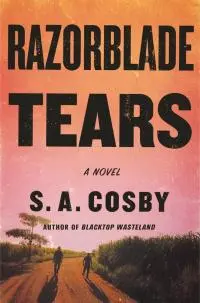

On the still-smoking heels of his breakout novel, Blacktop Wasteland (Flatiron Books, 2020), current Southern Gothic-Noir potentate S.A. Cosby delivers the highly anticipated follow-up, Razorblade Tears, today on July 6th 2021. An even more challenging story than its feral hot-rod predecessor, Razorblade Tears follows Ike and Buddy Lee, the conflicted tag-team of grieving fathers who cover a blazing swathe of Red Hill, VA to avenge the deaths of their two gay sons. It's a delicate tightrope walk of dynamite wick burning at both ends, taking crime-fiction into uncharted territory where one must possess a thick skin to preserve the sensitivity of their heart, and I can already tell Cosby has another blockbuster on his hands.

Razorblade Tears takes place in the same Red Hill, VA township as your breakout novel, Blacktop Wasteland, yet I feel they are two extremely different approaches to Southern crime fiction. To me, Blacktop Wasteland is a much more atmospheric noir with focus on landscape, deeper character development, and the adrenaline of souped-up car fetishism to propel an update on the classic "one last job and I'm out" heist story; whereas Razorblade Tears is much more socio-politcally topical with a clear agenda to educate through a tale of regret/revenge. Beyond merely showing your range, what was the motivation to tell such a different story?

For me it was as much about challenging myself as it was challenging my readers. I believe writers get stagnant the moment they don't try to push themselves. You may succeed or you may fall short of your goals, but you're still moving forward, and by doing so you get better. And we all want to get better.

Blacktop Wasteland seems to be getting a whole new wave of love right now, a year after its release — its influence still spreading, gearing up for a seamless transition as we anticipate Razorblade Tears. BW was released right in the middle of what I feel was the most condensed, intense time of 2020's social upheavals — do you think the timing helped or hindered it?

I think the timing was serendipitous because sadly, the issues I'm talking about in Blacktop Wasteland are omnipresent. Tragic and toxic masculinity, poverty, racism, complex family dynamics — these issues are always with us. 2020 just brought them into crystalline focus

Blacktop Wasteland got optioned for film last year and is currently being adapted by Virgil Williams. Were you thinking in more cinematic terms when you were writing Razorblade Tears in tandem with these developments? I ask because RT is clearly higher drama, wider scope, more heart-string tugging, altogether more morally-conscious than the high-speed transcendent nihilism of BW.

Blacktop Wasteland got optioned for film last year and is currently being adapted by Virgil Williams. Were you thinking in more cinematic terms when you were writing Razorblade Tears in tandem with these developments? I ask because RT is clearly higher drama, wider scope, more heart-string tugging, altogether more morally-conscious than the high-speed transcendent nihilism of BW.

Well, even before there were any movie deals I was writing in a cinematic style. I'm a huge movie fan and I tend to "see" my story cinematically in my head. It's just a part of my personal style. That style married with the subject matter made for an exciting writing experience, and hopefully that excitement will translate to the readers

Razorblade Tears hinges on the eye-for-an-eye concept, propelled by very timely elements of homophobia/transphobia as two fathers, Ike and Buddy Lee, avenge their son's deaths while trying to be better people themselves. Yet, they seem relentless, unrepentant every time they waste a motherfucker — un-phased every time they punch someone's card. The body count is high in their campaign for vengeance, even some innocent collateral death. Of course, this is fiction — a morality tale to show extreme consequence for people's actions, vigilante-style. But in real life, do you see any righteous reason to kill?

I think there are situations where any person with an ounce of empathy or sympathy would feel justified in taking mortal revenge. But, this is the big thing — the effects of that decision can be worse than the motivation for that revenge. I personally believe most people are not wired to take another person's life. That's why those who can do so without any emotional consequences are rightly labeled dangerous. So while we may feel morally justified if, say, someone kills our parents, to avenge them in the end — we have to rise above that desire for the betterment of our own souls. Ike and Buddy Lee are dangerous men, so they have given into that desire to the detriment of their own psyche. And they know it.

In my column here last month "The Obsolescence of the Hero's Journey," I cite the very last passage of Blacktop Wasteland as an abrupt yet sincere example of true human behavior — how sometimes we just can't change, and that's the end of it. Since the book ends so morally dangling, did you know at the time you wrote it that that was going to be the last line? For what it's worth, it remains my favorite last line because of its sheer audacity — for me it's very relatable, resonant.

I struggled with the ending of Blacktop Wasteland because I wanted to show change is not guaranteed despite all the compelling reasons life may throw at us. So I wanted there to be a lot of ambiguity about what Bug ultimately decides to do. The line itself is the most honest moment for Bug in the entire book, and for me that was the right place to end his story.

You've frequently mentioned growing up poor, how it makes you appreciate all the good fortune that's come your way over the last couple years. For me, one of the best parts of being an S.A. Cosby fan has been witnessing your very organic, well-deserved rise — it shows this kind of ascension can still be based on raw talent rather than being born privileged or well-connected. Did this all take some getting used to, the proverbial spotlight? Does it come with its own sets of problems as a writer, whose craft relies on solitude? What advice would you give to someone who might one day find themselves in a similar transition?

It's funny. I'm a pretty extroverted person, so when BW started to gain some traction I didn't really feel overwhelmed. Anyone who has ever met me knows I love to talk and I especially love to talk about writing. But as the book has begun to take on a life of its own I have felt pulled in several directions at once. There are times I have to say no to something and I feel that some people think I'm being arrogant or "gone Hollywood." Nothing could be further from the truth, but I am aware I can't control that sentiment. I'm still country right down to my boots.

But I'd be lying if I said it doesn't feel amazing that people seem to be connecting with my work. And whatever pitfalls my increased visibility may cause, they are more than outweighed by the sheer exhilaration of seeing my name on the cover of a book.

As far as advice: Keep your feet on the ground and your nose to the grind stone. Whether you're an aspiring writer or an established author, nothing happens without the story and the story can only be written if you are actually doing the writing. In the end that's all that matters

Get Razorblade Tears at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.