Photo courtesy of the author

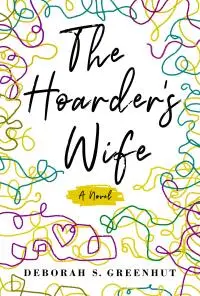

I recently had the opportunity to talk to author Deborah Greenhut about her debut novel, The Hoarder’s Wife. Drawn from her real life experiences, Greenhut weaves a tale that is at times a psychological autopsy and at others a horror novel, but is at all times a moving and lyrical exploration of resilience and survival in a uniquely complex family system. This is our conversation.

Please tell me who you are and what we need to know about your book.

My name is Deborah Greenhut, and I have loved telling stories since I could speak. At the ripe old age of 8, I fell in love with writing poetry and announced my goal of becoming a writer. My mother tried to steer me in other directions—secretary or teacher—two of the main gateways for women in the 1950s. But not a nurse, although she was one. “Too difficult a life,” she explained. My father, a dedicated Scarsdale doctor, thought women could not be doctors, despite his invention of “take your daughter to work day,” which he practiced on many days in my childhood. Although I received a lot of training in the fine arts—particularly grooming to become a concert pianist, ultimately, I traveled the teacher road, starting with teaching music in a nursery school, running all the way through graduate school and teaching communication skills to graduate students and corporate seminar participants. I’m a mother and a grandmother. That’s a main heartbeat of my autobiography. Another main artery concerns a 35-year marriage to a husband who was a hoarder who took his own life.

About the book. The novel is a work of fiction, and you will see that I drew from similar themes in my life to write it. As a writer, I don’t like to write the same thing, style, or genre twice in a row, and I’ve written several multi-genre works. When it came to finally sitting down at 68 to write the novel I had been whining about for a long time (along with 8 bazillion other English Lit majors from the 1970s), I found that I couldn’t let it be just one thing, just one genre, so I finally found a container for the story when I re-conceived it as a journal within a novel…and a lot of music threading everything. It may be that there are, "Too many notes,” to borrow a phrase from Count Orsini-Rosenberg, the emperor’s musical advisor, in Forman’s “Amadeus.” I hope that, as Mozart replied, “there are just as many notes…as are required.” It took me about two years to adapt my notes from the preceding 30 to write the novel. Thanks, in part to the pandemic, I was able to focus.

Edward Albee often said that he wrote to find out what he was thinking, and I am driven to do that, too. Until the words start flowing—many words, I’m not sure. So, despite good advice about conciseness, I almost never do anything “nice and easy," following to the gospel of Tina Turner, as voiced in the preamble to John Fogerty’s song, "Rolling on the River (Proud Mary)." And, yes, the title character, Grace, the hoarder's wife, is a lapsed musician struggling to make her music and her life work.

The book depicts a lapsing Jewish-American family because it’s what I know, but I also believe that a reader whose family struggles with mental disorders among its members will find common ground with my story, despite any specifics of culture. Fair warning: there was a lot of sadness on the way to a clean house.

There are so many interesting notes to follow-up on here, but starting with "you will see that I drew from similar themes in my life to write it," I'm curious how you decided which elements of your life to include and which not to include?

Writing this book was a long, unwieldy process. It began as a memoir that led me down several rabbit holes to non-redemptive, wooden narratives, bereft of kindness. I was angry and grieving, but I knew that wasn’t my final perspective on my former husband’s suicide. When things happen, I do research, and for some time, suicide had been topic A. I had also read widely about hoarding, and I noticed that there seemed to be little systems thinking about how a hoarder’s family coped. Forums and chat rooms tell most of the story of what it’s like to confront the hoard daily while TV shows and self-help books rely on the platitudes of patience and tolerance in the face of crumbling relationships and anguish. People really did tell me to forget the last twenty years of our marriage and start over, but they offered us no advice on how to do that. All that interested me. During my marriage, I could not find an answer to the question of why I stayed in that mess, and in the end, it wasn’t the hoard that expelled me; it was my husband’s anger. Focusing on the hoard, which the memoir did, was not such a compelling story. Once you have described a mess, the point is made—to keep making that over and over without insights did not offer any new meaning. Why did I “let” it happen?

So, after I wrote the memoir, I realized I did not yet have an answer to that question, and I needed to find it. Although I focused on writing and teaching all my life, I did have 12 years of training as a concert pianist, so I found it enjoyable to think about Grace as a musician—a life I knew something about but decided against. I also liked the intangible quality of music—a performance art you could not hold in your hand. Unlike writing—you can hold books in your hands and even collect them—performed music is ethereal; the sound is quite temporary. The sheet music is not the thing. So, I thought it would create a good frame for Grace’s understanding of herself and assist in describing the difference between Luddy’s personality and hers. This duality helped me define distinct characters. Because she focused on intangibles, there was always room for more of Luddy’s tangibles. Life is not that neat, of course, but literature allows and requires a more artful structure, so that was my idea in organizing the book. Grace stayed because she loved Luddy; Luddy thrived on her tolerance. Luddy studied why tangible things failed, or broke; Grace focused on how to put intangibles (sounds, notes, experiences) together. They were two halves of a whole, but their interlocking pieces stopped fitting eventually. When I was editing my story, I could go back to that duality to check whether I was writing what I meant to write or had ridden off the rails somewhere. It was a good touchstone. Life is seldom as neat as a novel can be, and I wanted to expose the muddiness but with clarity. The hoard could get boring, but the people around it could remain fascinating.

Once I changed the wife’s profession, that liberated me to make other decisions. I do not have a sister; I created one for Grace: Lisa. Although she plays a small part in the narrative, that decision seemed to liberate me to explore and devise novel experiences to explain Grace’s history and her devotion to Luddy and to remove the story some distance from my memoir.

Last, the memoir traveled through some unkind territory, and I wanted my character to emerge with her kindness intact. I didn’t want her to be broken by the grief load. I wrote this novel to set myself free.

Yeah. I think it’s starting to work.

I'm struck by the phrase "Life is not that neat, of course, but literature allows and actually requires a more artful structure." People write their lives for all kinds of reasons. You wrote yours to understand why anyone stays in such a relationship. You also wrote it to set yourself free. Having written it, can you visualize a different version of the book where the answers aren't as clear or where you had not set yourself free, and if so, where would that leave you now?

Yes, I can visualize it. And I think you mean the question to refer to both my life and my writing. I lived in a stuck situation for so long. Years ago, I was trying to write a play about it, but finally, that work didn’t seem to do justice to the characters, or to me or to my spouse, who was a deeply troubled person and not the monster I was creating in that play. It was my writing, but I could not make the woman leave the house; nor could I find a credible way to represent the man. My play lab colleagues suffered through multiple versions of that script, and my fellow writers wanted to help me to make the husband’s character believable, but my inner terror about what was happening in my home made him a monster, and they doubted that his wife—or anyone—would stay with him. Although I knew that someone—many people, in fact—would stay, the lab wanted a different through line for the couple. I kept writing with the intention of making her leave, but I wasn’t going anywhere, and, in the last often-revised scene, neither was she. A cautionary tale. I don’t always listen to what my writing is trying to tell me!

Another thing that comes to mind has to do with a woefully dysfunctional couple who were in the news years ago—1987, to be exact. There was a horrible man named Joel Steinberg, who abused and battered his illegally adopted children and his wife, Hedda Nusbaum, who either lost or forfeited her power to do anything about it. One child died due to a neglected wound from Steinberg coupled with Nussbaum’s inability to act. The couple lived in a filthy apartment, and they were professionals in New York who became addicted to crack and then descended into true evil. Steinberg was an attorney, and Nussbaum was a book editor for Random House. It seemed unbelievable, but I knew from fixing on this horrible story, that it could happen to anyone. Steinberg’s murder trial was the first one to be televised. That these sick people were also Jews violated so many principles for me. At the time of their crimes, our home was still functioning, but the spectacle stayed with me.

The day I made the decision to finally leave my home, I kept replaying the vacant eyes of Hedda Nussbaum in my head, thinking that my life could follow a similar path to a complete loss of my own agency if I stayed. I couldn’t overlook or endure my spouse’s anger, which had found a new and scary expression that day, and I could no longer ignore or tolerate the filthy hoard and his inability to accept help to overcome it. The meds of that time for his mental disorders were a mixed blessing of experiments that created new problems while turning the volume down on the old ones, and they relied inexplicably on his unpredictable ability to remember them.

While we were both high-functioning professionals, our self-respect had evaporated, love was weary, and I wanted my life and a decent living space back.

I remember the story of Hedda Nussbaum well. It was heartbreaking and scary to me then, and remains so in your retelling of it. As I read and re-read your answer, I thought about how for so many of us there is a sense of horror that accompanies feeling stuck in the ways you describe, which lead me to think about how in its way, your book can be read like a horror story as well. How do you respond to that reaction (and even the self-serving nature of the question itself)?

There are indeed visual moments of horror in this novel in addition to those emotional ones—an attic scene, a gruesome death—I don’t want to mention a lot of spoilers here! I have often written about difficult subjects and terror—that’s where a lot of dramatic conflict resides in my literary imagination. And isn’t it tempting to think about a horror film with a musical score performed by Kronos Quartet? Some years ago, I watched their live performance of Philip Glass’s sensual Dracula score for the 1931 film. Chilling. Joan Didion in The White Album spoke about writers learning to “freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

Yes, “learning to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria” of our lives feels like exactly what we do as writers, and now we have some thoughts on why we do so. My question then is should we and/or do you believe we have a choice in the matter?

Spitballing here…One author’s shoulds likely differ from another’s, so I won’t presume to represent everyone in this answer. Chez moi, while I feel I have a choice, I believe I choose to freeze those moments because, for me, the act of writing begins as a runaway word train in my mind after I see an image of what I’m thinking about. I will try to unpack that because my feeling of being “in the zone” as a writer consists of multisensory, sometimes synesthetic images. See, there’s that train. So, first, I’ll see something—a picture of a word. If I’m inspired, I will hear that train as a voice or music, so seeing and hearing come first. To slow it down, so I can understand what I’ve conjured up and tell it back, I will add the other three senses. If I don’t “freeze” it, what I write ends up being less accessible to other people. In my compositional state, I think I act a bit like a Dracula (there’s your phantasmagoria!) sucking the life out of words—or maybe it’s more like Giacometti, squeezing the life out of the material as he did with his sculpture—until I run out of fuel and must begin again. Typically, I do a lot of revision until I feel drained of possibilities. Sometimes, this over-thinking process is dreadful. I’m not sure I answered your question, which now seems more philosophical than technical, but that’s what came up when I tried to lift the curtain.

Technical, philosophical, I want it all, so yes, asked and answered. As I read your answer I started thinking about how much I’ve been trying to get into your head as a writer, and people may also be interested in what it’s like to be more in the head of someone who lived as you did. You’ve already touched on this, but what do you think people understand about hoarding and what do you think they get terribly wrong?

I see. I wrote the book, in part, to explain to myself how I could stay with a hoarder. Perhaps that makes me a good proxy for people’s understanding and misconceptions of hoarding, so here’s what I think as I stand at the far end of the trail. First, it’s difficult to understand hoarding in any rational way. Hoarding, as I understand and have experienced it, has little to do with thought, and everything to do with an insatiable need for emotional comfort. Resumé-wise, my family appears to be a rational organism, with nearly a dozen post-graduate degrees among parents and children. On paper, we look like Vulcans. In real life, there was a lot of denial and anxiety going on among the parents and probably among the children. It can happen in any family. My capacity to deny sent me on a near-decade quest to find a big enough house for all our stuff. I deluded myself that lack of space was the problem. But while my husband humored me by attending these realty adventures, he never intended to move because the house he was destroying was part of his hoard. It took me a long time to get that.

As far as what people understand about hoarding—they will say they know it’s “hard,” but they do not know how hard it is to stop.

From the outside looking in, we all think we can fix hoarders. We use phrases like, “If you’d just (fill in the blank with your organizing tip),” or “If you could only (explain what you want hoarders to stop or start doing).” In the moment of the conversation, the hoarding person may agree with those suggestions to get the talk over with fast or fight back in fear. My husband told me his open piles of stuff were no different from my filing cabinets. I had to agree somewhat cynically that there was a grain of truth in his comparison, though I noticed that when I discarded anything of my own, he brought it back into the house.

Thanks to TV, we have some pretty solid visual images of what hoarders and their partners look and sound like, with partners ranging from resigned to infuriated. Hoarders are typically defensive and easily provoked by other people’s demands for clean-up or sneaky discarding of valuables. That the hoard is a security blanket of sorts is easy for non-hoarders to overlook in their disgust and disbelief. Viewers agree that these accumulations must be cleaned up, but they do not understand how difficult it’s going to be for that to happen. People are slow to accept the mental disorder component of hoarding.

Hoarders have to (want to) fix themselves if it’s going to happen, and even then, it will be difficult and sometimes only temporary.

Hoarders have to (want to) fix themselves if it’s going to happen, and even then, it will be difficult and sometimes only temporary.

In my experience, what’s been ignored by both professionals and laypeople (non-hoarders) is that if there’s a relationship that includes a hoarder, there’s another affected person. (n.b., Some hoarders have been abandoned by partners and families who have been unable to effect change.) Their trauma from living with the hoard and hoarder can be severe, and these partners may have brought their own trauma(s) to the table, too. So, it’s a complex family system that presents, with the hoarder upstaging everyone else in therapy theater. While the hoarder gets the meds and the therapy, the spouse and children may be offered a healthy dose of amnesia and the advice to tiptoe around the hoarder. A secondary family therapist might be working at odds with the hoarder’s therapist about boundaries and acceptable behaviors. There might not be a third-party case manager to supervise these conflicts.

Writing this book helped me to look back, at least fictionally, at some survival and crisis management skills I had acquired in my own life—which operated both to my advantage, in that I could “power through” difficulties at the time, but also to my disadvantage, as I can sustain a huge volume of compassion fatigue before I realize I am being harmed by it. I have always believed that people could change. My life taught me that they will not change if they do not want to, and you may not realize it before you have devoted a lifetime to a love of lost people and causes. Triage was never meant to be a long-term life strategy.

Lists of behavioral dos and don’ts given by well-meaning CBT therapists seem to invite more suffering and guilt than healing for the other person(s) in the relationship who might be written off as (an) enabler or (a) thwarter. I got the suggestion to journal my thoughts. [Insert wry smile here.] I’m sure it’s a great suggestion, but my voluminous notes from the time did not do much to heal me. Love doesn’t just disappear when someone suffers mental illness, but the wells of patience and kindness can run dry and be replaced by bitterness and frustration. I wish there had been a professional way to value each of us in that struggle. My own spouse was competitive about a race to the bottom of self-esteem. I got caught up in it because I felt like a failure as a spouse, and I couldn’t compel myself to leave until he reached a low enough level where I finally knew I couldn’t join him. Am I saying that both of us were damaged before we met? Yes. I don’t know if that’s a pre-condition, but I do know that the wails of relatives and friends sound remarkably similar in chatrooms and forums even if they run on a spectrum of determination and hope. If you stay for a long time, the project is about two wounded people, not one.

People don’t seem to understand the gut-level isolation of the hoarder house. In my case, a vague shadow of suicidal despair was always present, and I didn’t know how to deal with it. I knew I was living with a depressed person long before I perceived the structural hoarding. But there was always that chicken and egg question of what came first—the anxiety or the coping mechanism. Our extended families often ascribed the hoarding to laziness or bad behavior—both my own and my hoarding spouse’s. That feeling of failure with family adds to the growing emotional load of shame and low self-esteem, and the hoarding escalates to assuage it. Mission unaccomplished.

In the 1970s, the cause of hoarding was less well understood and construed as faulty decision-making. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) was thought to be the answer. By the 1990s, researchers understood it to be comorbid with attention deficit and other disorders and began to look at executive skills (frontal lobe) deficits. More recently, traumatic experiences, such as divorce, assault, and displacement, are cited by some as top causes of hoarding behavior, and, with this shift in the balance of understanding, I think there has been a shift in treatment modalities to include some psychotherapy to address the anxiety. This is my limited layperson’s quick-take summary of what I saw and have read. Who knows if we really understand it with any precision? I don’t mean it’s hopeless, but it is more complicated than people understand.

I think that any solution that does not include the family when there is one is probably not going to succeed, because without a buy-in for the new behaviors the person wants to try, the family may find it difficult to accept and could be reluctant to travel in a new direction. It seemed odd to me that the non-hoarders in our story had to become the “bad guys” so that the hoarder could heal. There was so much shame among us after years of hiding our home. Maybe that wasn’t what was meant to happen, but it did. I didn’t, and still don’t, believe that you can create self-esteem for someone else. While we were good at tiptoeing around my husband’s concentration issues, we had no support for our struggle to do that. I take heart from the appearance of family centers for ADHD treatment, and I hope they can provide more systems thinking to help everyone. I continue to regret what I asked of my wonderful children and marvel at their coping skills in the face of so much denial in both of their parents. Their forgiveness of us is the gift of a lifetime. Look at that—you got inside my heart, too.

I wasn’t consciously looking to get into your heart, though I much better appreciate how complex all this is. I’m reminded, as I always am, about the impact shame has on people’s lives and how much it can twist and contort things. And so, I also appreciate all you’ve shared here. I suppose my nearly final question is what comes next after you’ve written a book such as this, as an author, a creative and a human?

I am never not writing something, and there are several open projects on my desk. There are one or two love stories I want to write—one prose and one a series of poems; a surreal play that I need to make accessible to other people; a children’s picture book on Thailand that I need to finish; and there’s a dance documentary I need to complete. I’m enjoying this “dabbling moment” of roaming around in my notes to find the next true north on my compass. When I reread what I wrote, I noticed that “want” came up only once amid the sea of “need.” Maybe that’s a clue? After all this isolation, I can’t wait to get back outside with my camera. Last, as a human, I’d like help create more family memories to make up for the time we lost during the pandemic.

And my truly final question is what did I overlook and/or what do you wish I would have asked you?

This interview felt so thorough, but since you asked me to think about it: You might have asked me if I had any agenda apart from the passion of storytelling in publishing this book. I hope that I can help someone—that there’s a reader out there who needs the push to make a change for a better life, and a story might help to make that happen. Thank you for asking!

Get The Hoarder's Wife at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Ben Tanzer is an Emmy-award winning coach, creative strategist, podcaster, writer, teacher and social worker who has been helping nonprofits, publishers, authors, small business and career changers tell their stories for 20 plus years. He is the author of the soon to be re-released short story collection Upstate and several award-winning books, including the science fiction novel Orphans and the essay collections Lost in Space: A Father's Journey There and Back Again and Be Cool - a memoir (sort of). He is also a lover of all things book, taco, Gin and street art.