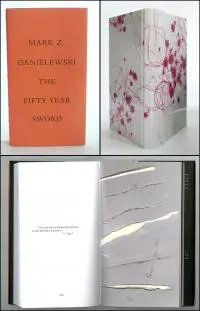

Midnight approaches on Halloween. Five orphans and an East Texas seamstress at a birthday party sit, captivated by a Story Teller’s tale, and the long, mysterious black box he's set before them. But they're also being held captive by the malicious fate the Story Teller foretells: The Fifty Year Sword. This story, retold here by five narrators, each designated by a different autumnal-colored set of quotations marks, tells of the Story Teller and how he became inevitably linked to his eponymous sword, and how that sword becomes entwined with the fate of each listener (and maybe reader) of the tale. This strange novella, itself a thing of urban legend-level hearsay for years now—the book was first published on Halloween 2005, in the Netherlands, with only 1,000 copies printed in English—is a new spin on Poe-esque ghost stories, and is being delivered in its new form full of beautiful (and sometimes beautifully grotesque) stitched illustrations, the colors of Halloween's season, and typography that actively follows what happens within the story. And so The Fifty Year Sword continues with Mark Z. Danielewski’s explorations of the art of visual storytelling, and what's on the line when it comes time to tell (or re-tell) a story.

The liminality of Halloween, the exact second midnight strikes, the moment of birth and the moment of death, each play a strong role in this story—they all create a sense of purgatory, almost. Do you feel there's a certain liminality to storytelling itself, how it exists between the teller and listener/reader?

As an undergraduate, I recall writing a paper on Dante’s Divine Comedy. Two elemental parts of that inquiry still stick with me: nescience and the leap. How when we encounter the unknown, we must somehow manage to leap beyond it or at least into it—whether it proves a heaven, purgatory, or some forever-perdition; our delights, doubts, or fears. (And heaven forbid we don’t leap because one’s thing for sure: heaven is forbidden if we freeze. Of course, so is hell, but does joy ever find those who seldom risk despair?)

What has gone unchanged since that time of teenage scrawlings—taught to me, and I mean this literally, by Dante himself, who was taught by Virgil, for yes, [mustering best pompous voice] so are we all taught who read—is an understanding that the author must first and foremost serve as a guide leading the reader to tread beyond the limits of her or his certainty, to generously and responsibly take each (because the reader is never a Them) to the threshold of the imagination and encourage a leap not to the stars or even beyond the stars but beyond the compass points of personal belief.

Aside from the sort of lexicon of sword/sewing/stabbing wordplay that makes up so much of T50YS, you also use many, I guess what we could call, solecistic-puns. Besides being a lot of fun to read, is that part of what the five narrators’ particular account of this story is playing with: the potential dangers that lie within a "misspoken" string of words, or a "mishearing/misinterpretation"?

Aside from the sort of lexicon of sword/sewing/stabbing wordplay that makes up so much of T50YS, you also use many, I guess what we could call, solecistic-puns. Besides being a lot of fun to read, is that part of what the five narrators’ particular account of this story is playing with: the potential dangers that lie within a "misspoken" string of words, or a "mishearing/misinterpretation"?

I’m glad you brought up the matter of what is incorrect; what is in breach; what you so accurately and pointedly (if you’ll forgive the pun) refer to as a “‘misspoken’ string of words” (all puns intended, I’m assuming). Mistakes frame T50YS and riddle it—the narrative, the characters, not to mention the language. At its heart, T50YS confronts all that was wrongly taken. And so there are holes. Many holes. Though beware: those holes, which thread once filled, now lie like scars, injuries, traps. And yet even so, in those lacunae still lingers all that can be suggested, emended, maybe even restored. How the fabric of these lives, our lives, their stories, our stories, might be resewn. The bits reassembled. The dots reconnected. How out of what is destroyed—and allways [sic] will be destroyed—a greater meaning might still be refashioned.

There are several moments in T50YS where something happens before it happens—maybe in pantomime or suggestion, etc.—and actions are told/written as happening before they actually do (i.e., something literally happens only figuratively), and the anticipation of the figurative then turning literal is very scary—anticipation of a fateful manifestation. And when it comes time for the pre-told fatal events in the story to finally transpire, this makes the listener/reader have to go back in their minds (or back to a previous page) and take the words from before and reuse them. Is this what the narrators of T50YS mean when they say the listeners in this story are "made accountable" by the Story Teller?

In order to leap, we first need to practice leaping. Dante leads the reader through a series of levels, literally, where leaps of imagination or association are learned by way of Virgil. Eventually though, Virgil departs and the reader has only Dante. Then Dante departs and the reader must, by way of example and practice, finally take the action every good book should in good conscience prepare the reader for. In the case of Divine Comedy—or at least my paper made this case—Dante leads us to take a leap of faith.

We are all made accountable by the words we receive—how we read them, how we use them, how we change them, how we act on them, or even how we put them aside.

As you already know, everything you’re pointing out in T50YS is there to prepare the reader for the final moment of the book, the final page really. Which as it turns out, as you also already know, is not so final after all. “After all” never is.

Along that same reader-made-accountable thematic thread, what can you say about the complete whiteness of many of the reverse pages in the book? Because they often feel like a screen for the readers to project their own images on while reading. And one could think of Ahab, his crew and The Whiteness of the Whale here. Is this part of the purpose of the beautiful, and sometimes scary, images that appear on some of those reverse pages—a means of encouraging, or even instigating, the reader to mentally fill in the pages that are left blank?

At this point I guess it’s fair to admit that the relation between textual and visual language has always been my bag. Newsflash: Cat’s out of the bag. Newsflash: maybe The Cat was never in the bag? Newsflash: enough of bags but not enough of The Cat.

(Is it permissible to goof off like this in an interview or will Interview Security break down the door? I did notice a sign on the door that sternly states all obtuse references, pompous inflections, not to mention solecistic pronouncements, are seriously frowned upon.)

Which is to say no whale but at the same time also say there is no escaping that whale, Melville’s behemoth, Melville’s page, the double warning nailed to the mast against solipsism in the name of discovery, no matter the reward, or should I say perceived reward?

Which—taking into account all of the white pages in T50YS, and all rectos too—is to also admit to a whiteness just the same, and also not the same, because it’s a whiteness that in T50YS is necessarily personal, where no blade lies—or no blade anyone other than the reader can find—where waits another kind of shearing emptiness, occasionally threaded with a possibility, but never so much or so literal as to deprive the reader of what sharpening insights wait there, to be stitched, or restitched, or even left alone.

For me, what’s slowly — maybe finally — resolving out of all these years of work with fonts and layout, colors and visuals, juxtaposed text, infiltrating text, contrapuntal text, is a deeper understanding of how we think, how we experience information, how we come to the importance of story, how we depend on narratives in the first place to recognize a self even capable of encountering a narrative (I’m starting to believe the creation of the narrative is the creation of the self; and the more expansive that narrative the more compassionate the self). Because in the end we have only this self through which to approach reality—ab aeterno; a reality forever beyond the possibility of fathoming entirely let alone directly—but which in order to live to the fullest of our gifts we must still somehow render comprehensible.

There are certain kinds of literary representations that no matter the subject—whether dragons or manhole covers—will still only activate a limited part of the self. The goal of what I do is not merely to represent or even interpret a subject but provide experientially a process that opens up a way to respond more fully and truly to these living moments we so fortunately inhabit.

As I frequently remind myself (a sort of private shorthand I’ll share now):

Letters are the shadows of our thoughts. Colors, the shadows of the world.

Composition, the oldest voice upon the wide.

It’s not merely what’s said but how what’s said is arranged.

There's a sense of the fear of losing one's self, one's handle on the world, so to speak, to certain fatalistic information—losing autonomy to the factualization of something inevitable, unavoidable. I mean, there's also a whole wealth of interpretation that can go into what you've done with the storyteller in T50YS being named as such, in two words [actually Story Teller], and how the word “teller” also lends itself to monetary/banking connotations as a person who directly handles a debt received or paid out. And all of that also gets tied up with the word "account" and its relationship to "reckoning."

I believe you’re the first person to note the importance of both “Handle” and “Teller.” Who am I to get in the way of that kind of sensitivity, especially when identity and reckoning are at stake?

Okay, what scares you the most?

To find myself enslaved by a lifeless mood which no action, no poem, no reason, no song, no belief, no suffering-love can escape.

Your attention to detail with this book is such that I actually found the copyright page of T50YS to be the most entertaining copyright page I've ever read. Do you ever come up against strong headwinds when it comes to your being involved in so much of the design/book-making process?

I was lucky. Edward Kastenmeier, at Pantheon, bought and championed House of Leaves back in the late ‘90s. Ever since, we’ve been exploring this tricky terrain between images and words.

In what ways did the series of performances of T50YS influence this newly prepared and packaged form of the book?

In what ways did the series of performances of T50YS influence this newly prepared and packaged form of the book?

Hearing the five voices stitching together one story prepared me for the final typography as well as helped inspire the final sewn designs.

So having multiple people involved in the telling of a story is a big part of T50YS—not only thematically, but also in how the actual artwork was made for the book. Is working with other people in various ways something that's going to be important with The Familiar?

It was. Initially, I had these great plans to create an Atelier—Atelier Z—where I could workshop many of the themes, scenes, and visuals; from character to concept; from details to broad outlines. What I had in mind was how architects approach designing complex structures. I loved the idea of something like Renzo Piano’s Building Workshop. Participation would serve as a quasi-school, place of apprenticeship, the kind of gathering I would have wanted to join when I was just starting out in this enterprise of addressing the white page.

Unfortunately, I was pretty naïve. I recently discovered many of those I’ve involved so far have neither the interest nor stamina nor imagination not to mention discipline. I’m actually grateful, though, for their corrective voices. You could say they have redressed my egotism; riven my arrogance. Forced me to re-evaluate my aims and the intentions behind those aims. I don’t really want to teach let alone form some kind of school. As those gifted individuals who do it for a career can attest, handling different temperaments is a full-time job. For me, it just seemed like a way to give back. Offer a leg up. Share a bit of what I’ve learned over the years. Maybe though I’m best sticking with what I know: the novel. And writing a novel is ultimately a solo venture or at least a venture involving a very small but very special fellowship.

I will add here that those who are still part of that special fellowship continue to urge me to keep alive the idea of this Atelier Z. So who knows, maybe something will come of it. It’s just too early to say.

This though is certain: I’m already steeling myself to face again the increased isolation finishing a novel always requires. Especially when that novel concerns a cat.

This though is certain: I’m already steeling myself to face again the increased isolation finishing a novel always requires. Especially when that novel concerns a cat.

Writing The Familiar as a serial novel, and with its twenty-seven volumes being compared to episodes/seasons in a television series, have you been watching many television shows?

The Wire, Battlestar Galactica, Mad Men, Breaking Bad.

What/who are you reading now?

Type: A Visual History of Typefaces and Graphic Styles 1628-1900. Though considering this interview, maybe the time has come to return to Dante.

With The Familiar being slated to be in development for so many years—not to mention the time you’ve already put into the project—are you at all anxious? At all anxious about the changes in life that will inevitably occur during that time, and what the mere passing of all that time will mean to the work? Is that something you’re anticipating as you’re working?

Only Revolutions purposefully stands outside of the times. The language there is born out of the times and yet you will find no such language anywhere except in that book. You might say it is utterly unfamiliar.

Welcoming, however, the intrusions of the times, as The Familiar does, does not guarantee the times won’t overwhelm the quest. Not even an almighty book contract stands in the way when that pale beast comes around. And unlike Interview Security, it doesn’t bang on the door. It just walks through the wall. Any wall. Or bag. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.) And of course if that happens, there’s only one thing left to do . . .

Am I going to have to guess?

Leap.

Nice. Now, your cat t-shirts are becoming quite popular with your fans. Are you wearing a cat shirt today?

MZD:

Have a great Halloween. Near time for midnight to strike.

About the author

A recent transplant from Texas, Matthew Treon lives in Boulder, Colorado where he studies fiction in the MFA Creative Writing program at The University of Colorado. He is a music journalist, a staff writer for The Marquee magazine, the new Assistant Managing Editor for Timber Journal and teaches at the Boulder Writing Studio. His most recent story is forthcoming in SpringGun Press, and he is currently working on a twelve-volume non-fiction project titled Drinking Methanol: The Obscured Tommy Johnson and the First Blues Faustian Bargain.