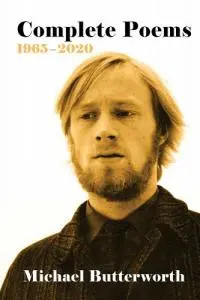

Photo by Sara Jane Inkster

As an essential part of the 60s British New Wave Sci-Fi movement, Michael Butterworth's earliest work helped define this "new writing" in the groundbreaking New Worlds Magazine, taken over in 1964 by Michael Moorcock to foster this pivotal sea change. After many of these short pieces would be compiled in his collection Butterworth, he'd author his first novel, My Servant The Wind, before writing the Hawklords series of fantasy paperbacks based on the rock group Hawkwind. Butterworth would eventually start Savoy Books, a bookshop and publishing house in Manchester where he'd release the controversial Lord Horror novel by David Britton, which he also contributed text to and edited. The book triggered one of the longest, most truly fascist examples of "cancellation" our society might ever see, and makes our current state of knee-jerk culture look crybaby in comparison.

But far beyond his experimental, prescient glimpses into future and revolutionary tales of the past, Butterworth is a poet at heart. This week Space Cowboy Books releases his Complete Poems 1965-2020, which chronicles his dynamic life through verse. A book with an accompanying album of guest musicians backing up his reading of selected pieces, Complete Poems is a hybrid document of an exceptional man's journey, one Alan Moore (The Watchmen, From Hell) calls "rolling news from a since-outlawed territory of ideas; bulletins filed from a redacted country, edited out of cultural continuity... human moments are examined as though artifacts dug from the future, or the debris of a missing world. Caught in a jeweler’s eyepiece, fugitive impressions from near sixty years of subterranean endeavor here condense to lyric crystal, ringing with the poet’s radical and laser-guided voice."

This new poetry volume is much more than just a collection—it’s an artful memoir of sorts, going beyond the mere chronicles of a pioneering New Wave science fiction author and into the near full arc of a human being, from innocence to angst to peace. What prompted this project?

Thank you, I’m pleased you see it this way, but the intention came at the end, after I had collected the poems together and it was pointed out to me that they told a larger story. When I wrote the poems, the quintessential romantic in me, far from being artful in intention, struggled to find direction, often resigning himself to the belief there was none, and harboring the doomful despair you can see in some of the poems. But after the fact, I can see it, because individually each poem is a record of the moment in which it was written — when an event occurred, or a thought struck — and a lot of the poems are also confessional. Once I could see myself, my own life, as a unifying element, I knew how to shape the book. Suddenly being able to see how it all fitted together, very late in my life, realizing that it hadn’t all been in vain, that there was a pattern after all, came to me as a kind of final revelation.

You include a cliff note overview of your life in the intro, which may assist the uninitiated to put these poems into context, but what does poetry offer you that you can’t otherwise express unabridged in regular narrative?

Whether to write in verse or prose is something that is dictated inside me, and I’m not sure what the reason is. Perhaps it is a feeling, of wanting to be either tightly controlled or expansive, that decides me. Writing poetry is a way of condensing meaning — feeling, thought or action — in a manner that retains coherence. A rhymical arrangement is important. Perhaps it is the satisfaction that is to be obtained from doing that. Or perhaps different internal voices come into play, different literary voices, and sometimes it is one and sometimes another.

Whether to write in verse or prose is something that is dictated inside me, and I’m not sure what the reason is. Perhaps it is a feeling, of wanting to be either tightly controlled or expansive, that decides me. Writing poetry is a way of condensing meaning — feeling, thought or action — in a manner that retains coherence. A rhymical arrangement is important. Perhaps it is the satisfaction that is to be obtained from doing that. Or perhaps different internal voices come into play, different literary voices, and sometimes it is one and sometimes another.

I wondered about including the preface, the overview. My publisher, Jean-Paul, said he liked it, and so I retained it, but he was right. It provides context, as you say, and perhaps more importantly it acts as a distinct work in itself, a self-contained memoir written now, by an older man looking backwards, to which the poems themselves, written then, have become a kind of unifying coda… which is how I sometimes read it.

What did it feel like in the mid-60s when you were being “feted as a young blood of the new wave of Science Fiction?” Did it feel like a tangible movement you were part of, an out with the old in with the new? Has history distorted our perception of that time in literature, or has it yet to receive the proper credit it deserves?

‘Young blood of the new wave’ may have been something Judith Merril came up with. She wrote something similar about me in England Swings SF, her heady collection of the new fiction. I have sometimes used the phrase in bios about myself because it does very definitely describe how I felt, and maybe how others felt too. The new wave, for me, happened with a bang, when a year after leaving school in 1963, aged sixteen, I found my work being seriously considered for publication. After a few letters of rejection, I sold my first story, ‘Girl’, about a sexual encounter between the last two men, to New Worlds in May 1966, not long after Michael Moorcock had taken over as editor. I had then just turned nineteen. It was the kind of writing that no one else at that time was publishing, certainly not in the conservative and largely moribund SF field at that time, but also not in the period’s literary journals, which New Worlds, an outlier in the SF field, under Mike’s guidance, would soon come to have more affinity with. It wasn’t only the subject matter that deterred other editors. The style of writing did too. It didn’t conform to the accepted norms. This first sale led on to others, mainly to New Worlds but also to anthologies round the world as different countries weighed-in on the new movement.

What this felt like to a young writer just starting out, was phenomenal. The crusading ideological editorials and articles published in the magazine, and the cohesion Mike and J.G. Ballard gave the new wave, as it had become known, made it feel like a movement straight away, a big part of which was, as you say, kicking out the old and replacing it with the new. New Worlds reflected this. But Mike had taken over an existing SF journal, with an existing readership, and to avoid losing readership he had to be careful about the rate at which he introduced this explosive ‘new writing’. The early paperback editions were, accordingly, a patchwork of the old and the new, but very gradually the ‘new’ superseded the old, and by July 1967, when New Worlds received an Arts Council grant and the magazine became large format, the process was completed. The large format editions presented the opportunity to extend the new wave into the visual, and in terms of design, contemporary visual art and typography, they became a presence to be reckoned with on the newsstands. In this form, the magazine lasted from 1967 until 1970, and those years correspond to the apex of the new wave in the UK, the time when I felt most ‘feted’, as Judith put it, receiving the kind of acclaim one expects to get at the end of their career, which for me happened at the beginning, and in hindsight this was not all a good thing, because what it then began to feel like, after April 1970 when the newsstand editions of New Worlds collapsed and the new wave was over, was anything but enervating. New Worlds was ahead of its time, and far from being hailed and copied by other literary journals, it was seen, if it was seen at all, as being a harbinger of what not to be, a tragedy for me, because I not only lost my market, I also couldn’t find one elsewhere.

I don’t feel the period has been ‘distorted’; the fiction has received fair assessment in Colin Greenland’s The Entropy Exhibition, and David Brittan has covered the new wave’s equally important visual side, see his Eduardo Paolozzi at New Worlds, and beyond these books, various academics such as Christopher Dayley (British Science Fiction and the Cold War) and Tom Dillon (What is the Exact Nature of the Catastrophe?, about the movement’s cultural history) have given excellent assessments. But I do feel that New Worlds has been ignored by the literary field. Quite apart from the ‘new writing’ it produced, all of which was astonishingly innovative for the time, it was receptive to acknowledged literary authors, becoming, for instance, D.M. Thomas’ home for a while. A great deal of Thomas’ speculative poetry appeared in New Worlds. Why was the journal never sufficiently acknowledged outside of SF? I believe, this is due to English snobbism, because of the ‘taint’ of science fiction. Had the journal been published in the States it might have been embraced by the literary field and might have survived as a literary innovator.

You mention losing your voice as writer in the 70s, which led to the urge to become a publisher when you founded Savoy Books. “In literature, unlike art, you’re either one thing or the other,” you say—is this to suggest one can’t write and be a publisher? Do you see it as a conflict of interest, or focus perhaps?

That contention, that “…in literature, unlike art, you’re either one thing or the other, a writer or a publisher” was said after having had a masters paper written about me by an American fashion artist, Hannah Nussbaum, who noticed how my work repeatedly segued from writing into publishing and back again. Her tutors were Jeremy Millar and Brian Dillon, at the Royal College of Art, and it astonished me that artists rather than writers were taking the trouble to write about me in this way. No one had bothered critiquing me before, and it made me question why no one in my own field was taking this trouble. It was due to other artists, a British collective known as The Exhibition Centre for the Life and Use of Books that the first exhibition of my publishing and writing work (called Butterworth) was held, at the Anthony Burgess Foundation, Manchester, in 2014, and then toured to the Special Collections Library at Kent State University as The Green Frog Exhibition. So yes, I think I am saying it isn’t possible to be both, at least in the eyes of the writing world. You can be… but as I have found out you risk not being seen. This blind spot might be something to do with focus, in the sense that the main creative focus is on the writer rather than the publisher. The latter is seen as being non-creative. I had changed practices to that of a publisher, and it was simply assumed that with the demise of New Worlds I had stopped serious writing.

Publishing is part and parcel of my writing, and the urge first came to me when Jim Ballard took me under his wing briefly in the late sixties. One of the things he did was to show me how to ‘sub’ my work in the manner of William Burroughs, but he also told me I needed to be more prolific if I wanted to make a career of writing, and to invent my own mythology rather than to rely on Burroughs’.

My solution to the lack of prolificity was to become a publisher. In this way I could work with the texts of others as well as my own. My first publication was a literary broadsheet called Concentrate, the name inspired by the process which Jim had shown me, and which at the time he was practicing himself. His ‘condensed novels’ were appearing in New Worlds, Ambit and other magazines, and were eventually collected as The Atrocity Exhibition. Jim’s ‘lesson’ involved him condensing two pieces of my writing, and the result saw publication in New Worlds as ‘Concentrate 1’ and ‘Concentrate 2’. For my first publication, I simply took the title from them. It was a development of the same idea. A glossy 4pp foolscap broadsheet, Concentrate ran for one issue and was filled with short and condensed writing and poems, including by New Worlds writers John Sladek, John H Clark, Charles Platt, James Sallis, Bob Franklyn and myself (as by Edward Poe) as well as the poets Anselm Hollo, Alexis Lykiard and others. It was distributed free inside New Worlds #185 in December 1968, and in Ambit around the same time.

Following this came Corridor, which was more magazine-like, which ran for five editions, before I changed its name to Wordworks, and in this form it ran for a further two issues. Many years later, in 2010, I relaunched Corridor as Corridor8, incorporating contemporary visual art in the mix. Whilst I was doing the earlier iteration of Corridor I came across David Britton, and after the last Wordworks appeared we started Savoy Books in 1975. Publishing became increasingly important for me as a writer, and my early period produced some of my most important pieces of fiction, such as ‘Das Neue Leben’, but finding a publisher was still difficult. Written during the eighties this piece didn’t see publication until twenty years or more later, in 2011. Another new piece of work, ‘A Hurricane in a Nightjar’, I had to publish myself. It appeared in one of our anthologies, Savoy Dreams, in 1984. Both pieces would have been impossible to write out of my publishing context, and ‘Das Neue Leben’ was the main precursor text to Lord Horror, David Britton’s novel, published in 1989. Writing that, we used our own texts and others. One piece of work would inspire another. I thought after Lord Horror, at least, it would be seen what I was doing.

You co-authored, edited, and published the controversial novel, Lord Horror, which Cold Tonnage Book Catalog considered an “offensive against the establishment” and Ramsey Campbell called “a truly dangerous book.” For a work whose sole intent was anti-fascist, to be not only censored but destroyed by actual fascist techniques when the raids occurred at Savoy Books—I can’t imagine how terrifying that must have been for you, but was there any feeling of resolve, that you and David Britton’s sole point had been proved in real time? What makes mere words “dangerous?”

There was a feeling of resolve, yes, and as we found ourselves feeding real events into our fiction there was a certain glee in it. But there was little satisfaction. For twenty-five years we were at the butt end of police efforts — under Police Chief James Anderton, a Don Quixote type who fought at windmills — to shut us down, and as literary ideologues we had to defend ourselves. We fought back in the only way we knew how, and Lord Horror and other publications became grist for this windmill, as he imagined us. He won most of the battles. These were awful to go through at the time, but he didn’t win the war. Words did. Words are dangerous only if someone perceives them to be, and Mr Anderton, a man of the Bible and the past, did do. But the forces he found himself up against in contemporary society, which I ranged against him as best as I could, were ultimately undefeatable. Lord Horror was a way of lampooning James Anderton, and fascism more widely.

Our novel is, in Hannah Nussbaum’s phrase, a “word crime”. It is extremely dark, showing what happens to individuals when they are part of something that is seen as disposable. The treatment of Jews and others in the death camps was even more horrific for this reason. Designated as walking dead, then treating them as ‘scientific’ research? These were taken to absurdist extremes in the book. I wrote Lord Horror because I saw the concentration camps as ‘practice grounds’ for the way in which the world was going as it ran out of resources, and if nothing was done in time to arrest the process. Some of the worst suffering in the ‘camps’ was when the Nazis were losing the war and basic supplies began drying up, and real starvation and neglect set in. This will happen to Earth, too, I speculated, if we don’t or can’t change course. David wrote the book for different reasons, but I saw the novel as a way of getting these ideas out. In Reverbstorm, an abortive filmscript-treatment sequel, we envisaged together the killing-city of Torenbürgen. The film didn’t materialize, but Dave and John Coulthart developed it further and turned it into a graphic novel.

The poem “Until Now” (from the 1968-1975 section of the book) is one of the most convincing analogies of viewing the earth as a female being violated. Do you see any hope for our descent into ecological disaster or have we slid past the point of no return?

Thank you. We are already past that point, yes. The devastating fires, extreme weather, rising sea levels, mud slides, vanishing ice, famine, flooding, homelessness, increasing outbreaks of virus infections like AIDS and SARS and the loss of species. It’s too much of a coincidence to think this variety and frequency of things is due to normal changes in the weather. Nothing on this scale has happened in my life before. A positive human response, a change of course, is crucial, yet we are being held up by wild beliefs that have taken hold, an impending world war and a reluctance by many to accept we can’t just have business as usual. If we started to view the mantle of life on Earth as an interconnected entity, as a human being in fact, and understand that every action has consequences, there is still time to limit what is happening, a difference can be made. Vast in numbers as we are, our behavior can be changed. We don’t even have to turn against our economic systems, because even, say, capitalism can change, and there are signs that it is doing, that it is becoming more ‘steady state’ rather than big bang. It needs to flip, away from the mantra of growth, and see that individuals in our wealthy nations are prepared to make sacrifices that are needed for the sake of survival and to help those regions of the world that are at the front line. But will it happen in time? That is the real knife-edge.

Thank you. We are already past that point, yes. The devastating fires, extreme weather, rising sea levels, mud slides, vanishing ice, famine, flooding, homelessness, increasing outbreaks of virus infections like AIDS and SARS and the loss of species. It’s too much of a coincidence to think this variety and frequency of things is due to normal changes in the weather. Nothing on this scale has happened in my life before. A positive human response, a change of course, is crucial, yet we are being held up by wild beliefs that have taken hold, an impending world war and a reluctance by many to accept we can’t just have business as usual. If we started to view the mantle of life on Earth as an interconnected entity, as a human being in fact, and understand that every action has consequences, there is still time to limit what is happening, a difference can be made. Vast in numbers as we are, our behavior can be changed. We don’t even have to turn against our economic systems, because even, say, capitalism can change, and there are signs that it is doing, that it is becoming more ‘steady state’ rather than big bang. It needs to flip, away from the mantra of growth, and see that individuals in our wealthy nations are prepared to make sacrifices that are needed for the sake of survival and to help those regions of the world that are at the front line. But will it happen in time? That is the real knife-edge.

These poems run the gamut from love to historical to speculative and even hard science like the piece “The Chemical Genesis of The Known Universe,” where organic compounds like cyclohexylamine, furfuryl, butyrolacetone are given a sentient purpose, as if part of the divine plan of creation. My question has no foundation in science, maybe more intuitive, but do you think there’s any chance humankind could eventually adapt to the more caustic chemicals that are destroying the earth as we know it? While its horrific they are now finding plastic bits in newborn babies, could our flesh one day fuse positively with foreign matter? Is humankind as we know it just a mere phase?

I have in the past, metaphorically, and in despair at our behavior, darkly viewed the mantle of life on our planet as humanity’s placenta on an evolutionary journey, to be discarded as we make our escape. If our forests and oceans are seen as being disposable, then there’s no need to take care of them, or respect the lives of the lower creatures who have supported it, our cousins and ancestors who still regard them as home. But we can’t even agree amongst ourselves to get off the planet! One of the poems in the book, ‘Premature’, in the ‘1968-1975’ section, written in the early seventies before it became impossible to see Earth as other than a limitless resource, is about the end to the ‘space race’, selling-off of the hardware and the mothballing of plans to build human habitats in space. Well, I bet there are some wealthy people now who wish we hadn’t stopped when we did, and that we had colonies in space they could jump to before everything collapses. It was those same wealth-seeking short-termism people that stopped the race in the first place, and they must be worried now that they did. It’s the only convergence of views I share with them. I thought at the time stopping manned exploration was a colossal error, and it makes me feel that Homo Sapiens might be just a phase, too tied to the tribal coding that first made this particular hominid successful, but which is now revealing its limitations. The problem is, there are no other new hominids coming out of Africa these days. We might be the end of the line.

Music has played a large part in your life—from the 60s counterculture to authoring the Hawkwind fantasy novels, to Savoy Books creating the Savoy Record label, which helped prompt The Blue Monday Diaries when you spent studio time with New Order. Your new poetry collection also comes with a musical spoken word album—did you feel an essential urge to put your voice to these pieces?

No, this was the idea of my publisher, Jean-Paul, at Space Cowboy Books. He runs Simultaneous Times, a podcast of him and others reading the works of new writers and poets. He had done a couple of readings from my collection Butterworth, and just as Complete Poems was about to go to press, he suddenly asked whether I would read a selection of poems from the book, not just for ST but for an album. I had hardly ever performed my work, but I found myself with a microphone and a list of poems to read. A quick lesson in Garageband got me started, and over last summer we made the album together. The poems are set to music, there are twenty-four tracks, and it is my first album.

The books ends peacefully, at times even playful. Do you see the 2001-2020 section as a reflection of your more recent Buddhist practice?

Yes, I do. The concluding section, ‘2001-2020’, was initially called 'Emptiness and Death', and many of the poems included in it are the results of me facing what happens when the causes and conditions that have produced me, cease — as they will soon do. The section also reflects an attempt to move on from darkness, to turn away from writing ‘warning’ fiction and poetry, which is difficult for me to do because ‘warning’ is what I do, and I can do it well. How to write poetry that is warm, playful and inclusive yet is not blind to what is happening, then?

Get Complete Poems 1965-2020 via Space Cowboy Books at Bookshop

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.