Author photo courtesy of Max Thrax

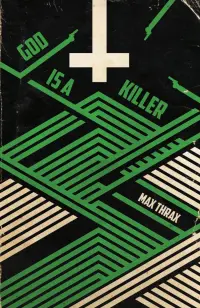

Trickling out ruthless indie-crime short stories since 2020, Max Thrax has been consistent in writing stark, brutal noir that wastes no words. His debut novel, God Is A Killer (Close to the Bone, May 27th), shows his detached yet intimate style is on brash display, following the intricate calamities of a religious cult leader clashing with the law in the methamphetamine underworld. Thrax doesn't insult our intelligence—he knows over-explaining can be a deterrent to full-immersion. Instead, he throws us into the foreign matter where we must sink or swim as readers. His masterful dialogue offers just the right amount of info to keep the fraying threads of human nature burning. Thrax is also the fiction editor for Apocalypse Confidential, an online journal where crime, transgressive, and sardonic humor will often converge.

God Is A Killer is such a specific, idiosyncratic novel, especially for the noir/crime fiction genre that can unfortunately often be very paint-by-numbers. What inspired the story and most importantly, the unique way you chose to tell it?

God Is A Killer began with the character of MacDougall. In the first draft, he was a fanatic who believed the government had buried alien skeletons across the country and felt it was his duty to excavate them. I kept the fanaticism. After a few more drafts he became the leader of a doomsday cult, inspired in part by David Koresh and the Branch Davidians.

I came to crime fiction as a classic Ballard/Burroughs fan, and was inspired to write crime by Jim Thompson. Both noir and so-called transgressive fiction have roots in writers like Conrad, Dostoevsky, and Hamsun. I like playing around with those connections.

In your opinion, what is missing today in noir/crime fiction, and what voids do you see yourself filling, best case scenario?

I try to recapture the energy of classic pulp and noir fiction without replicating the form. If noir gets itself in trouble, it does so by trying to be optimistic or respectable.

Besides being a novelist and short story writer, you are also a noir poet. Why is noir poetry just now seeing more light of the day?

Much of the attention noir poetry gets is due to Stephen Golds, who was Close To The Bone's poetry editor when they accepted my manuscript. He brought a number of great poets to the press, and more than anyone is responsible for the genre's emergence. Like lyric poetry, noir deals with heightened, often negative emotion. They have similarities in the first place.

Your novel deals with both meth and a religious freak, which spoke to me immediately— it made me recall the number of people I knew growing up who either did so much meth that they saw God, or they quit doing meth and defaulted to religion to redeem themselves. At the end of the day, it appeared God was actually the thing we couldn't escape. How do you see the correlation between these two?

Your novel deals with both meth and a religious freak, which spoke to me immediately— it made me recall the number of people I knew growing up who either did so much meth that they saw God, or they quit doing meth and defaulted to religion to redeem themselves. At the end of the day, it appeared God was actually the thing we couldn't escape. How do you see the correlation between these two?

Meth and religion are ways of escaping everyday life. The difference is that meth provides an escape located entirely inside the body, which sooner or later extracts its revenge. Religion is a way of recognizing the sacred in everyday life, of understanding things in a greater, "supernatural" context outside the body, physical pleasure, and immediate human desire. I was raised in an Eastern Orthodox home, where I was made to understand the distinction between chronos (secular time) and kairos (sacred time).

What is it about New England, where you're from? How does that area inform noir for you?

For some reason or another, New England has always seemed apocalyptic—it's not a coincidence Lovecraft came from Providence.

Most of my fiction takes place in Boston, which has a long and distinguished history of organized crime. God Is A Killer differs in that it's a rural noir story set in the White Mountains. There is plenty of menace and darkness in the woods of New England, which the Puritans of The Crucible saw as Satan's citadel.

You spend a lot of time online musing on art, especially interesting vintage international pulp novel covers. What inspired the abstract cover art for GIAK?

The cover was Matthew Revert's idea. We both have a fondness for Polish poster art, as well as maverick book designers like Romek Marber and David Pelham. I had complete trust in Matt to deliver a great design, and he did.

As the fiction editor for Apocalypse Confidential, can you describe the kind of work you're looking for? Has being on the other side of the submissions portal altered your outlook on the submissions process?

Apocalypse Confidential is a portmanteau of Adam Parfrey's Apocalypse Culture and James Ellroy's L.A. Confidential. We're interested in the underworld, "the occult" — in the sense of something hidden. This lends itself as much to genre as to literary fiction. We're no strangers to pulp or samizdat.

As a writer, I try to be professional about submissions and that carries over to my work as an editor. Being part of Apocalypse Confidential is rewarding because we often get submissions from very talented yet under-published writers. Before the mag was founded, it's doubtful they had many other places to submit their work.

Since this is your debut novel, what advice would you give now to a younger version of yourself?

I wouldn't say much. Keep working at it. Above all, make sure you write something you would want to read.

Get God is A Killer at Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.