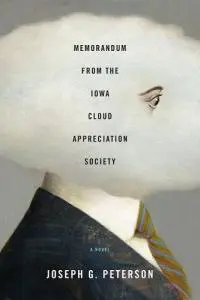

Image via University of Iowa Press

What does it mean to be “one of the Windy City’s best kept secrets?” Maybe the more important question is how does it feel? Or what is it like to create acclaimed work despite, or in spite of, such a descriptor? This description is in reference to Chicago author Joseph G. Peterson. Peterson has penned a number of acclaimed novels, yet is still somewhat of a secret, despite, or maybe in spite of, those of us who admire his craft and champion his work. Upon the publication of his ninth book, the novel Memorandum from the Iowa Appreciation Society, which NewCity writes, “masterfully weaves the restless meanderings of the mind of a solitary traveler yearning for connection and home and validation for his life choices,” Peterson and I connected to talk about the book, the isolation so many of his characters experience and how he defines success.

Please introduce yourself and please share the pitch for your new book.

Memorandum from the Iowa Appreciation Society tells the story of a traveling salesman, Jim Moore, whose sales territory is small in margin but vast in territory, covering the continental forty-eight and parts of Canada. In this book, Jim Moore is stranded in a Northeastern airport because blizzard conditions have stranded travelers. The book takes place while Jim Moore sits at the airport gate contemplating his life, the fellow travelers around him, and the world that he has found himself in. Occasionally a Woodsman arrives from the mysterious fathoms of his imagination and leads him deep into the wilderness of his own mind where he confronts his doppelganger wearing a red flannel shirt. Other times, while waiting, Jim Moore has wayward encounters with his fellow travelers and they too awake in him a sense of his own mysterious humanity and they also offer, if fleetingly, and then withdraw something Jim Moore desperately longs for: human connection.

I have so many questions, however before we continue, can we pause here briefly so you can introduce yourself?

I’ve published nine books that deal with the declining fortunes and emerging catastrophes of men. My work largely deals with men who have lost their place in the world: they’ve fallen out of the economy, they’ve lost their place in community, they’ve fallen out of family and indeed many of my characters don’t want to participate even if they are asked to. Many of my characters deal with social isolation, homelessness, gun violence, alcoholism, suicide, and difficulties fitting into and succeeding in the workplace. That being said, my characters seek meaning and beauty in their lives, and sometimes they find it–and also, for the reader, there is humor in my work.

I’m going to return to Jim Moore, as well as your prolific output and career, and definitely the subject of isolation, but first, why men, why do they, we, command your attention?

I want to make clear that there are women and children in my books as well, though the primary focus of my books so-far-to-date has been on men who might be defined as failures or losers. The men in my fiction have failed at putting their lives together and they are losing as a result. Why do they command my attention? I am one of those writers who doesn’t pick my subject or story, rather the subject and story—the voices of my characters—pick me. Now that I have a large body of work behind me, I can see that in my work there is a consistency of vision and an analytic focus on this theme of the “losing male.” David Brooks recently wrote a NYTimes Op-Ed piece called, “The Crisis of Men and Boys.” The crisis that he describes is in fact the subject that my whole body of work explores. Interestingly enough, there seems to be not a lot of interest in this subject, and I’m guessing there probably isn’t a lot of sympathy for the plight of loser men who have been pushed to the margins of our culture. We remain a culture that values and obsesses over the success story.

Building on this last point, “We remain a culture that values and obsesses over the success story,” what is it about our culture do you believe makes this so, and given comments such as those by Kirkus Reviews that you are “One of the Windy City’s best kept secrets,” this despite the strong response to your work, how do you define success for yourself?

That’s a good question, Ben. For some reason that I can’t explain, I’ve always thought of myself as writing against the rags-to-riches Horatio Alger narrative. According to Wikipedia, Horatio Alger wrote “young adult novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security and comfort through good works.” I have never been interested in writing this type of story. I am more interested in exploring what it means to a person who fails to make their rise to middle-class security. I want to know and describe the existential pain that these sorts of persons might experience through failure. I also want to explore the possibilities for meaning that a person might find in a life that fails to achieve culturally approved modes of success and status. Success for me as a writer comes if I can accomplish telling the flip-side of the Horatio Alger story in a way that causes my reader to empathize and think about what people pushed to the margins of our society might be feeling and experiencing.

Which leads us back to Jim Moore, the protagonist in Memorandum from the Iowa Appreciation Society, who one could argue has achieved middle-class security, yet seems to be struggling with all he’s had to do to get there and all he has lost or missed along the way. Am I reading that correctly, and if so, how/where do he and his choices fit in the literary universe you’ve been crafting across your career?

Yes, Ben, you are correct. Jim Moore is an incredibly hard worker. He is a worker with an almost heroic sense of dedication to his job and duty to his company. No matter what his boss asks of him, no matter how far he is asked to go, Jim Moore complies without question and heads off as told. Along the way, he has amassed a vast territory that keeps him constantly on the go, and he is always in competition to be one of the top sales leaders of his company. That being said, all of this success at work hasn’t translated to a good life. Jim Moore is too busy to rest. He travels too much to be home. And all of this travel and work has robbed him of the opportunity to make lasting social connections that come with being home-bound. He has worked himself into a state of success within his company, but he has failed to find lasting human connection in friends or family. A colleague with whom he has a brief affair points out to him that the job he has is rigged against him and that he’s a fool for being so slavishly dedicated to the company. This rebuke feels like incredible heresy, and Jim Moore can hardly believe someone would voice such opinions. But, maybe she’s right. In any event, she quits the job and says it’s not worth it. This book fits into my broader literary universe by looking at the flip side of the calamity that befalls my characters; showcasing how someone can dedicate themselves completely to a job in search of middle-class security but still miss out.

“But still miss out.” You could have focused on any number of things that Jim Moore has missed out on, but the inability to make connections and isolation seems to be a going concern with this work and other books of yours going back to your debut, Beautiful Piece. What is it about isolation that speaks to you as an author and what do you believe is the impact of ongoing isolation?

This question really gets to the crux of my work and to the mystery of it. You’ll remember that the original title of my first novel was, Alone in the Heat Alone. I remember when I was writing my book, The Rumphulus, which is a novel about men who have been abandoned by society and banished to the wilderness, that I believed I was writing a book that dealt so obsessively with social isolation that it might function as wisdom literature for men locked up in solitary confinement. I hoped that anyone suffering from social isolation might find consolation in The Rumphulus and really from all of my work. One of the stories that speaks to me most from the Gospels is the story of Jesus suffering the most terrible plight of abandonment and lonesomeness in the Garden of Gethsemane where Jesus feels abandoned by God. In some ways, I think all of my books and stories are a variation on this story of Jesus. The mystery to me is why is this the story I keep telling? Why are all of my story-telling energies drawn to this black-hole, abandonment by God, which always threatens to swallow my books up? And to be honest, I don’t know. Maybe it has something to do with trying to find the light, as my characters do hanging out in the bar in Ninety-Nine Bottles. For them nothing is more beautiful and sustaining than “the long-varnished top of this old and dented bar scuffed by glass and elbow and the light shimmering off its surface.” Once they establish this basic act of witness, anything seems possible.

I suppose all writers, if not all humans, are seeking some kind of light in their life and on their journey. It feels to me that your journey has been one of engaging in this search through the act of writing itself, and I wonder if you know why it’s been writing versus some other medium, what you’ve learned and what seems possible to you?

Ben, I think that you’re right: that my journey in life has been through the act of writing and I don’t know why that is. I’ve never followed the path of other writers. I’ve never participated in writing programs. I’ve never workshopped a story. I don’t have an agent. I don’t really engage with the whole writer community. My writing-vector is very inward and hermetic. Writing feels like an incredibly private act. I don’t follow standard models of storytelling. Repetition drones through my work like incantatory speech. In some of the pieces that I’ve written for Ninety-Nine Bottles and in some works that I’m working on now, I feature artists who are obsessed with making their art, but their art seems so incredibly private to the artist that the artist refuses to make it public. The tattoo that is incredibly private and not meant for public display is a recurring motif in my work. I’m currently writing a piece about a piano player who is insulted by people who tell him he should perform. That’s not what this is about, performance! he says. In fact, Memorandum from the Iowa Appreciation Society is also the story of a man, Jim Moore, who despite the prodding of people who care about him, refuses to open up and tell his story. No one knows, for instance, about the woodsman that visits Jim Moore in his imagination, and he’s not going to tell anyone either. I think there is something in this circular-hermetic state of the imagination talking to itself for its own purposes that generates my work. Nevertheless, I’m incredibly lucky to have found so many wonderful publishers who have supported my work along the way and who have helped me to find a readership for my work.

Ben, I think that you’re right: that my journey in life has been through the act of writing and I don’t know why that is. I’ve never followed the path of other writers. I’ve never participated in writing programs. I’ve never workshopped a story. I don’t have an agent. I don’t really engage with the whole writer community. My writing-vector is very inward and hermetic. Writing feels like an incredibly private act. I don’t follow standard models of storytelling. Repetition drones through my work like incantatory speech. In some of the pieces that I’ve written for Ninety-Nine Bottles and in some works that I’m working on now, I feature artists who are obsessed with making their art, but their art seems so incredibly private to the artist that the artist refuses to make it public. The tattoo that is incredibly private and not meant for public display is a recurring motif in my work. I’m currently writing a piece about a piano player who is insulted by people who tell him he should perform. That’s not what this is about, performance! he says. In fact, Memorandum from the Iowa Appreciation Society is also the story of a man, Jim Moore, who despite the prodding of people who care about him, refuses to open up and tell his story. No one knows, for instance, about the woodsman that visits Jim Moore in his imagination, and he’s not going to tell anyone either. I think there is something in this circular-hermetic state of the imagination talking to itself for its own purposes that generates my work. Nevertheless, I’m incredibly lucky to have found so many wonderful publishers who have supported my work along the way and who have helped me to find a readership for my work.

Let’s take one more beat on this last response. You are an author who states “I feature artists who are obsessed with making their art, but their art seems so incredibly private to the artist that the artist refuses to make it public,” and whose most recent protagonist will not tell people his story, and yet you have sought to be a published author who has in turn connected with “many wonderful publishers” to share your work with the world. This all feels gloriously paradoxical to me, do you agree?

Yes, Ben. I think that you have captured the whole strange conundrum of an essentially social person (myself) writing about characters who for one reason or another exhibit antisocial behavior. But the other thing that I want to say, and this goes back to something we were talking about in question six, and that is this: if we are trying to understand the other-side of the Horatio Alger story, in other words, if we want to know are there other ways to live a rewarding life than pursuit of the stringent demands placed upon us to be “a success,” then what might those rewards be? And I think that what the pattern of my work, which my publishers have helped me make public, seems to allude to is that the ability to bear witness to the actuality of the world, and to let the imagination speak for itself—these things seem to be their own prize that anyone can capture for themselves whether they are a success or not in the traditional sense.

Slightly changing gears, as we talk about all this, you also bring a unique perspective to the discussion, you work in the publishing industry, and so given your success, what’s your take on state of publishing these days and what do you suggest the authors reading this interview think about as they write and pitch their work?

My core recommendation gets back to this idea that the writer is most free as an artist when they don’t fret about the marketplace but rather when their own imagination becomes their primary source of interest and fascination. It gets to this concept that the writer can find their subject by carefully listening to their own imagination talking to itself for its own purposes. When I write, I write very close to the place where I dream. Once a writer has written their singular work, and if it is indeed singular, and if it works as a work in all of its aspects then they should be able to find a publisher and an audience for their work.

“I write very close to the place where I dream.” Love that and that may be as good a place as any to finish this dialogue. Before we do, is there anything I didn’t cover or you want to be sure to share? Also, please let us know where to find you. All that and thank you, I really enjoyed this.

Thank you so much for this great conversation, Ben. As always, you find the exact right note on which to end. The best place for anyone to find me is in my books, all of which are available on Amazon and in many local bookstores and libraries.

Get Memorandum From... at Bookshop, Amazon, or directly from University of Iowa Press

About the author

Ben Tanzer is an Emmy-award winning coach, creative strategist, podcaster, writer, teacher and social worker who has been helping nonprofits, publishers, authors, small business and career changers tell their stories for 20 plus years. He is the author of the soon to be re-released short story collection Upstate and several award-winning books, including the science fiction novel Orphans and the essay collections Lost in Space: A Father's Journey There and Back Again and Be Cool - a memoir (sort of). He is also a lover of all things book, taco, Gin and street art.