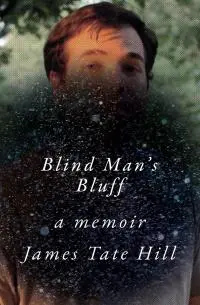

I want this discussion about Blind Man's Bluff, the new memoir by James Tate Hill, to not be about me.

What I want to do is talk about the economical storytelling, the focus on language, how no words are wasted, and the flow. I also want to talk about what it must feel like to think, if I don't figure out this writing thing, what the fuck am I going to do with my life? And I really want to talk about the machinations Hill goes through after being declared legally blind as a teenager (he's diagnosed with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy) to not only navigate a world not designed or especially empathic to his challenges, but to keep these challenges (and his diagnosis) secret from most of those around him.

The most frequent compliment heard by people with a disability is I could never do what you do, but everyone knows how to adapt. When it's cold outside, we put on a coat. When it rains, we grab an umbrella. A road ends, so we turn left, turn right, turn around. We adapt because it's all we can do when we cannot change our situation. (page 4)

We do adapt. I believe that and know it to be true. It's human. And yes, Hill has adapted as well. Yet, if it's not too mean spirited, I want to yell at the younger Hill for not asking for more help along the way. I know that makes me a dick, but that's the parent in me, which is not a comment on Hill's parents, who seem wonderful and supportive. Instead, it’s a selfish desire to yell at people whose lives might be that much easier if they asked for what they need. Hill's description alone of what he must go through to merely cross the street by himself are harrowing enough that they read more like a horror story than someone trying to get to work, school or the grocery store. Not that shopping is very easy for him either, when he can't see the labels before him.

This isn't only a parent or me being a dick thing though, it's a disability thing as well.

The other night I was teaching a class and I asked the students to break into small groups and list five strengths of good leaders and five weaknesses. One student shared that her group discussed how a bad leader fails to recognize that those reporting to him or her may have invisible illnesses or conditions. I was proud of the group for discussing this and it felt impossible to me that this would have been raised five or 10 years ago. And this despite the Americans with Disability Act being around since 1990. That's one of the things about Hill's experience, though. He may have primarily come of age since that time, but that doesn't mean what he needs or needed was in place when and where he needed it. Or at least in an easily digestible and usable format.

For a few weeks after the diagnosis, I could still bring my face close enough to the computer to read brief messages, but an acuity of 20/70 in my good eye became 20/200 and falling. Holding a magnifier against the computer screen until the pixelated words came into focus proved tedious and eventually impossible. (page 39-40)

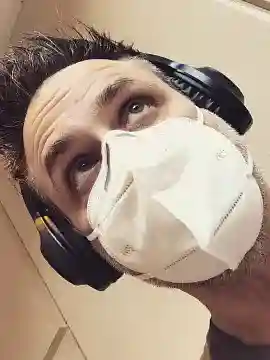

Further, not everyone is cool when you let them know what's happening with you. That's the other thing about this disability thing. During the last five years I've learned that I'm losing my hearing. It definitely fucked things up for me on my last full-time job, but I didn't know then that I was losing my hearing. That job would have been fucked anyway, but my endless confusion following instructions was confusing to me. Neither following instructions nor confusion had ever been much of a thing for me. But it was then and it remains so now. I don't mean to wholly equate my recent challenges with Hill's, except that I now have challenges I never had and I have to decide when and where to share this.

When the student raised her point in class about invisible illnesses I shared that I am hard of hearing, may miss things and may have to ask someone to repeat what they’ve said. I'm paying attention, but I don't always hear what someone says regardless, or I get stuck on a word, and then I miss everything that follows. I'm not sure there was a good chance to share this with the class sooner then I did, but I hadn't done so. I didn't tell my students about my hearing at all for the first year or so of classes until one day a student shared that she was hard of hearing, I said, "I am as well," and she said, "I know," and tapped her ear with her finger.

When the student raised her point in class about invisible illnesses I shared that I am hard of hearing, may miss things and may have to ask someone to repeat what they’ve said. I'm paying attention, but I don't always hear what someone says regardless, or I get stuck on a word, and then I miss everything that follows. I'm not sure there was a good chance to share this with the class sooner then I did, but I hadn't done so. I didn't tell my students about my hearing at all for the first year or so of classes until one day a student shared that she was hard of hearing, I said, "I am as well," and she said, "I know," and tapped her ear with her finger.

Why hadn't I shared it sooner?

I was, and at times still remain in shock that this is happening to me so young and without any explanation beyond age. It doesn't feel like a weakness to me and I sought to adapt to it as soon as I was diagnosed, but I must feel some shame even if I can't quite identify it as such.

This is also why I didn't want to make this piece about me, but am doing so anyway.

As I read Blind Man's Bluff, I wanted more for Hill. Better support and much better equipment. More compassion from others and more compassion for himself. Hill’s experiences feel so isolating. I wanted him not to be so stubborn about telling people what he was suffering through to do as well as he was, which I felt would have left him feeling less isolated. Hill may not think of himself as stubborn and he may have not felt any shame, either. I may be projecting that onto him, because I kept seeing myself on the pages before me. But Hill was alone and limited for long stretches of the story, and while again, that's not entirely my experience, when I'm at parties now or crowded meetings, sometimes I'm forced to smile instead of responding to a comment because even with my hearing aids in place I just can't understand what someone is saying. It's all noise and it can feel easier to skip these conversations entirely.

Without the benefit of eye contact, I'm never sure when drivers are waiting for me to cross. I wave them on so there's no confusion. I have never had a death wish, though a history of horns and close calls suggests otherwise. Wisdom, it turns out, is acknowledging where I cannot go without help. Asking for help means I will never be independent, but how many of us truly are? (page 231)

Hill perseveres however, and it's thrilling to read about it. In doing so, Blind Man's Bluff becomes a story about something else as well, something that has been there the whole time: Hill's desire to become a writer. Hill's struggles to get published have everything and nothing to do with his disability, and a lot to do with luck, timing and finding one's voice, their story, and a way to tell it with meaning. Which happened for Hill, as it does for some and not others. The result is Blind Man's Bluff, a beautiful, sad, frustrating story about how frustrating, sad and beautiful life can be.

Hill will continue to have challenges, but what he won't have to do is ask what happens if he cannot untangle this writing thing. He's done that in the most winning and moving fashion I can imagine. It may be cliche to call Blind Man's Bluff a triumph, but I'm no more above cliche than I am above feeling shame. It's all part of the same package and it’s all about being human.

Get Blind Man's Bluff at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Ben Tanzer is an Emmy-award winning coach, creative strategist, podcaster, writer, teacher and social worker who has been helping nonprofits, publishers, authors, small business and career changers tell their stories for 20 plus years. He is the author of the soon to be re-released short story collection Upstate and several award-winning books, including the science fiction novel Orphans and the essay collections Lost in Space: A Father's Journey There and Back Again and Be Cool - a memoir (sort of). He is also a lover of all things book, taco, Gin and street art.