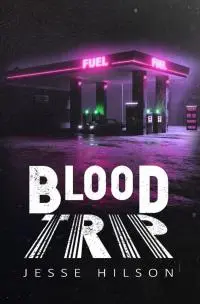

Photo courtesy Jesse Hilson

Writers often see how little they can get away with, condensing all their reductive intention into a “brand.” While this may take root in our attention deficits, we may never know who the real writer is. For instance, it boggles me that more fiction writers don’t write poetry – it’s the easiest way to show the world who you really are. And if you can pull it off, it’s the best way to show your economy of language, not just your command. On the other hand, I maintain poetry is the most difficult form to navigate; to write it well enough to float above the masses' attempted dredges often takes years to perfect, contrary to many who think it just requires breaking meter-less prose into verse (if you don’t know who you are, I sure do).

Since we first began hearing of him around 2020, Jesse Hilson has never been anything less than exactly who he is—not just a novelist, short story writer, confessional non-fiction/cultural essayist, poet and cartoonist, but with this wide range comes a humility that’s difficult to replicate; a non-performative sincerity you just can’t make up. From his debut noir novel Blood Trip (Close to the Bone, 2022) to his near daily Substack insights into modern literature and his struggles with mental illness, Hilson’s writing is both intense and introspective across the board.

With his debut poetry collection Handcuffing the Venus DeMilo (Bullshit Lit) released this month, the hard-to-pin author compiles a large slice of the cyber-poetry he’s been sneaking into our subconscious online into a cohesive physical statement that reads like haunted psychological scripture or late-stage-capitalism John Berryman.

Jesse, you and I have often discussed a common trajectory, a condition we’ve called “genre refugee” where we’ve cut our teeth in genre and enjoy the freedom to return there at times, but also turned off by its restrictions of form and cliques constructed from its rigidity to define itself. Can you tell us how you started in this lit landscape and where you are now?

After some initial contortions writing and submitting poetry online, I had this feeling in 2019 that with dollar signs in my eyes I could try to be a crime novelist. I’d written a few crime/mystery novels and I felt like that was something I could continue to pull off in the future and maybe get paid. As I reentered Twitter after years away, I started exploring the outline of the map of the indie crime lit community and quickly began apprehending a certain kind of tacitly corporate industrial superstructure to the genre writing community in toto: internal politics, cop mentalities, clique-like formations, and the pervasive negative effects of constant salesmanship.

In the closing days of 2020 I got a crime novel accepted by Close to the Bone in the UK and there I met you and other label-mates like Max Thrax, and right about this time certain scandals or divisions which can only be described as political struck the indie crime lit world and specifically our publisher. I, being new, didn’t know who anybody was or which side to take as people claimed allegiances, or whether it mattered as no one with a major profile in indie crime knew I existed. I stayed with my publisher but the drama left a bad taste in my mouth. Also around this time I became aware of some less overt, genre-evading publications in hidden-away underground cubbyholes of Twitter lit, like Misery Tourism. I started migrating to attending their weekly online reading series, Misery Loves Company, and I saw there was this other literary culture happening that was looser, more apolitical, more adventurous, funnier, and honestly just friendlier. The stakes were different; it was more about art than about chasing money. I still consider myself to be capable of genre writing, but this other parallel track of “cyberwriting,” as it’s somewhat tongue-in-cheek been called, is appealing to me as a place where, if I am indeed doing it, I feel like my punches and karate kicks have connected more.

I know you’re working on a non-fiction project chronicling this sort of vaporous scene we participate in. Would you describe this fringe scene to be more a movement that can be defined, or more of an era that has all to do with outside social/political developments; maybe a reaction to such?

You’re right, it is vaporous, and defies definition. To my way of thinking, whatever it is, it is “post-genre,” or maybe “extra-genre,” and yet not quite literary per se. The fringe quality of this scene has antecedents in the alt-lit of yesteryear that I wasn’t present for, so its pedigree contains genetics mysterious to me which might be chronicled one day by literary historians with broader reading habits than mine.

As far as sociology or politics, it seems to pull something from being largely an offspring of the Internet, and whatever bespoke “home-brew” quality it has seems to have only been fermented stronger by the internal exile of writers driven into isolated lockdown by the coronavirus, and possibly driven onto each other’s radars in a way that wouldn’t have happened if we had just participated in our local scenes IRL. I think this is its major characteristic as far as I can tell. I’m more focused on writing book reviews at the moment—books as objects perhaps being a more metaphysically privileged literary culture than the “vapor” of online lit mag ephemera—but if I were going to do a non-fiction chronicle of this movement, I would maybe like to write something like Malcolm Cowley’s Exile’s Return, which was about literary figures in the 1920s like Hemingway and Dos Passos spending much of their time in self-imposed exile in France. But in the 2020s the mass exile is not in Europe, not geographic, but onto our laptops or phones.

How early in your life were you struck by literature? Was the first work that stunned you the same one that compelled you to become a writer?

I’ve always dreamed of being a writer since being a little kid. When I was a teenager I found myself pouring my heart into poetic love letters to girlfriends and finding I could express emotion and move women into giving me love in return, but in a more permanent, less crassly transactional sense I was probably just showing off for myself. Inevitably as a Gen X young person you encounter the Beats and I discovered the wild, febrile imagination of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, and I saw that book as an artifact with a forbidden, perennially underground aura that was badass. Then like a lot of people my age I fell under the shadow of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest in 1996, which left a massive novelistic dent in my brain, a fatal head injury, and it’s been a definite effort since then to try to get out from under that writer’s shadow and influence. It’s taken decades, and I’m not sure the extrication is fully complete yet, or ever will be.

I’d have a difficult time deciding on a favorite Hilson piece since you’re so prolific, but one piece that burrowed so deep into me was your CNF essay “French-Kissing the Light Socket.” As hallucinatory as it is, you somehow made this origin story of “mental illness” completely relatable; how it can be such a fine line between illness and well-being once that veil is pierced. When I read it, I felt you were describing a legitimate religious moment—isn’t that what we are all searching for? What is your view of this “veil” and what is it keeping from us? What are the dangers of going beyond it?

The cliché about the connection between mental illness and creativity I think has become a kind of shorthand by which people (who may not have been touched by either, really) can evade a true understanding of the value of the human mind’s output. This might be gibberish, but I think one of the roles of the artist, in this case the writer, is to go on reconnaissance missions to far-off places where other people aren’t able to go, and to bring back reports to the tribe that could conceivably reveal things of spiritual significance or inner utility that science and rationality can’t provide—otherwise hidden blueprints for how the cosmos, mind, soul, or an absconding godhead operates. Sometimes such information is disturbing, with an unhinged prophetic quality or an alien beauty that the tribe might want to reject, or can’t understand. And the writer’s job is to try to authoritatively describe it and often he fails. Maybe it actually is useless personal mythography, something delusional: the writer has gone too deep into the ghost territory and can’t resurface into the realm of mundane things to make the report. He is mumbling in a solitary, foreign language now. All that I’ve been saying sort of presupposes that the writer is supposed to “make themselves useful” to society and serve the readership as a scout. To do their duty. Which might not always be true. Maybe to the writer the ghost territory becomes more hospitable than the home village of sanity and health.

Do you think a prose writer will always be improved by writing poetry? Why do you think more fiction writers don’t practice poetics? Is it just as important to edit/revise poetry as it is prose? What’s the typical amount of time you’ll spend on a piece of poetry?

My conception of a man or woman of letters is someone who can operate on multiple levels and can create writing that travels at different speeds for different needs. The flexibility of switching between modes of language like poetry and prose is helpful to the writer in every mode, I think. Sometimes the transmission just comes through as a poem and it can’t be helped, and to try to thicken it into a short story or a novel or essay would dilute it or wreck it, and vice versa. Knowing when to compress and when to stretch out, when to dramatize and when to be pithy, is part of this flexibility. Sometimes it’s just showing off, I admit. Poems take days to weeks to compose but sometimes (maddeningly) years sitting in folders to gather the magical properties necessary to project them outwards into someone else’s field of vision. If that’s your thing.

My conception of a man or woman of letters is someone who can operate on multiple levels and can create writing that travels at different speeds for different needs. The flexibility of switching between modes of language like poetry and prose is helpful to the writer in every mode, I think. Sometimes the transmission just comes through as a poem and it can’t be helped, and to try to thicken it into a short story or a novel or essay would dilute it or wreck it, and vice versa. Knowing when to compress and when to stretch out, when to dramatize and when to be pithy, is part of this flexibility. Sometimes it’s just showing off, I admit. Poems take days to weeks to compose but sometimes (maddeningly) years sitting in folders to gather the magical properties necessary to project them outwards into someone else’s field of vision. If that’s your thing.

You’re also a committed cartoonist. Did you start by doodling or were there specific artists who inspired you? What can this format do that literature cannot, beyond the obvious visual element?

I was a terrible doodler in school when I should have been taking notes. I liked making comics to make my friends laugh, drawing naked ladies. Also, drawing while stoned is easier than writing. I spent countless hours as a youngster getting “lifted in the name of hieroglyphics,” listening to ambient/dub/hip hop, and drawing trippy cartoons. Later when I focused more, I found a strong appeal in the monochrome psychedelia of underground cartoonists like Robert Williams, Paul Mavrides, and Skip Williamson, or just more mainstream comics like Sergio Aragones’ Groo the Wanderer, with his breathtaking panoramas full of elaborate by-play of detail and extra characters. Again, like the flipping between poetry and prose, this fits into my notion of being well-rounded and, just as different muscle groups are exercised at a gym, you should be able to do multiple types of art. Because when drawing dries up, let’s say, you can cycle to another medium like poetry or fiction, while you hope for the drawing pencil to come back. The point is to try to maximize creative flow. Because it’s when it isn’t flowing that you feel like stepping in front of a train. Therefore I think in some ways switching formats could be more for the artist’s survival than for the viewer’s or reader’s benefit.

What would you tell a young writer just starting out in this often intimidating landscape? What would you have told yourself in your twenties?

I might have told myself to be patient. That success is something that might potentially come later. In my twenties, I always hated it when I heard people say “you as a writer will likely have nothing important or original to say when you’re twenty-two, you haven’t yet learned a fucking thing about life, you have no substantial story to tell.” I’m an older man now and in spite of the average age of my online peers skewing younger, I feel like it’s more like my time to speak now than it was when I was younger. Also, I would advise somebody younger to, sure, aim for success but also to develop a healthy sense of scope for defining that success. I can already tell that the people who will dig my writing or artwork will be a smaller circle of perhaps a more “hip underground intelligentsia who would really get it” (Robert Williams’ words) and it probably won’t really pay the rent. And that’s alright.

Another thing I’d advise, and this is more of a life thing than an art thing necessarily, is to gain a good sense of how to organize time and energy so you can do art and yet do normal life things like pay attention to a career or a family. I’ve lost both those signifiers of “the good life,” and I think being smart about prioritizing multiple aspects of life could have made me a happier individual. Finally, I’d say: Your imagination as an artist can produce wonderful beauty but it can also produce horrors and fears that will utterly conspire to waterboard you and destroy your life. So make peace with your imagination.

Get Handcuffing the Venus De Milo at Bullshit Lit

Get Blood Trip at Close to the Bone

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.