Last August saw the release of A Man of Shadows, Jeff Noon's first novel to feature down-on-his-luck private eye John Nyquist. Now, less than a year later, The Body Library comes nipping at its heels. In this psychedelic sequel, our protagonist awakes in a room next to a dead body, an event that triggers a murder investigation set in a city infected by story.

For A Man of Shadows, Jeff wrote an enlightening ten part series on the creation of said novel, which we hosted here at LitReactor. It is a rare, in-depth look behind the curtain of an author's process. For The Body Library, we went easy on Jeff—a simple battery of probing questions. He was kind enough to indulge our queries with the usual wit and charm.

You disappeared for a while but now you’re back with a vengeance. Has this Brave New World of publishing taken some getting used to? How has your place within it changed?

After Falling Out Of Cars, I took some time out to try and break into screenwriting, and suffered the usual set of frustrations. After a number of years I felt the urge to get back into writing novels again. During my time away, the whole eBook thing had come into being, so I took the plunge into that, and wrote a new novel, Channel SK1N, which I published myself along with a good chunk of my backlist. I then did Mappalujo for Tickety Boo Press, written with my friend Steve Beard, a novel created using a collaborative game process that Steve and I invented. We’re always inventing things! So I was producing work, but on the more experimental end of the spectrum. And then when Angry Robot got in touch, asking for a novel, I just went full on into storytelling mode, and John Nyquist was born. I’d always wanted to create a private eye character, a noir thriller type, because I love those old books so much, and this was my chance to place that kind of character into a weird, avant-pulp setting. And for the first time in a long time I’ve been going to sci-fi conferences, so I’m meeting other writers, readers, publishers and so on. So all that is really good: I feel like I’ve crawled out of the shadows, into the light.

So then, what’s changed? I’ve noticed a transformation in the content of sci-fi novels: on the whole, authors seem to be dealing now with massive themes of time and space and philosophy and political upheaval and trans- and posthumanism, and so on. This is interesting to me, although it’s far away from my own approach, which basically grows directly out of contemporary British life, twisted and mutated, seen through a broken looking glass. I was aware of this at Eastercon this year: my subject matter was quite different from that of most of the other writers at the event. I guess I’m still following the cyberpunk impulse to some degree: weird city life, making the familiar strange, just one or two tech inventions but mainly experienced at the street level and then pushing that original impulse into bizarre extremes. I had a few discussions with other writers and readers about this at the con, about the different pathways that sci-fi and fantasy can take. Of course there are exceptions, such as Matt Hill’s Graft, which also deals with the modern-day urban experience, exaggerated in a very interesting way. I would like to see more of that approach, although I do love the giant concepts that are the current fashion.

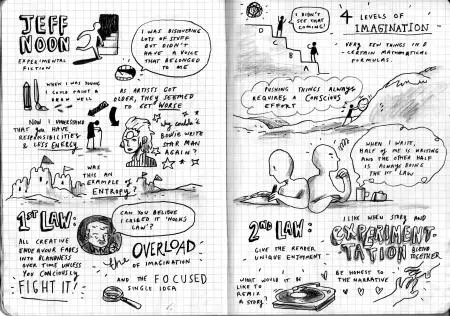

You’ve spoken publicly about what you call “Noon’s Laws,” which deal with creative entropy and how to combat it. What was the genesis of these laws and why are they necessary?

This is really embarrassing to me! And this is the first time I’ve ever written it down. So here goes. When I was young I invented a law that I’ve followed ever since. Every single word, story, concept and narrative arc I’ve ever written is governed and created by that law. I am not exaggerating when I say this; I am speaking the simple truth. I was in my late teens, studying A Level art, and exploring for the first time lots of different kinds of music, novels, plays, films, etc. and in my arrogant youthful mind I came to a conclusion, which was this: as artists get older, they get worse. They get blander. That was the word I used. How terrible to say that now! It pains me to even mention it. But there it is: many of the artists and writers and musicians I loved seem to run out of ideas, or passion, or the urge to surprise, as they got older and I was puzzled by this, as a young man. What was happening to them? Why couldn’t David Bowie write songs as brilliant as Star Man or Ashes to Ashes all the way through his life, why does it become more difficult later on?

This is really embarrassing to me! And this is the first time I’ve ever written it down. So here goes. When I was young I invented a law that I’ve followed ever since. Every single word, story, concept and narrative arc I’ve ever written is governed and created by that law. I am not exaggerating when I say this; I am speaking the simple truth. I was in my late teens, studying A Level art, and exploring for the first time lots of different kinds of music, novels, plays, films, etc. and in my arrogant youthful mind I came to a conclusion, which was this: as artists get older, they get worse. They get blander. That was the word I used. How terrible to say that now! It pains me to even mention it. But there it is: many of the artists and writers and musicians I loved seem to run out of ideas, or passion, or the urge to surprise, as they got older and I was puzzled by this, as a young man. What was happening to them? Why couldn’t David Bowie write songs as brilliant as Star Man or Ashes to Ashes all the way through his life, why does it become more difficult later on?

Well, I’m 60 now, and I understand more the pressures of life, and responsibilities, and sadness and loneliness, and endless household bills, and so on and so forth; but back then, I didn’t get it. I was just confused by it. And one day this really weird piece of reverse logic came into my mind: if I could discover what it was that made artists get blander as they got older, and then reverse that process, and apply that reversed process to myself, well then I would get their discarded energy, and I would become brilliant! That was it. Crazy, crazy. Nineteen years old thinking this stuff. Just crazy! But I did it, I worked it all out, in my mind. It was all to do with entropy, and how the human mind is affected by that process just as much as any other machine. But the mind has this one great advantage over other machines: it is conscious, it can make a conscious effort to reverse the process of entropy, just as in a gym, we’re consciously trying to do the same for the physical body. So I squeezed all these thoughts into one simple idea: that all artistic endeavour fades into blandness, unless you consciously fight it. And then I made that into a Law by adding a phrase on the end: therefore, consciously fight it! I named this, again with the arrogance of youth... Noon’s Law. Ha! Let me repeat it: “All artistic endeavour fades into blandness unless you consciously fight it. Therefore, consciously fight it!” It sounds awkward, stating it baldly like that. But this is what I put into action. And I called it a Law because it had to be obeyed; it’s not a rule or a guideline, it’s a goddamm Law. I can’t do anything else but obey it. And ever since I have followed that law to the very best of my abilities.

Next, I came up with the concept of the four levels of imagination. It’s way too complex to go into here, but by applying the Law to my work in a very conscious way, I found that I could first of all generate lots of ideas, and secondly, work on those ideas to find the even better idea hiding behind or within the original thought. I was in my early 20s, when I was thinking along these lines. Not yet a writer, but seeing myself as a visual artist, a painter, or maybe a musician in a band. I’d worked out that when we come up with ideas for paintings or plays or novels or songs, we tend to play that idea out. And that’s it; the work grows from that process. The Law urged me not to do that, not to play out the idea, but to examine the idea itself, and to push and push and work and work at it, with a conscious effort, until something more startling, more exciting was found. Of course it doesn’t happen all the time, but the more I did it, the easier it became. And even then, once I’d come up with this better idea, the Law would be urging me on, a voice in the ear: more, more, keep going, explore, don’t stop now, more, more, more! It’s quite relentless. Around this time I started to jot down my ideas in notebooks. I found these books recently: nine volumes, one idea per page, each one numbered, over 1500 ideas in total.

So, there I was, with my Law in place, working at it everyday, never letting it out of my mind. A few years later I added a second law to the first, which is all about writing for the reader’s pleasure. If you look at my first novel Vurt, you’ll see it’s dedicated to Nick. Nick was my best friend in Manchester, and I decided that I would write a book for him to read: that was my guiding light through the process of writing: what would Nick like to happen now? So the first formulation of the second Law was very simple: “Write for the reader’s pleasure”. But there seemed to be a mismatch between the first and second laws, in the sense that the first is all about expressing yourself in a highly individualised manner, while the second is all about pleasing the audience. So I added the word unique to the second Law. And that one now states: “Give the reader unique pleasure.” The word unique feeds directly off the first law, and in turn feeds back into the imaginative process, creating a feedback loop. I can feel this feedback loop at work in my mind constantly, as I’m writing, or playing guitar, or during any kind of artistic pursuit. A novel only comes to life when the reader reads it: that’s the ultimate interface, that moment as the eyes scan the pages, taking in the words, creating meaning in the head. The second law is all about that moment, fuelling or feeding that moment, keeping it alive. I am totally focussed on that reader/writer interface, as I write. That is the area of pure intensity, much more than the keyboard, the screen, or even my inner mind.

This is how the Laws work in practice: when I’m working my mind splits in two – one half is writing as normal, working on characters and plot and suspense and twists and prose style, etc. And the other half of my mind is just repeating the two laws over and over and over again, and again, and again, never-ending, nonstop forever. It never ends! I guess it’s a kind of madness, but there it is, this is how I write. Style, content, whatever: all are governed and created by these two laws. Every single word and idea. Absolute fact! And it’s never become a subconscious act: it’s always something I’m aware of, always an active, deliberate process.

I have kept this secret for 40 years, mainly because I find it all very embarrassing to talk about, but a few months back I was invited to Nottingham to speak to a group of young people about writing, and I decided, because they were around the same age as I was, back then, that I could describe the law to them, and maybe it would make sense. So, for the very time in my life, I revealed the two laws, and the importance of conscious effort. A lot of the attendees came up to me afterwards, and told me how inspiring the talk was, which was weird: it’s such a personal thing for me; it’s not something I could ever imagine speaking aloud. But the cat is now out of the bag! And then a few days after the talk a drawing was sent to me via Twitter, created by one of the people in the audience, and this drawing sums up the process very well; in fact, brilliantly!

Click to enlarge. Image copyright B. Mure.

How does experimentation fit in? How has your approach to writing changed since your debut?

I still experiment with words and content and form, all the time. Sometimes on Twitter, sometimes in books or short stories. My story, “Mercury Teardrops”, included in NewCon Press’ Best of British Science Fiction 2017, was constructed out of rock song lyrics, mutated and bent out of recognition, and then twisted into a new sci-fi shape. I love doing that kind of thing. Mappalujo is a very experimental book in its form and structure, even if the plot delves deep into a pulp expression. The combination of storytelling and experimentation will always be my pursuit, in different ways at different times: that mix is always there at the root, even in my most straightforward works.

It’s been 25 years since Vurt was published, and that’s a long time, but I don’t notice any great change in my overall approach over the years. It’s mainly a process of gradual change. There have been upheavals, like the sudden discovery of remixing prose, but even there the experimentation fed directly into narrative, into character. I’m always searching for the moment when the narrative cracks open and a new kind of expression emerges. I liken it to forcing craziness into a grid system: it doesn’t fit properly, it squeezes out, and where it doesn’t quite fit, this is where the richness lies, where the experimentation takes place. That’s the golden moment. Pounce!

Your original contract with Angry Robot was for two books: A Man of Shadows and The Body Library. Have we seen the last of John Nyquist?

There is definitely one more; it was always seen as a trilogy. I am already formulating ideas for that, and they are getting crazier by the day. Nyquist does seem to get into some seriously weird trouble! I like him, though. I want to follow him, to push him into new areas, into new danger zones. I want to see how he reacts to strange processes and objects. This is one of the great advantages of sci-fi and fantasy, that our characters get to go through such bizarre happenings. After that book, I don’t know. First of all he has to survive the third book, which will always be in doubt, I imagine, right up to the very last page of writing. We will see. It’s an adventure.

Was the second Nyquist Mystery easier to write?

It was a completely different process from the first one. A Man of Shadows took on its shape and theme over a good number of years, totally on spec; a lot of it written when I was lost in Screenwriter Land. It went through various drafts, sometimes completely different from each other. Just a lot of different approaches to the same basic plot and location idea. So when I got a chance to join the Angry (but lovely) Robot squad, I had another look at the manuscript. I came up with some new ideas that seemed to make the narrative work better. I rewrote parts of it, all with the editor’s help, and did a further draft, beginning to end, and so eventually it became the finished book. Maybe from first idea to final draft it took six or seven years, on and off.

In contrast The Body Library had to be written fairly quickly. I used to put out a novel a year, back in the day, but it’s not something I’ve tackled recently, so it was quite a shock to the system. But I persevered. A Man of Shadows is set in an alternative England of 1959, so as a starting point I had a look at events that happened in the real world in that year. The one that intrigued me was Brion Gysin discovering the cut-up technique, and showing it to William Burroughs. The plot of a novel called The Cut-Up Method started to emerge in my mind. I envisioned people chasing after a book of cut-up texts that acted as a kind of magical talisman, a book of spells, but non-linear spells, you know? It was then easy for me to imagine Nyquist struggling against such a thing, I could see him entangled in these spells. At some point the title changed to The Body Library (itself a mini cut-up of Agatha Christie’s The Body in the Library). So then I started plotting, and writing, working quickly on the first draft, kind of improvising from one chapter to the next, but with an overall plot in mind. The nature of the story took me over, I think, and the words flowed as though I were infected with them: the same thing happens to Nyquist. So I felt bonded to him. And towards the end of that process I realised that I was writing a love letter to language, to story, to words: my chosen medium, the ever-shifting landscape in which I live and work.

About a year ago I read you were working on selling a straight crime novel. Has there been any movement on that?

About a year ago I read you were working on selling a straight crime novel. Has there been any movement on that?

There has indeed. My first ever crime novel has been bought by Transworld. It’s still being edited, so I’m not yet sure of a publication date. It’s called Slow-Motion Ghosts. It’s set in 1981, in London and Hastings, and deals with the long-term aftermath of a rock star’s suicide in 1974. So a lot of it is to do with music, and the idea of a person’s public image taking on a life of its own, and also with a complex, imaginary world created by a bunch of young teens. These are subjects and themes I’ve already tackled in my sci-fi work, so there’s a definite connection between the two genres, in my mind. But this one is grounded in reality, and the language reflects that: it’s a bit more brutal and pared down than my SF style, as befits the mood of the times, the early 1980s. It was a project that crept up on me by surprise: I never expected to be writing a straight down the line crime novel, but once an idea takes you over that’s it: you have to write!

A while back you wrote a manifesto on science fiction. You’ve said you don’t read much sci-fi these days. Have you moved on? How does the manifesto relate to Noon’s Laws?

I used to read sci-fi all the time, but after Vurt was published, I found that quite unconsciously I was no longer reading within the genre, especially British sci-fi: it was almost like I wanted to isolate myself from influence, and just plough my own furrow. I know that some other writers do the same thing. But I have read a few sci-fi novels over the years, and I feel that I might well be coming back to the genre, as a reader, these days. I recently reread the Strugatsky Brothers’ Roadside Picnic, which I loved even more than the first time.

The manifesto refers to avant-pulpism, which is a bringing together of techniques and content from both experimental art, and from pure sitting-around-the-camp-fire storytelling. Everything I do is in someway related to this merger. The Body Library especially seems to grow out of the basic concept of merging narrative drive with more imagistic or fractured techniques. But the two Laws go deeper than that; they go back to my youth, when I didn’t yet have a voice or a style of my own. They are the wellspring. Ideas like avant-pulpism and metamorphiction and the “grain web system” and dub fiction and the Mappalujo engine, and all the other things I’ve been experimenting with over the last decades, are more to do with me inventing processes to match the world as I see it around me. It can be summed up quite simply:

Form is the Host. Content is the Virus. Infect! Infect!

The dream in Vurt, music in Needle in the Groove, Time in A Man of Shadows: in all these books the subject matter in some way infects the characters, as well as the language and style of the book itself. Nyquist in The Body Library suffers the consequences of that infection, when narrative takes him over, and he merges with the story he’s pursuing. He re-emerges on the other side, changed utterly by the experience. This is, to my mind, the prime reason for narrative art: to depict human change in terms of a story.

About the author

Joshua Chaplinsky is the Managing Editor of LitReactor. He is the author of The Paradox Twins (CLASH Books), the story collection Whispers in the Ear of A Dreaming Ape, and the parody Kanye West—Reanimator. His short fiction has been published by Vice, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Thuglit, Severed Press, Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing, Broken River Books, and more. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @jaceycockrobin. More info at joshuachaplinsky.com and unravelingtheparadox.com.