Photo by Karen Maria Photography, via author's website

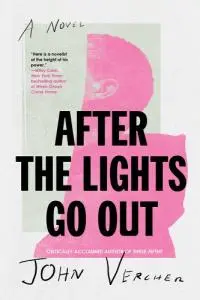

I've followed John Vercher's career from the start. After reading his debut, Three-Fifths, I knew he'd go places because he could do action and violence while also showing a knack for great writing. With the release of After the Lights Go Out, Vercher has delivered on every single expectation I had for his sophomore effort, and he did so with flair. A novel that takes place in the world of mixed martial arts, After the Lights Go Out is an impressive narrative that deals with a broken family, racial tension, dementia, and the world of fighting. To celebrate its release, I asked Vercher a few questions about the book and his writing. Here's what he had to say.

I've read both of your novels—'Three-Fifths' and now 'After the Lights Go Out'—and race is very present in both. However, it's not necessarily a racial discussion; more like you're presenting the reality of Black lives in different contexts. How do you approach race, which is now a touchy subject, when writing?

I think it’s safe to say race has always been a touchy subject, but I get your point. I read a meme once that went something like, “No one ever had their opinion changed by a social media post.” My goal has been to approach discussions of race from a place of empathy in that—and forgive the cliché—I want readers to take a walk in another person’s shoes. I want them to experience what a life unlike their own might be like by creating a character they care about. In that way, any narrative I want to tell regarding race isn’t delivered through proselytizing and finger wagging, which can be detrimental to achieving discourse. I have to believe understanding can be achieved through empathy. It might be lofty, but it’s what I’m aiming for.

One of the best things about 'After the Lights Go Out' is how authentic it feels in terms of everything that had to do with MMA training and fighting. From throwing hands to getting hit to cutting weight to waking up with pain from years of getting hit, you nail every aspect of it. How much of that came from research and how much came from your own experiences as a martial artist and someone who has stepped inside the cage?

My research was my experience and my experience was my research. Even though I competed as an amateur for a short period in kickboxing, MMA, and jiu jitsu, I always want to be perfectly clear—I was a tourist. I in no way had at stake what the men and women who compete in these sports did, either as professionals or as amateurs on the path to becoming pros. I trained and competed to challenge myself and was fortunate to have the chance to do so. It was because of that fact that I took my own training and competing so seriously. I cut weight for fights and tournaments and had the aches and pains and bruises the morning after hard sparring sessions. Because these athletes sacrifice so much both mentally and physically, I knew that if I was going to write about the sport, I had to get the details right. I had to honor that sacrifice with authenticity. I’m hoping I delivered.

I'm all about mixing genres, and you do that here. This has touches of crime and a lot of violence, but at its core, this is literary fiction about grief, anger, loss, and facing mental health issues. Did that mix come about naturally, or were you purposefully trying to show it can all dance together beautifully?

When I showed up to the first day of my MFA program, I honestly didn’t know shit about genre. All I knew was I loved stories that moved me, filled with flawed characters who were just trying to make the best of some bad circumstances, either of their own making or someone else’s. So no, there was no purposefulness to mixing those elements together, in the sense that I didn’t say I needed to sprinkle in a little of this or a little of that. I felt that all the issues present were necessary to tell Xavier’s story in a meaningful way that felt genuine and compelling to the reader.

Xavier, your main character, is likeable and not that great, violent and also hurting, easy to connect with and very unreliable. How did you approach character development when it came to Xavier?

The best writing advice I’ve ever gotten is write the book you want to read, and what I love to read are books with flawed main characters at their center. I actually like feeling conflicted about whether or not I want them to win in the end. Characters that are one-note are disinteresting. If they’re pure evil, they’re boring. Same if they’re characters that can do wrong. Not only are they boring, but they’re not real. They’re flat and unbelievable, and as such, I’m not invested in their outcomes. Xavier has so much at stake from the very beginning that if I didn’t make him multi-dimensional, those stakes wouldn’t be sustainable throughout the book, and no one would care about how he saw his way through.

One of the big demons in this novel is dementia. What made you add that to the mix and what was the research like? How important was it to you to show different stages and points of view when it came to this condition?

As a former physical therapist, I didn’t feel I could responsibly tell a story about combat sports without addressing the effects of post-concussion syndrome and its parallels to age-related dementia. I’ve treated a number of amateur athletes post-concussion, as well as those with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. It is equally fascinating and terrifying to see what happens when the mind begins to betray itself. We tend to view these things from a wide angle lens which allows us some safe distance from them because they feel almost impossible to deal with so, as with issues of race, it was important for me to convey them in a way they could be understood through empathy with the characters. Dementia, whether from CTE or Alzheimer’s, not only affects those who suffer with it, but those who care for them. It can be arduous and emotionally draining, and the dignity of both caregiver and care receiver can suffer and I wanted to bring light to that.

Everyone in this novel is profoundly flawed and, in some cases, not looking to do better. There's something awesome in that honesty. Also, Xavier talks to himself a lot about accepting who he is, violence and all. Why did it matter to you to show that honesty, to show that most of us aren't that great and we all have a dark side?

Everyone in this novel is profoundly flawed and, in some cases, not looking to do better. There's something awesome in that honesty. Also, Xavier talks to himself a lot about accepting who he is, violence and all. Why did it matter to you to show that honesty, to show that most of us aren't that great and we all have a dark side?

At the risk of sounding cynical—that’s kind of life, isn’t it? And my favorite books to read are those that reflect real life. Realism and authenticity on the page are important to me as a reader, so they are important to me as a writer. If a character’s behavior feels out of step with that, it pulls me out of the narrative, and that’s the last thing I want a reader to experience.

I'm not going to ask you about the dog in the novel, but I will ask you about dogs in fiction in general: Kill the dog, yes or no? Why?

Ha! So you’re not going to ask me about the dog, but you’re going to ask me about the dog? I see you. Would it be too Fozzy Bear of me to say I don’t have a dog in this fight? Honestly, I love dogs, I’ve had them all my adult life, I don’t think I’ll ever be over my first one dying. That said—it’s fiction. This might be an unpopular answer, but in my opinion, if it’s not gratuitous and it serves the story, then I’m okay with it. We read fiction to be taken on a journey, and not always a pleasant one. Of course I’m always going to hope nothing happens to a dog in a story—but I hope that for the people as well.

A lot of people think having a good friend who is a person of color or being in a relationship with a person of color immediately means that an individual can't be racist. This narrative destroys that idea. What did you want to accomplish by eviscerating that concept?

I wanted readers to step back and examine their allyship. To ask themselves what it really means to be an ally in the struggle we face. To understand that it’s possible to say you stand for something, to enter into a relationship with someone, and still be wholly unaware of your own biases and prejudices, to even convince yourself they don’t exist because you have that friend or that spouse. It’s an important discussion, one we don’t have enough and in a meaningful way, and one that I genuinely believe can help move us toward a better place.

You started out with an indie press and quickly moved on to a bigger one. What can you tell writers trying to do the same?

As selfish as it might sound, write for you and no one else. Don’t write what you think you’re supposed to write—write what you want to write. You will find your audience. And when you do? Know your worth and don’t forget it.

I hate this question, but love it whenever I find myself actually caring about the answer, so...what are you working on now?

Another book. That’s all you get.

Get After the Lights Go Out at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, journalist, and book reviewer living in Austin, TX. He’s the author of ZERO SAINTS, HUNGRY DARKNESS, and GUTMOUTH. His reviews have appeared in Electric Literature, The Rumpus, 3AM Magazine, Marginalia, The Collagist, Heavy Feather Review, Crimespree, Out of the Gutter, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, HorrorTalk, Verbicide, and many other print and online venues. Y