Vic describes the mutants as "all ooze and eyelashes” was effective because it was also sort of baffling. To find out that these screamers indeed had long, spider-like eyelashes (but crazily enough are described as having no eyelids? Huh? Magnets, how do they work?) sort of demystifies things. And it doesn’t help that, with this chronological renovation, the characters are now going to reminisce about this thing just a few pages later, making the timeline and the adventures of these characters feel even smaller and maybe more like a Facebook timeline actually, where people flashback to shit seconds after they did it.

And speaking of small, there isn’t a whole lot more going on as far as world-building that we didn’t already know in “A Boy and His Dog.” There’s villain Fellini (whose mentions usually refer to his skeevy taste for child rape and seem like inside jokes slamming the real-life director?), and there are various murderous scavengers and rivals, and the “downunder” bomb-shelter societies of squares, and maybe one or two supernatural elements; like the shrieking, radiated mutants, and some Lord of the Rings-esque giant spiders. All in all, the world of this "novel" still feels like exactly the size and scope of an excellent short story.

But when you get to the centerpiece, “A Boy and His Dog,” you quickly remember why this world has endured, and you can see the direct through-line to everything it went on to inspire, in books and film. It’s not an exaggeration to say there would be no Mad Max or its imitators without L.Q. Jones’ adaptation, and likely no Dark Tower either. But people familiar with the novella will start to notice some hiccups here with 11th-hour tweaks that have been made to the Nebula-winning manuscript. These are the sorts of little things that annoyed readers with the “uncut” version of The Stand, that tinkering and updating for no good reason. There's some repetition of lines and stories-in-stories (Blood’s gag of calling Vic “Albert” is now mentioned twice), and there's now some extra “tough guy” talk coming out of Vic’s mouth that, at best, serves no purpose, but, at worst, steps on his punch lines. For example, when Vic checks his guns with a scavenger gang (called “Our Gang,” get it?) so that he can see a movie in a theater (it’s hallowed ground, Highlander!), there’s an extra insult where he warns a goon that if there’s any rust on his weapons when the movie’s over, he’ll “wake up with a crowd around him.” Huh? What made Vic so unique in this murderous landscape is how he is one of the few holdout “solos” without a “roverpak.” I mean, it’s a minor point, and a fun insult Harlan Ellison probably used in real life, but, in the world of this book, who exactly would Vic’s "crowd" be?

Ellison has also changed Vic’s gun of choice from a “Browning” to a “Husqvarna.” And what the hell is that, you ask? Well, I Googled it and fucking Garden Weasels came up, so I have no clue. It sounds like the hat company Lou Costello worked at. This weird weapon swap possibly has something to do with Corben's beautiful cover painting, where Vic is holding a long, detailed firearm, as the foreword by editor Jason Davis explains that this cover art existed long before the book. Or maybe not? I look forward to gun nuts gently correcting me with the compassion they usually reserve for their weapons. Zing!

But one of the most disappointing new additions has to be where Vic, who has just learned that he’s been kidnapped by the Topeka “downunder” oldsters and fascists as stud service to impregnate their women, says to one of the town elders, “You first, spread your legs!” Then, regarding the townfolk’s bait girl, Quilla June, whom a smitten Vic followed back to this impotent subterranean utopia, Vic goes, “She's sure capable! Made my cock raw!” These lines aren’t out of character, of course, but they actually step on the punch line twice here because, originally, Vic simply looked around after their insemination speech, unzipped his pants, and said “Okay, line ‘em up!” Maybe I'm just nostalgic for the big laugh this original line got from young, impressionable Dave way back when.

Which leads us to the final section and the conclusion of the book, the screenplay section “Blood’s a Rover.” Admittedly, it's a crafty way to continue to stretch the material almost to the point of breaking. Though this section takes place after the events of “Run, Spot, Run,” the screenplay included here reads very much like an extended prequel of how Vic and Blood met, except the New Girl named “Spike” (Get it? Spike? Still flipping that script on who’s the people and who’s the doggies!) is the stand-in for these moments that we remember Vic flashing back to. It’s easy to imagine that this screenplay material originally began as Vic and Blood's extended origin story, a grand-slam “Eggsucker” breakfast, if you will, connecting the dots of many of the details in "A Boy and His Dog." Blood teaching Vic about the importance of reading canned goods (in all of these stories, cans of corned beef and beets are currency and litter the post-nuked landscape, unlike most apocalyptic tales where those are the first things to get swiped up) was a teachable moment alluded to in the novella, and here we get to see this new character, Spike, get the actual tutorial we’d only previously imagined.

Which leads us to the final section and the conclusion of the book, the screenplay section “Blood’s a Rover.” Admittedly, it's a crafty way to continue to stretch the material almost to the point of breaking. Though this section takes place after the events of “Run, Spot, Run,” the screenplay included here reads very much like an extended prequel of how Vic and Blood met, except the New Girl named “Spike” (Get it? Spike? Still flipping that script on who’s the people and who’s the doggies!) is the stand-in for these moments that we remember Vic flashing back to. It’s easy to imagine that this screenplay material originally began as Vic and Blood's extended origin story, a grand-slam “Eggsucker” breakfast, if you will, connecting the dots of many of the details in "A Boy and His Dog." Blood teaching Vic about the importance of reading canned goods (in all of these stories, cans of corned beef and beets are currency and litter the post-nuked landscape, unlike most apocalyptic tales where those are the first things to get swiped up) was a teachable moment alluded to in the novella, and here we get to see this new character, Spike, get the actual tutorial we’d only previously imagined.

So, as a conclusion to the entire saga, it's not entirely satisfying. Conceptualized as a TV show, it's sanitized, which gives it a sort of YA gloss and sits uncomfortably with the hard R-rating of the centerpiece. Also, despite being written in the '70s, the script has some updated groaners, like the extended siege on a Walmart (those were rare in the '70s, right?), even though more dated jokes were left alone, like the anti-climactic Richard Nixon gag that ends the book and seems like low-hanging fruit for an update these days (of course, in Ellison's alternative timeline, they were lucky enough to get nuked before Trump took office). But probably the most frustrating aspect of this final section was, for me, the new implications of the telepathic abilities that are introduced when the dog is, for the first time in this entire narrative, communicating with two people simultaneously. The backstory explains that the dogs are psychic science experiments engineered for military use, and the humans are merely receivers, so for both humans in this new love triangle to be able to "talk" to Blood at the same time seems to suggest that either the humans have these abilities, too, or the dog is less "psychic" when he bonds with individual brains and instead possibly just transmitting on a different frequency? I feel like this kind of reduces the dramatic impact of the one-on-one nature of Blood's mindmelds, as well as the "man's best friend" mantra of the stories a bit. Or, much like the dog in this book, maybe I'm overthinking things.

But the new-fangled misadventures of “A Boy and His Dog and Their New Girl Pal Spike” works way better than it has any right to, even if, just like the unnatural opening, it makes for an ending that can’t quite touch the famous last line of the original short story. The book wobbles with the new material, but it’s still worth the read. And the final storyline is not as unwelcome as, say, the long, pointless page retrofitted to the climax of the “A Boy and His Dog” novella where Vic and Quilla June bicker as they search in vain for a mortally injured Blood after they escape the town... only to circle back around to find him buried near the mineshaft where they'd originally climbed out. So what purpose does that page serve at all? Sadly, it’s probably just to get more whining out of the Quilla June character (some extra condescending “How’s your doggie?” lines, etc.) so that dumbasses today wouldn’t miss the Big Twist, as this has always been a story famous for its twist, as well as the controversy over its last line where Vic says simply, “A boy loves his dog,” which became even more famous after L.Q. Jones added his own final zinger to the movie (“Well I'd say she certainly had marvelous judgment, Albert, if not particularly good taste.”). But every section of this book ends with a zinger like that, and there are even those “wit and wisdom” zingers in between (how many times can I say “zinger”? So many zingers!), so even if these last lines don’t all land as hard as Jones' or Ellison’s standalone story, they’re still entertaining enough. They remind the reader that Blood is, above all, a sarcastic little beast shouting love and anger at the heart of America, and his spirit haunts the book right alongside the author’s.

Speaking of haunting! I’ll wrap this up on one last detail Ellison inserted into this new edition, where he, as Blood, talks about his wounds being bandaged with strips of the dead girl’s frilly blue dress. This, admittedly, does help tie in the memorable third section, “Run, Spot, Run,” as it has this sort of haunting by-proxy subplot, where the dog, due to his telepathic link with the boy, and with the help of munching on a psychedelic lizard, can actually see projections of Vic’s terrible guilt at killing the love of his life to feed her to man’s (or boy’s) best friend. This visualization of Vic’s torment is a fascinating way to sidestep the cliché of having something as goofy as Quilla June’s ghost running around, but, more importantly, it might offer me a chance at trying out one of those notorious last-line zingers.

What I’m saying is, this was a very clever way to have her ghost and eat it, too. Pow! Goodnight, Cleveland! I’ll be here all week.

Get A Boy and His Dog Collector's Edition at Amazon

About the author

David James Keaton's fiction has appeared in over 100 publications, and his first collection, Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authorities, was named the 2013 Short Story Collection of the Year by This Is Horror. His second collection of short fiction, Stealing Propeller Hats from the Dead, received a Starred Review from Publishers Weekly, who said, “Decay, both existential and physical, has never looked so good.” He is also the author of the novels The Last Projector and Pig Iron (maybe soon to be a motion picture), as well as the co-editor of the upcoming anthology Hard Sentences: Crime Fiction Inspired by Alcatraz. He teaches composition and creative writing at Santa Clara University in California.