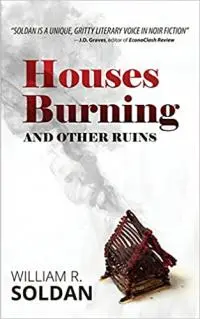

Photo courtesy of the author

Much like a motorcyclist will effortlessly weave through standstill traffic, my favorite writers tend to be ones who curve between staunch genres to find their unique voice. Since his debut short story collection, In Just The Right Light (Unsolicited Press, 2019), William R. Soldan has propelled himself steadily through the exhaust, wielding a more contemplative, "lived in" literary-style than others tend to take with crime and noir. A two-time Pushcart nominee, Soldan continued showing his range with Lost in the Furrows (2020, Cowboy Jamboree), and his debut poetry collection So Fast, So Close (Close to the Bone, 2020). His latest collection, Houses Burning and Other Ruins (Shotgun Honey, 2021), shows his distinctions opening up wider, further honing his grief-strciken storytelling where the bleak American experience occasionally collides with glimmers of righteous humanity.

Your work is often tagged as “Grit Lit.” So long as you feel that’s accurate, how would you describe that in your own words?

I think it’s good label for it, though such categorizations are never at the forefront of my mind when writing a story. I’ve always written gritty stuff, since before I heard the term. Coming from a working-poor and working-class background as I do, the characters I write about tend to come from the same background. These types of characters—those on the lower rungs of society who know struggle intimately but are tough and resilient—are the sorts of characters that populate what most of us would call Grit Lit. If you googled the term, you’d get tons of similar descriptions about “hardscrabble” folks living “rough and tumble” lives, always facing some desperate situation or another. Lots of seedy locales, often in small towns or rural settings. Lots of hard living, poverty, violence or potential violence. Lots of people at rock bottom or falling fast.

What I like about the term is that it’s a bit broader than noir or crime, which are two other categories my works gets tossed into, even though I can count the number of straight up crime stories I’ve written on one hand. There’s always a criminal element in my stories, even the ones where crime isn’t the focus. Noir is a bit more expansive because a story can still be noir without being a crime story. I have a lot of those sorts of stories: bleak, tragic ones where maybe there’s some crime going on in the background or in the past, or maybe a crime is imminent but isn’t actually present in the story at all, or maybe there’s no crime but it seems as if at some point something criminal is gonna go down. I wouldn’t call these crime stories, but, as I’ve experienced, they could very likely get published in crime magazines or mystery magazines, because the tone of the work seems to appeal to those same sensibilities. Grit Lit, to me, encompasses both noir and crime, though it isn’t reliant on either one of them. I like that.

As someone who knows your work well, I feel Houses Burning and Other Ruins marks a slight departure for you. Since your debut collection In Just the Right Light, you’ve established a predominantly first-person literary fever dream style, that always addressed crime without necessarily being crime-fiction. With this new collection you've jacked the intensity up, and now it’s on a proper crime-fiction imprint (Shotgun Honey). Was this a conscious move?

Not really conscious, no. Though while compiling this collection I was aware that it was more crime heavy than my first two, so it’s a departure in that regard. But like my other books, there are several — at least half — stories in Houses Burning that fall into that more ambiguous Grit Lit/noir-without-being-crime category. Regardless, I’m thankful for that readership, because quite a few readers of these genres have really embraced my work, even the less genre specific stuff, which is most of it, honestly.

Not really conscious, no. Though while compiling this collection I was aware that it was more crime heavy than my first two, so it’s a departure in that regard. But like my other books, there are several — at least half — stories in Houses Burning that fall into that more ambiguous Grit Lit/noir-without-being-crime category. Regardless, I’m thankful for that readership, because quite a few readers of these genres have really embraced my work, even the less genre specific stuff, which is most of it, honestly.

Since there are more crime focused stories in it, the tropes of that genre probably are more obvious, and the intensity level is for sure higher at times because of it. None of that was conscious while writing, though, and probably only half-conscious while compiling. I just write the story I feel compelled to write at the time, and later I decide where it fits best.

Several of the stories in Houses Burning were actually written before my first book was published, but these stories, most of them, are a bit more urban in setting, so I never even considered putting them in my first book, which is predominantly set in one fictional rural town. One day I realized I had enough for a collection that could potentially get picked up by a noir/crime imprint. I’d known about Shotgun Honey for a while, had been reading the online mag and had even published a flash piece with them, so I rolled the dice and sent them the first story of the collection. They requested a full manuscript, and I was happy to oblige. Back then, though, the new book contained a couple stories that ended up in my first book, so after they expressed interest in publishing it, I had to remove those stories and replace them. Luckily, I’d since written more stories that were a better fit for the book than the original ones anyway.

Your work feels extremely lived in, unmistakably written by someone who experienced first-hand a lot of the informed darkness in your stories. Was there a specific point where you were able to scale back that chaos in your life so you could focus on writing, or were you writing through it all?

I started partying at a pretty young age. Thirteen was when I was consistently getting high and discovering the joys and thrills of chemicals. I was the kid that would try anything, and I tried a lot, and I’m lucky I’m still here. But that was just the high school years. In my early twenties I lost what little trepidation I had about needles and heroin, and that, along with just about anything else that was on the table, became my undoing. During most of that time, I wrote song lyrics and poetry, but nothing worth revisiting. And when I was at my worst, there was no writing at all. The desire was there, and I’d periodically get ambitious—usually while spun on crystal or something—and I’d be “productive,” which really just meant that I only slept like once a week and had a lot of partially-finished projects all over the place. Heroin on the other hand, I could never accomplish a damn thing on that shit. I’d come up reading the Beats and junkie writers like Burroughs and Carroll and when I was finally in the thick of that lifestyle myself, I was all like, How the fuck did these guys write books on this shit? All I could accomplish was nodding out and burning holes in my clothes, because habits grow unruly, and life becomes all about making sure you get what you need to not feel sick. And that shit becomes a full-time gig. No holidays or weekends off. No benefits other than temporary reprieves from wishing you were dead. Not such happy days, those.

But I was able to beat it. I got clean and if I hadn’t, I never would have written one book, much less multiple books. I would have continued to romanticize the kind of life that was killing me, and eventually I would have died in some shitty apartment or in my car at a truck stop or in a Wendy’s restroom. But then I got arrested. Prison is really the one to blame for me still being alive. It was there I was able be away from substances, to get my head clear and realize I wasn’t only hurting myself when I was out there running, which I’d always known, but us addicts love to rationalize and make excuses for ourselves, act like our heinous actions only affect us. While there, I began writing again, filled notebooks, but I still wasn’t writing fiction, only poems and songs.

By the time I started writing fiction, I’d been fortunate enough to be separated from my old lifestyle for a few years, to be not only motivated but also capable of putting in the work. Just as none of my books could exist without the experiences from that part of my life, they also couldn’t exist if I had continued on that path. I’m glad things worked out the way they did. As bleak as I can be, I’d much rather be here than not.

On the subject of authenticity, do you think an author’s work is better when they’ve lived the material they write about, or is an author’s imagination the true test of their talent? I’ve come across a number of crime-fiction writers who appear as if they’ve never even been in a fight before, some of which have incredible imaginations, but seem more informed by thriller movies or even superhero tropes as springboards.

I think it’s ideal to have equal experience and imagination. But an inexperienced writer with a wicked imagination will always outdo the experienced writer with no imagination. At best, what experience with lack of imagination yields is something that reads like a memoir chockfull of the boring parts. If writing from your life experience, you still need to know what to do with all that raw material. That’s where imagination comes in. Of course, you also need discipline, to develop technique and style and voice and everything else, because a writer can be highly imaginative and still not write a good story.

And when I say experience, I don’t mean you have to have experienced everything your characters are experiencing, but that you mine your personal history for the details that make the story feel authentic. I haven’t experienced every single thing my characters have. I’ve never held up a convenience store. I’ve never shot anyone. I’ve never been to war. But I know people who have, and I come from the same world as a lot of these folks, so I can imagine the circumstances that would lead one to do such things.

Because I’m sitting here today, relatively healthy, with a family and enough distance from certain experiences, I can say I’m thankful for the days when my life was a disaster, because my work wouldn’t be what it is, and I’m overall happy with my work and its trajectory. Am I saying every writer of crime fiction should go out and commit some crimes? Am I saying that every writer of Grit Lit or noir or dirty realism should rush out and pick up a dope habit and get in a bar fight? Of course not. But if you happen to have experienced those things, or you’re close with folks who have, I’d say you have an edge over the tourists. I’m not knocking suburbanites who write crime thrillers or whatever. More power to them. Many are probably pretty damn convincing in their portrayals of addicts and criminals. But when real lived experience informs the writing, I think it definitely shows. Readers can sense what’s sincere and what isn’t. I can only assume that’s true, because most of what’s been described as authentic and sincere about my own work is directly related, in some way, to what I’ve been through and where I’ve been. My experience is tame compared to some, outrageous compared to others. But it’s mine, and so far it’s served me well when writing about the things I do.

You write a lot about Ohio. What is it about the state that captures your imagination, besides it being home? I know for many it’s a bummer conservative state — but it’s an important hub of blue-collar pride while also being consistently fertile ground for artistic iconoclasts. I personally see it as a sort of a ground zero for the American Experience, for better or worse.

I’m originally from Milwaukee, but in the late 80s my mom and I moved to Youngstown, where I grew up and, with the exception of some brief stints in other cities and states, have lived all my life. As a teenager, I hated it, even though I had some great times here then. I shared with a lot of other kids the strong urge to escape my hometown. I don’t think there’s a kid alive who doesn’t have an ambivalent or downright contentious relationship with where they’re from. It’s in our nature to want to break free. And I did, more than once. Sometimes I returned out of necessity, because I needed to go somewhere and had nowhere else to go. Other times I returned because I was homesick or wanted to be closer to what little family I had. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to love it here. I’ve got a sense of pride being from here that I never had when I was younger.

I’m originally from Milwaukee, but in the late 80s my mom and I moved to Youngstown, where I grew up and, with the exception of some brief stints in other cities and states, have lived all my life. As a teenager, I hated it, even though I had some great times here then. I shared with a lot of other kids the strong urge to escape my hometown. I don’t think there’s a kid alive who doesn’t have an ambivalent or downright contentious relationship with where they’re from. It’s in our nature to want to break free. And I did, more than once. Sometimes I returned out of necessity, because I needed to go somewhere and had nowhere else to go. Other times I returned because I was homesick or wanted to be closer to what little family I had. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to love it here. I’ve got a sense of pride being from here that I never had when I was younger.

When I began taking writing seriously, I was actually writing horror stories. Some of them were set here, but I hadn’t really made a conscious decision to set most of my work in Ohio. That happened after I discovered writers like Donald Ray Pollock, who’s also from Ohio, and other midwestern writers whose work I devoured when I found it, folks like Bonnie Jo Campbell and Daniel Woodrell and Frank Bill, to name a few. Their work blew my mind, not only because they’re brilliant writers, but because I connected to their world so much because it was my world, a place that was in my bones. I knew their characters because I’d grown up with some version of them all my life.

That was a real revelation for me as a writer. They were the kinds of stories I wanted to write, even though I hadn’t known it until then. I hadn’t been writing fiction for that long at that point, but when I realized I had a deep well of experience that I hadn’t really been tapping into, I felt exhilarated. That’s around the time I began working on the stories that ended up being my first collection. I was mostly mining a period of my life when I lived in a series of small rural towns much like the fictional one in the book. That period of my life was still very vivid in my mind, having been another fairly unstable period, especially for a kid. And each time I started a new story, I set it there. I discovered I loved writing about this place, because I know it well, and I feel a sense of innate authority over this geography. It’s an economically impoverished area. Because of its blight and struggle, it’s a great place to set crime fiction/noir/Grit Lit. The landscape itself almost demands it, as does its history. Deindustrialization, rampant unemployment, and crime. One leads into the other into the other. That’s a big part of our story here. Most folks who know the name Youngstown but aren’t from here, associate it with one or more of three things: Abandoned steel mills, the mafia, and a high murder rate. Maybe the Springsteen song. To try and write about the folks who haven’t struggled in this area, or who aren’t still struggling, would be to write about a tiny portion of the population that’s fairly alien to me. I’ll always worry about money, about what could go wrong. I experienced too much of that as a child to ever feel truly comfortable, even when I’m doing better than I ever have been.

Writing stories that take place where I live has the added benefit of access. I am in the middle of it. I might have to look up stuff on the internet once in a while about local things, but if I need to get a visual to help me establish a scene or something, I need only take a walk or drive around.

I also just like the idea of showing this place some love. We get talked down about a lot, our name only trotted out on the campaign trail, used as a soundbite in political rhetoric about the economy. After elections are over, though, we fade back into obscurity, a place that once had so much to offer but is now just a ghost that gets conjured every few years. I think we deserve to have stories about us and where we’re from. Few people pay this part of the country any mind at all, and fewer still are writing about it. I’d like to contribute to changing that in my own small way.

Give us two books — one book that altered you when you were young, and one that altered you more recently.

The Boxcar Children by Gertrude Chandler Warner. My second grade teacher—this awful, ogre of a woman—read it to us, and I loved it. It eventually became a series, where the siblings go off and solve mysteries and stuff sorta like the Hardy Boys, but that first book was just about these three orphans who lived in an old boxcar, struggling to survive and taking care of each other. I don’t remember the exact storyline, but I still remember how much that book impacted me as a poor kid who’d recently been separated from my own siblings. I mean, it’s the type of thing I’d probably write if I wrote books for children. The premise alone is Grit Lit as all hell, if you ask me.

The Residue Years by Mitchell S. Jackson. No book has made me want to up my line level game more than this one. Jackson is one of my favorite, if not my favorite, prose stylist. His lines are the kind that’ll make you jealous in that good way — that thrilling way that makes you look at each sentence you put down as something isolated that can be magnificent. I strive to write the best sentences I can, and I think I write some pretty good ones on occasion, but discovering his work really made me want to try harder, to be better. It’s my hope that everyone out there who cares about the micro level construction of their lines will read his work and see that a sentence can be a powerful thing if we treat it as such.

What’s some hard-earned advice you’d give to a young person just starting to write?

I’m not big on giving advice. Hell, I’m still figuring this shit out as I go. But I I’ll suggest that a young writer be diligent. Just put in the work and don’t get so focused on seeing yourself in print that you jump on the first train that rolls through. Lots of people might offer to publish you, but a lot fewer are going to really invest in you and your work. Have a sense of urgency about what you do, it helps keep the fire burning, but learn patience, too. The desire for instant gratification is strong in all of us. Listen to your instincts, especially if they run counter to this desire.

Get Houses Burning and Other Ruins at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.