Photo via Wikipedia Commons

Editors. Who are these enigmatic figures within the literary landscape, skulking on the threshold between writers and readers? Writers regard them with a mix of reverence and resentment. A good editor has the power to lift writing to the next level — but writers hate to think their innate talents need external help. Readers, for the most part, barely think about editors at all, and simply trust them to do their gatekeeping job, keeping bad writing out and letting only good writing flow into the discourse.

An editor exists in the invisible space between literary source and destination, scrutinizing the text, wielding red ink, filtering material, and creating and guiding public tastes. They operate via an unusual mix of humility and power, serving the writer’s needs while also possessing the ultimate authority to say ‘No.’ Even an editor célèbre, like Amy Scholder, currently Editor At Large for City Lights Publishing, stresses her more humble duties first. She feels “most useful” when helping an author find the “most precise way of getting their voice on the page.”

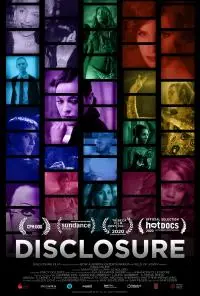

Scholder began her career in publishing in 1985, working part time at the City Lights bookstore in San Francisco. During subsequent stints at Serpent’s Tail, Verso, and the Feminist Press of City University of New York, she’s published work by a veritable roll call of cultural icons, from Pussy Riot to Joni Mitchell, Kathy Acker to Diamanda Galas, William S. Burroughs to Sapphire, David Wojnarowicz to Savannah Knoop. In 2016 she added ‘documentary producer’ to her resume with the multi-award winning Disclosure, and continues to work on film projects, as well as books. She’s clearly done so much more than subtly polish existing writing — she’s been a major influence on transgressive literature in the USA.

Scholder thinks she always wanted to shape culture in some way. She grew up in the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles, knowing she was gay. In the suburbs, in the 1970s, she had no role models. “I had no idea what I was or what my life could look like.” When she graduated from UC Berkeley in 1985, she found a focus and a destination in the City Lights Bookstore.

I felt very drawn to it as a bookstore, as a curated collection of books… it had this function of discovery where I would learn about topics and authors because of the creative ways books were shelved and sections were organized. Beyond that, I liked the vibe... Lawrence Ferlinghetti had his signs all over the store that were engaging in free expression and there was a DIY feel to that environment… So as a young person without any direction, or any idea what the fuck to do with my life or my English Lit degree, I just knew that it'd be awfully nice to spend time in that place.

The City Lights Executive Editor at that time was Nancy J. Peters. Scholder convinced Peters to take her on as an assistant/apprentice, learning “how to edit and publish books — from acquiring, editing, pasting up text, writing press releases, and going to sales conferences.” Rather than doing an internship, Scholder worked evening and weekend shifts in the bookstore to pay her bills. Scholder found this early experience as a bookseller crucial, as it expanded her sense of books as both intellectual property and objects. She learned the value of “adding intentionality in the packaging and presentation and having that correspond with the content.”

Scholder’s first big project for City Lights emerged from her awareness of the crisis rumbling through San Francisco’s gay community. “Half the people I knew were starting to get sick and die.” Concerned that the stigma surrounding AIDS was silencing the other half, Scholder drafted an open call “on my City Lights letterhead” asking for commentary on how the epidemic and the prejudice it generated was “changing artistic practice." She had a keen sense of what might be coming. “Both my parents are from Jewish immigrant families. My father was born in Vienna, and fled Austria in 1939. I grew up understanding that some groups are scapegoated in mainstream society and it's our responsibility to fight that fight.”

She sent her “message in a bottle to everyone I could think of from visual artists like David Wojnarowicz, Duane Michals, Sue Coe, Lynda Barry, Nancy Spero, Leon Golub to literary writers like Edmund White and Lynne Tillman, Gary Indiana, Karen Finley, Kathy Acker, Eileen Myles, and Robert Gluck to more political writers like Abbie Hoffman and Cindy Patton…literally everyone wrote me back.” The resultant City Lights Review, published in 1988, included drawings from Golub and Spero, a photograph from Duane Michals, text from Acker and Wojnarowicz, and a letter from a dying friend to Cookie Mueller, who added a postscript lament. Scholder thinks she “provided a place where people could put their work and created context for that work.” In other words, she asked the right question at exactly the right moment in cultural history. She would go on to collaborate with many of these writers and artists again and again in the coming years.

She sent her “message in a bottle to everyone I could think of from visual artists like David Wojnarowicz, Duane Michals, Sue Coe, Lynda Barry, Nancy Spero, Leon Golub to literary writers like Edmund White and Lynne Tillman, Gary Indiana, Karen Finley, Kathy Acker, Eileen Myles, and Robert Gluck to more political writers like Abbie Hoffman and Cindy Patton…literally everyone wrote me back.” The resultant City Lights Review, published in 1988, included drawings from Golub and Spero, a photograph from Duane Michals, text from Acker and Wojnarowicz, and a letter from a dying friend to Cookie Mueller, who added a postscript lament. Scholder thinks she “provided a place where people could put their work and created context for that work.” In other words, she asked the right question at exactly the right moment in cultural history. She would go on to collaborate with many of these writers and artists again and again in the coming years.

Her next major anthology came together on the East Coast. Mutual friends introduced her to publicist Ira Silverberg, who shared her “aesthetic sensibility around literature.” As the 1990s began, Scholder felt that artists were under tremendous pressure to self-censor. This was the era of Republican Senator Jesse Helms’ legislation to prevent funding for any art deemed likely to turn "the stomach of any normal person" i.e. anything remotely outside boundaries set by white Christian heteronormativity. Scholder believed this cultural tension “really fucked with people’s creative process.” So the question she asked was “If you could publish anything right now, at this time when it’s really hard to do that, what would that work be?”

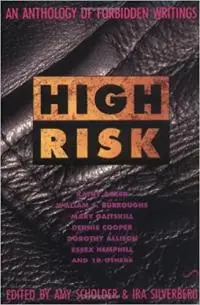

The result was the cutting edge High Risk: An Anthology of Forbidden Writings published by Dutton/Plume in 1991. It featured provocative pieces from Mary Gaitskill, Dorothy Allison, William Burroughs, Kathy Acker, Gary Indiana, John Preston, Wanda Coleman, Essex Hemphill and others. It sold well, was widely reviewed, and its success persuaded Pete Ayrton, the UK publisher, to offer Scholder and Silverberg their own High Risk imprint via Serpent’s Tail. They set up an office in Manhattan in 1995 (“If I really wanted to have a career in publishing, I needed to move to New York”, says Scholder). They published “Sapphire’s first book American Dreams; June Jordan’s Haruko Love Poems; Gary Indiana's Rent Boy; published in paperback Lynne Tillman's Haunted House and Lydia Davis’s Break It Down; and Kate Bornstein’s first novel, Nearly Roadkill.” Scholder says they were drawn to “excellent literary books that were not going to find a home inside the mainstream.”

As the High Risk imprint slowed down in the late 1990s, Scholder broadened her scope from fiction to narrative nonfiction and cultural politics, editing books for Verso, another British publisher with a New York office. She still “gravitated towards storytelling” but was also interested in works that presented other world views, with major authors who were shifting their attention to new subjects, luminaries like Judith Butler’s Precarious Life, Tom Hayden’s Irish On The Inside, and Kate Millett’s mother-daughter memoir, Mother Millett. She reprinted Valerie Solanas's SCUM Manifesto with an essay by Avital Ronell in "a handsome hardcover edition, placing her... into a contemporary context of post modernism and feminism.”

Scholder next became editor-in-chief at Seven Stories, where she presided over a mixed list of fiction and non-fiction. Here, Scholder was able to explore her “obsession with radical women from the 60s” including Cathy Wilkerson, a member of the Weather Underground who famously blew up and escaped from a Greenwich Village townhouse, lived underground for many years until turning herself in and serving time in prison. Her autobiography, Flying Close to the Sun, tells her story of becoming politicized, as do the writings of Ulrike Meinhof, a notorious German underground radical whose selected essays, Everybody Talks About the Weather ...We Don't, was published in 2008. On the fiction side,she published 10,000 Dresses, one of the very first children's books to feature a nonbinary character, and The Others by Seba Al-Herz, a lesbian novel smuggled out of Saudi Arabia.

Later in 2008 she was approached by Gloria Jacobs, the Executive Director of the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, and hired as their executive editor. For Scholder, the challenge lay in defining the purpose of a feminist press in the late 2000s — ”in a publishing landscape where women are published everywhere, but feminists are not necessarily published.” For Scholder, that meant supporting books that reflected an ever-more diverse feminist experience, including Justin Vivian Bond’s childhood memoir, Tango: My Life Backwards And In High Heels and Paul Preciado’s Testo Junkie, alongside forgotten classics like Muriel Rukeyser’s Savage Coast (about her experiences during the Spanish Civil War) and the first uncensored translation of Violette Leduc’s Thérèse et Isabelle. She also compiled an edition of essays by experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer, then in her 70s, and the New York Books Critics Circle Award nominated Hiroshima in the Morning, by Rahna Reiko Rizzuto.

After a change in leadership at the Feminist Press in 2015, Scholder decided it was time to return to Los Angeles. She connected with filmmaker Sam Feder after seeing his documentary about Kate Bornstein. When he told her he was looking for a producer for his next movie, a history of trans characters in film and television, she thought “Well, documentary filmmaking is maybe not a huge leap from independent book publishing” and jumped at the chance.

The outcome was the multi award-winning Disclosure, which premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and sold to Netflix, which streams the film around the world. The sheer scale of its reach and impact was breathtaking to Scholder, used to the vagaries of independent publishing, where selling 4000 copies of a well-reviewed book constitutes success. “It was watched by millions of people, such a different frame.”

The outcome was the multi award-winning Disclosure, which premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and sold to Netflix, which streams the film around the world. The sheer scale of its reach and impact was breathtaking to Scholder, used to the vagaries of independent publishing, where selling 4000 copies of a well-reviewed book constitutes success. “It was watched by millions of people, such a different frame.”

Of late, Scholder has “gone home” to City Lights, where she is editor-at-large. This has given her the opportunity to publish projects such as “Steven Reigns’ beautiful book, A Quilt for David and Pamela Sneed’s Funeral Diva. Interestingly, both books deal with the legacy and the history of the AIDS epidemic. And I have other books in the pipeline.”

After nearly four decades in publishing, Scholder still believes in the importance of writing and writers within culture. “Writing is hard,” she says. “Writing something meaningful takes time… you have to keep at it and write over and over and over again.” The 2021 documentary Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song sums up the tensions of the contemporary creative process for her. “He spent years writing that song and writing hundreds of verses and agonizing over it and as he changed, the verses changed and the meaning of the song changed and all these different layers were discovered over time. Then his record label wouldn't release it. We have to acknowledge that art needs time to develop and that excellence isn’t always recognized or rewarded right away.”

As well as perfecting craft through discipline, Scholder believes writers need to build networks. “Publishing is about relationships with your readers… if you can read in front of a group of people and those people can talk to you about your work, they will be the ones who will want to read it when it's finished. Similarly, if there are presses that you love, and you feel like wow, that publisher keeps putting out books that are finding the audience that you want, then work on understanding the communities involved in putting these cultural products together. Reach out, on social media, by following people, writing notes. Develop relationships with like-minded other writers and publishing professionals.”

Ultimately, now as in 1985, she’s drawn to writing that expresses a “unique voice.” She looks for instances “when somebody understands the specificity of their life and experience or the stories they need and want to tell, and they're able to tell it in a way that I've never heard before, or they create a character I've never met before. And it tells me something not only about something new that's outside of myself, it also speaks to something I need to know about myself.”

These days, for pleasure, she reads biographies and nonfiction. “Part of me is really interested in thinking about how to live a life as an artist or as a cultural producer, what that looks like and what your legacy is.” For someone like Scholder, that can be “a very strange experience,” thanks to all the cultural icons she has known and worked with over the years. “David Wojnarowicz’s and Kathy's [Acker’s] biographies include many stories of our time together. That is really an uncanny experience, reading a book and finding stories about your life printed in these texts. But it is a reminder of the meaningful relationships I've built throughout this career, and the incredible people who are part of my story too."

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .