I slept on Nintendo sheets. Lots of nights when I was young, when I was lucky and the one set of Nintendo sheets ended up on my bed instead of one of my brothers' beds, I would lay down, and Mario and Link would protect me from all those childhood monsters. The decision as to whether the pillow case would be Zelda-side-up or Mario-side-up was a serious one. Even though it was dark, even though I couldn't see them, even though I was a little too old to have sheets with characters on them, I loved those sheets.

I loved those sheets. I loved being surrounded by video games.

Some stuff has changed. I'm the proud owner of a bed too large for those Nintendo sheets, for example. And my love of video games, though strong, has grown up a little. I still love games, but I also love thinking about games in new and different ways. Which is why I was so excited when I first stumbled onto Boss Fight Books.

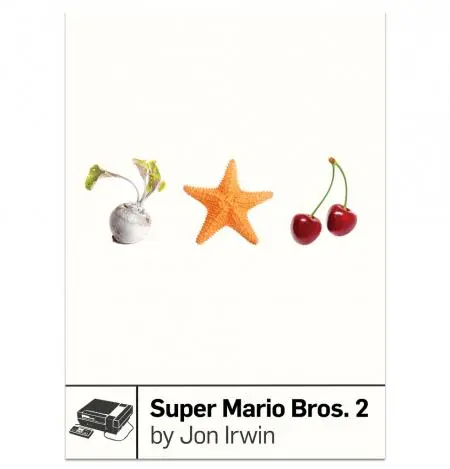

Boss Fight Books is a series Kickstarted by Gabe Durham. Each book stands on its own and focuses on a single game. Releases so far include Earthbound by Ken Baumann, Chrono Trigger by Michael P. Williams, ZZT by Anna Anthropy, Super Mario Bros. 2 by Jon Irwin, Jagged Alliance 2 by Darius Kazemi, and Galaga by Michael Kimball. A second series is in the works and set to release soon. Books in the second series include Metal Gear Solid by Ashly and Anthony Burch and Spelunky by Derek Yu.

When I first saw the series online, I thought it might be worth a look. I thought this might be a great way to let my new, big-boy-bed-adult self enjoy video games. I thought maybe I'd dig these books. Then I saw they put out a Galaga book by Michael Kimball, an author the world needs to hurry up and discover, hurry up and devour. From that point, I was in.

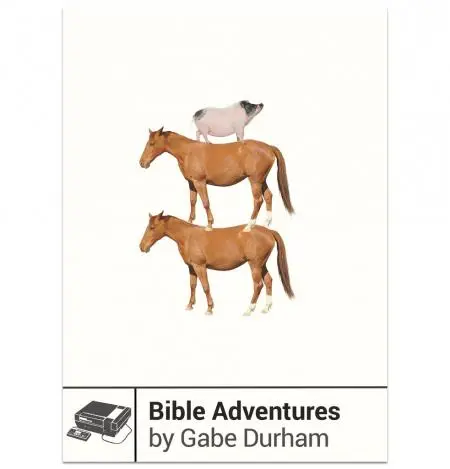

I got the chance to talk to Gabe Durham, series editor of Boss Fight Books and new author of Bible Adventures, one of the books coming up in season 2. Durham had a lot to say about books, video games, editing, print, and even what makes something artistic. It's a fascinating chat, and there's a lot here for gamers, readers, and writers. And, you know. Humans.

I'll ask a single favor of readers before we get started:

Please forgive me when I make an embarrassing fanboy of myself. Because I am an embarrassing fanboy.

Mr. Durham and I spoke by phone.

I've read most of the Boss Fight Books, and they're about video games, but they’re also about a lot of other stuff. When I'm first telling people about the series, I struggle with how to explain, exactly. How do you go about your elevator pitch for Boss Fight Books?

[laughs] I was mostly going to listen to what you said.

I try out "the 33 1/3 of video games" on people. That works when people know 33 1/3. Which I think a lot of readers and hard core music fans do. But it's fairly niche. So if people haven't heard of that, I say, "Well, we're doing a series of books about video games where each book covers an individual game." And that's where they ask, "Are they novels or strategy guides?" I'll say, "Not really," and explain they're more historical, more like a critical take, similar to how a movie critic might write about a movie. The author might tell his or her own story or a story about the people who made the game.

I'll rattle off some of the possibilities, and then either their eyes glaze over or not.

And then you can tell if you've hooked them or if they're off somewhere else.

Totally. You know, there's never the perfect way to explain it. I want to nicely pitch the series in a way that sounds good, but I have less control when people discover the books online. People will find one book or another first, which colors their opinion on what they see the series doing. Somebody who reads Jagged Alliance 2 first is going to have a really different impression than somebody who reads Earthbound.

You mentioned 33 1/3 and that being an inspiration or a touch point. That series is made up of these small books that are often about a single album. Can you talk about the appeal of books that tackle a small subject?

There's a lot of potential when you focus on something small. A lot of the writers I like employ that trick. I'm a big fan of Nicholson Baker, who will often narrow a book down to being about a single afternoon. He'll spend time spinning an object around in his mind for a while and kind of see what revelations come up from there.

I think the focus implies a certain patience that isn't always in step with our times, which can be really enjoyable. It also allows us to geek out about a certain thing that we might not always have the chance to geek out about.

A lot of the books I found that existed about games, for a long time those were more like histories of video games as narrated by the winners. That's got its place, but it's only one part of the picture, and I'm not quite as interested in commerce as I am in games and people and what games do to people, how we interact with these new technologies that have only been around for a number of decades.

To get back to the question, the other thing about focusing in on a small object, something small can be a prism through which you see the world. You begin in this confined space, but it affords these unique opportunities to get into any number of other topics. Anna Anthropy's ZZT is a good example of how a game allows us to explore the early days of online communities. She explains why the game ZZT was important to her, but then she explains how ZZT allowed her to find other people and how other people found each other, how these communities sprang up and what they were like. You need that starting place to explore this thing, but where you wind up is much larger than simply looking closely at a little text-based video game.

To get back to the question, the other thing about focusing in on a small object, something small can be a prism through which you see the world. You begin in this confined space, but it affords these unique opportunities to get into any number of other topics. Anna Anthropy's ZZT is a good example of how a game allows us to explore the early days of online communities. She explains why the game ZZT was important to her, but then she explains how ZZT allowed her to find other people and how other people found each other, how these communities sprang up and what they were like. You need that starting place to explore this thing, but where you wind up is much larger than simply looking closely at a little text-based video game.

That felt especially true in the ZZT book. It starts so small. ZZT wasn't a huge game the way we think about huge games today, and the book goes to a really unexpected place about identity. All of a sudden I was finding out these very personal things and seeing how people were expressing personal things through games and gaming, and that was just fascinating.

Sometimes I work with authors on the structure of the book, but ZZT came fully-formed from Anna Anthropy, even in the first draft. I thought of it as these beautiful concentric circles. You start with just her and the game, and then she discovers how to make games with the game, and that opens up her world further. Then she discovers the other people, then the larger internet, and it just keeps getting bigger and bigger.

You're the series editor, and you work with really different authors who tackle really different subjects. And these authors, they're writing some really personal stuff. They care a lot about their subjects. I know it can be tough to edit, to be that critical voice when your writer is really invested in the subject. How do you go about editing the series?

It winds up being a really different process for each book, which is something I really wanted, particularly when I was scouting for that first group of authors. I wanted books that would do different things. When I talked to the authors, I had that idea of doing different things in my head, and I was excited to see it come together. For instance, when I first started talking to Darius [Kazemi], he had a number of games that he thought he might be able to write about. But when he started talking about Jagged Alliance 2, he told me he could interview all the developers and talk about the development history. The kind of larger, puzzle part of my brain thought, “Oh, we don't have one of those yet. That would be fantastic!”

In terms of style, where each author is coming from, they're very different. My philosophy is about being very involved. I give a lot of notes, but I try to do so in such a way where I help the author follow their own vision. Part of my job is to figure out what they're trying to do, what's succeeding, and how can we make it more like that thing. How we can push even further toward that goal.

Basically, find what's really great, highlight that and see how you can help bring it to the forefront?

Yeah. Writing about individual games is such a wild experiment, so I end up asking, "Okay, why does this book exist?” Sometimes that's an easy answer and it's right there from the beginning, and sometimes you have to search for it. What are we exploring? What was the initial pull of this game? Why does this deserve to be read? Each game calls for a different telling, and each author brings such a different personal history, skill set, and style to the table. The difference between the books becomes really natural.

One of the books I'm working on now is Metal Gear Solid with Ashly and Anthony Burch. What's really fun about it is how they're employing such a casual prose style that we haven't gotten to do yet. There's a ton of jokes and this kind of sibling banter. They go at each other a little. I've seen their whole web series and played Borderlands 2 [both were involved in the creation of that game], and I feel like I have a good sense of that style. It's a real pleasure to see that laid out in book form. So we're pushing towards that and trying to make that as good as possible.

I started reading Earthbound, and that's the only one I stopped reading because the author was explaining the game, and it sounded like my kind of bonkers. I wanted to play first and experience those surprises. But Ken Baumann, who wrote Earthbound, is also the designer of the books and the covers.

Right

These are gorgeous books. The covers look amazing, and they feel really good. I feel like people miss out a little when they don't get the print. Can you tell me about the importance of print in the series or to you personally?

Ken was part of the process pretty much from the beginning. I had this idea, I was talking to friends about it, and he was the first person who really got it. He got really excited about it, and we started talking about possibilities. Later that day he texted me and said "I've been thinking about the press, man. You've gotta do it. Such a cool idea." I told him I'd do it if he wrote a book for me. We became partners in crime from that point on, and he was instrumental in helping me design the aesthetic.

There was this series of reprinted Foucault books that he liked a lot, and he did a similar thing with our books. A photograph of a real world object that points to something in the book, and in this case something in the game itself. That wound up working really nicely. I think the minimalism of that style allows us to be playful. We think about what might allude to something in the game, which is how you get the solutions like the hedgehog who looks like Lavos from the end of the game Chrono Trigger, or the Super Mario Bros. 2 combination of cherry starfish and turnip that look like the slot machine between levels in that game. We get to be playful, but we also denote a seriousness and say, "We're serious about these books." This isn't just a walkthrough of the game or fan gushing. We're trying to do something.

There was this series of reprinted Foucault books that he liked a lot, and he did a similar thing with our books. A photograph of a real world object that points to something in the book, and in this case something in the game itself. That wound up working really nicely. I think the minimalism of that style allows us to be playful. We think about what might allude to something in the game, which is how you get the solutions like the hedgehog who looks like Lavos from the end of the game Chrono Trigger, or the Super Mario Bros. 2 combination of cherry starfish and turnip that look like the slot machine between levels in that game. We get to be playful, but we also denote a seriousness and say, "We're serious about these books." This isn't just a walkthrough of the game or fan gushing. We're trying to do something.

The covers look attractive on their own, and if you're a player of that game you'll see the wink and the nod in there. And you know, sometimes you'll be reading a book on the bus or whatever, and the cover is a little embarrassing. These are books I never feel embarrassed to carry around.

That's good to hear.

There's also a certain prestige to printing paperback books. This enterprise is valuable enough to be printed. We sell more eBooks than we sell paperback and that's great, but I love print books. When I read a book, it's usually a print book. Something about that tactile experience is important to me, and I know there are a lot of other people who feel that way.

Let's talk a little bit about crowdfunding. You've run two super-successful Kickstarter campaigns. The first one was 900% funded, and the new one is over 1000%. And when I say successful, I also mean that after the first campaign got funded, you delivered. What were some of the things you did really right, and were there some things you'd do differently when it comes to crowdfunding? And are there any ways you would advise someone who is considering crowdfunding a project?

I did a lot of research into Kickstarter during the first campaign. One of the things that I took to heart, you need to show people you're really serious about what you're going to do. A lot of people have been burned by Kickstarter. There might have been a golden age when people gave without worrying about whether a project would happen, but those days are over. We're all a little warier about it, with good reason.

It was really important to have the covers finished. We showed that we've got the authors, we've got covers. We showed that we're already at work on these books. We wrote some copy about what the books were going to be like. To me, those might be the biggest reasons we were successful. Bring people an idea that isn't being done yet (at least not in English. There is an Italian series we recently found out about), communicate it seriously, and show that you're serious about putting it out and making it good.

The second time around it was about getting people excited for the continuation of the project. I looked really closely at Nintendo Force Magazine and their Kickstarters. They did a nice job of checking in and saying “It seems like a lot of people like what we're doing. If you like it, we'd love for you to renew your subscription.”

During the second Kickstarter it was hard to predict what would get people the most excited, but what connected most with people was the promise of the Spelunky book by Derek Yu. It's another kind of book, a developer breaking down the mysteries and the philosophy behind their game. I think maybe that title has the most novelty, and in some ways the most authority, because who better to write Spelunky than the creator himself? That's helped us a lot in season 2. A lot of the game community, a lot of the development community that respects Derek so much, really got behind that particular book.

During the second Kickstarter it was hard to predict what would get people the most excited, but what connected most with people was the promise of the Spelunky book by Derek Yu. It's another kind of book, a developer breaking down the mysteries and the philosophy behind their game. I think maybe that title has the most novelty, and in some ways the most authority, because who better to write Spelunky than the creator himself? That's helped us a lot in season 2. A lot of the game community, a lot of the development community that respects Derek so much, really got behind that particular book.

But we're always going to hit different people with different books.

You said you found the Michael Kimball book, and you're likely to follow him because you respect his work as a novelist. Most game developers don't know who he is. People will be reading for different things, and I love it when readers of our books show a certain elasticity. When they can jump to a different book and enjoy those differences instead of saying, "This one's the good one because it does XYZ."

I'm as interested in people as I am in video games. Not just what games are and why they exist, but what they're doing to us and for us, and what does life with video games look like. For Michael Kimball, it was escape. You have to hear this story of childhood trauma to understand what Galaga is for him. We talked a lot about obsession. That's what I grabbed onto as an editor. It's a book about obsession and escape.

I loved his book. Sometimes we talk about escapism as being negative or even destructive, but in his book, he needed something where he felt in control and where he felt some agency.

Agency and mastery are a huge part of life and a huge part of identity. It really can bleed from one thing into another. As silly as it can be for somebody to brag about being really good at video games, it's also really impressive to people who know. I watch speedrunner videos online with only the goal of being wowed by the expertise.

The time they put in and the expertise, it's pretty amazing.

There was a guy who beat Goldeneye, Mario 64, and Ocarina of Time at the same time. He had 3 Nintendo 64 consoles, and he would switch from one to the other. While an Ocarina of Time speech was going on he would switch over to Mario really quick. I think it was about an hour and he beat all three.

It's just so amazing, these subcultures within gaming. How they develop and what they do. And the communities around them are so different within these different subcultures.

I think about it that way too. We talk about gaming as one culture, but it's actually a lot of them that appeal to different people based on which games they love and what they're gaming on. Maybe the most popular game right now is that Kim Kardashian game. I've never played it, but it is a video game. And it's such a huge cultural force.

One of the things I got from Boss Fight Books was a lot of subjective narrative about games and the people who play games. How do you feel about video game writing and subjectivity?

I think objective reviewing of games or anything else is fallacy. Once taste enters the picture, there's only personal taste. There's only subjective experience. Game reviewing is totally legitimate, and even numerical game reviewing has its place. Particularly in the question, ”Is this game good and/or would this game be good for me?” Reviewers try to give taste indicators, but there's so much more that you can talk about.

One of the things I was impressed with when I started doing R&D for Boss Fight Books was how rich and personal a lot of game writing was. Which I just didn't know about for a while. That wasn't my world. I came out of a creative writing scene, did an MFA and wrote fiction for a long time. I was surprised by the richness in a lot of people's writing about games. Both in the depth of analysis and how well they spoke to their own experiences. You know, a lot of writing about games can be writing about childhood or adolescence, or the act of growing up, and those can be really powerful experiences.

I think where things can get really interesting is where the personal and the journalistic intersect and you get to use all of your tools towards a particular goal. You'll find with our books that most of the authors are doing more than one thing. They have these different threads they're weaving together. And at best, the different threads give power to each other.

Hopefully the future of writing about games is as broad and as interesting as the future of writing itself. One thing I and a lot of people would like to see is for video game writing to be less of a world unto itself and for it to be involved with the rest of our culture. That’s one thing I loved about Tom Bissell's Extra Lives. One of the things it does really well, it's talking about games, and it never flinches about bringing in novels or movies or music. It brings the art world together and draws comparisons and makes connections. It's all art, and when we can look at it all together, great creativity happens and we see the most potential.

Another thing I read was Darius Kazemi's "Fuck Videogames", which I'm publishing in an anthology. That piece was all about how Darius had been working on games for a while and relying on that for his dominant form of artistic expression, but he was finding that he had other ideas that could be better expressed in other mediums. The point isn't really “fuck video games” but “fuck thinking you only have to think in one medium.” “Fuck not considering what would be the best vessel for your idea or your emotion or what you want to express.”

While we're talking format, you wrote a book, Fun Camp, and it's the story of a fictional, surreal summer camp depicted in letters and speeches and camp skits and things like that. It draws from all this different stuff to build a whole world, and as you read it, more and more is added to the world as you go. It's one of those books that's more and more rewarding as you go. And now you've got your own Boss Fight Book coming about the game Bible Adventures. Tell me some of the differences, how you felt as a second-time author and as series editor this time.

It wasn't long after I finished Fun Camp that I started getting more interested in writing non-fiction and reading people like John D'Agata and David Shields. In Fun Camp you can kind of see I've got this inclination to vacuum up all of this memory and convention and these different forms and bring them together towards an emotional goal. And for a little while I was trying to figure out what the next fiction project would be.

Bible Adventures has been exciting. When I started the press, I liked the idea of writing one of the books eventually, but I didn't have an idea what that book would be. There are a lot of games I like, but I don’t necessarily have a lot to say about them. I wanted an idea where I could talk about a larger thing at work, something besides just the game itself. And so I thought of these weird, unlicensed Bible games I played on NES. I got them off of this cart of books at the church I went to as a kid. It usually just had Bible picture books and things like that I didn't really care about. Then there were these two games.

Bible Adventures has been exciting. When I started the press, I liked the idea of writing one of the books eventually, but I didn't have an idea what that book would be. There are a lot of games I like, but I don’t necessarily have a lot to say about them. I wanted an idea where I could talk about a larger thing at work, something besides just the game itself. And so I thought of these weird, unlicensed Bible games I played on NES. I got them off of this cart of books at the church I went to as a kid. It usually just had Bible picture books and things like that I didn't really care about. Then there were these two games.

I checked out Bible Adventures and Joshua: The Battle of Jericho. They were kind of fun. They were kind of mysterious. The cartridges were different shapes than the normal games. I didn't understand the difference between licensed and unlicensed, but you had to kind of cram the cartridge into the Nintendo, and you couldn't push it down. They were these weird objects. But honestly, I was used to Christian shit being different from other things. Christian stuff always had this sense of difference. Christian music was different. It had this different language and spoke to different people and had different concerns. There are Christian products like Christian bumper stickers and Christian breath mints. So you would go to the Christian store and everything would be weird and off-brand, and that was kind of the norm.

What I didn't really question as a kid, I was able to come back to as an adult: What were these games and why did they exist?

I found Roger Deforest, one of the guys who worked on the game. He wrote a short narrative about it. I found interviews with some of the other developers on Nintendo fan sites from years ago. But nothing existed that was putting the whole story together in a big way. It really seemed like an opportunity. A story that hasn't been told properly yet, unlike the stories of some other game franchises.

I was able to contact Roger Deforest, and I was able to meet up with [game designer] Dan Burke. The more information I got, the deeper I got into the project.

The same company that made Bible Adventures [Color Dreams, later Wisdom Tree] made several other games, and all of them were weird. As the company went on, Nintendo was dying as a console. Wisdom Tree couldn't really make games for the new generation of consoles because that took more money and more time, so their solution was to convert games that they already made when they were a secular game company. That's how you came up with these games like Sunday Funday. They just took the same skateboard kid from this other game and put a Bible in his hands, even though the game is literally just about a kid who beats up everybody in town. But now, instead of trying to rescue his girlfriend, you're just trying to get to church on time. You have to ask yourself "Why is he murdering EVERYONE just to get to church on time?"

It's sort of nutty. But I feel like, because I came out of that Christian culture, because my dad is a minister, I feel like I understand it. It's a topic I can get my head around. I kind of resigned myself to the fact that I picked a game that would not have nearly as big a built-in audience as other games, and instead I just worked on making the book as good as possible.

That sounds like it fits, though. I feel like the Boss Fight authors respect games and what they do, and at the same time they're willing to admit where the flaws are and say, “This isn't perfect.” They're willing to have fun. That's another thing I see in the books, this running theme of fun. There's a quote you gave to Buzzfeed, and it's "Games have always been art, but for a while we were just having too much fun to care." Can you tell me more about the relationship between art and fun and how that works and doesn't work sometimes?

Fun has a place in art. It's absolutely fine to create art that isn't fun, and it's necessary to create art that isn't fun. Not everything that's important to say can and should be put into a fun package. But there's also huge potential to create art that's important and lasting and legitimate and that's also a blast. A lot of the best books and movies and music that I love are absolutely, really fun. Last week I got to rewatch The Wolf of Wall Street, and that movie's insanely fun. Somehow it’s a comedy that's well over two hours but doesn't overstay its welcome. It shows a really important thing about greed and excess and what greed turns us into. A lot of people are down on that movie because it makes being a greedy stockbroker look really fun. Yeah, being a greedy stockbroker is really fucking fun!

That's the most recent art experience I can think of where the whole time I'm having a blast, and it's great cultural criticism. I can revel in watching what happens and would hate myself if I took part in it.

With the relationship between art and fun, I think a lot of us, when we start writing seriously, we fall into the trap of thinking that writing seriously means we need to be serious in our writing all the time. That we can't enjoy levity, and we can't enjoy a laugh when we're writing.

There are people who would look down on a project like Boss Fight because it's spending a lot of time looking at entertainments that can be more about pleasure than expression or exploring ideas. Not all games are just about pleasure, but certainly some. For instance, Galaga, that's a spaceship that shoots bugs. It's great, it's all you need. So the meaning in that game is the meaning that someone like Michael Kimball puts on it, not necessarily the inherent, in-game meaning. The meaning he puts on it isn't any less important though.

There is a real tendency, if subject matter is serious or written seriously, there’s a tendency to take the material seriously. If there are jokes or really deep humor, I think sometimes people are afraid that's going to release the tension they've worked so hard on. But reality is a mixture.

Right. That's life. All of it. And there's that breakdown of high/low culture. People of our generation aren't necessarily as concerned about that stuff as people used to be. And that's why you have these literary zombie books and that kind of thing. People can be fans of pop art and pop entertainment and still have something important they want to get across.

We grew up in school hearing Shakespeare's stuff was for the masses and kind of low entertainment in its time. And maybe that distinction or that inherent value of entertainment being high or low brow is not the first place to go.

Right. To read Shakespeare is to read SO MANY dick jokes. Incredible amount of dick jokes.

I always wonder how many of my junior high teachers must have uncomfortably skipped by a passage and hoped no one would get it.

In the service of our appreciation of literature.

Okay, I have a few quick wrap-up questions:

Recommendation for a best Boss Fight Book to start with if you're a total non-gamer and interested:

A lot of casual gamers might come to Super Mario Bros. 2 first because a lot of people know that franchise and played that game. That could be a nice entry point. The stuff that ZZT could get into, a certain kind of reader might really enjoy the exploration of culture.

Favorite classic game you wish more people had played:

Crystalis for the NES, which was kind of like the best Zelda clone to come out for the NES. It came a little too late for people to notice. I think SNES was already out by then. But that was a game I really got lost inside of and played so much. Another one was Rocket Knight Adventures for Sega Genesis. Lately, this year, I've been way more obsessed with The Binding of Isaac than any other game.

What are you reading right now:

One of the downsides of this job is when I get deep into edits, I stop reading other books, which is kind of a bummer. But I'm into Gilead by Marilynne Robinson.

If people are interested in submitting proposals to Boss Fight Books, what do those opportunities look like, and what are some specific tips or things to avoid?

I do plan to open up submissions sometime mid-2015. What I'm mostly looking for is somebody who has something they really want to explore. There's the game itself, then there's the writer's vision. What they would do with the game and why it demands a book. All of our books are about the game and another thing. I think I'm looking for a really clear communication of what that angle is. Really helping me see what that book could be.

Make it real to me. Show me the book’s inevitability.

You can find Boss Fight Books at BossFightBooks.com, where you can order all of their titles, including Continue? The Boss Fight Books Anthology.

This author's personal recommendations from Season 1:

Earthbound for anyone who grew up with siblings.

Chrono Trigger if you know what I mean when I talk about "localization."

ZZT for readers who like stories of identity and atypical roads to adulthood.

Galaga for fans of MIchael Kimball. Which, seriously, you all should be!

Jagged Alliance 2 for those interested in the business and tech side of gaming, which is truly fascinating.

Super Mario Bros. 2 for a great history of Nintendo and the world's favorite plumber.

About the author

Peter Derk lives, writes, and works in Colorado. Buy him a drink and he'll talk books all day. Buy him two and he'll be happy to tell you about the horrors of being responsible for a public restroom.