Photo courtesy of Kristin Garth

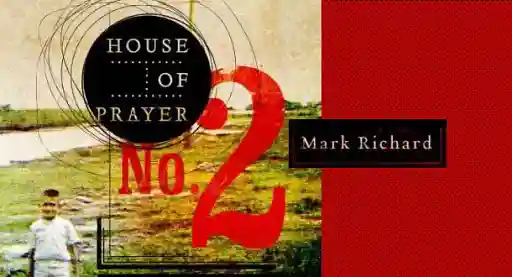

Pensacola, Florida author Kristin Garth is deceptively innocent; in her signature Catholic school-girl outfit, she's a sneering key holder of Pandora's box, where her illicit adventures are written. Like eloquent and elaborate notes passed in class to make us squirm, she'll eventually repossess every secret to throw into a playground fire, after she's gathered our expectations as kindling. Her new novel The Meadow (a companion piece to a poetry collection by the same name), is her most revealing and complex offering yet—a breathy chronicle of life as a submissive that's a defiant statement in our marketable age of mainstream female empowerment.

Garth is also the editor of Pink Plastic House, a lit journal constructed of a dollhouse where writers occupy themed rooms with furniture and accessories.

Scarlet, the MC, returns to a happy place she calls the Meadow when her innermost desires are fulfilled, or at times, threatened. Can you explain The Meadow in your own words? From the cover it almost looks like a children’s book, but the content is anything but. How does innocence inform such an adult novel?

To understand The Meadow, which in a different vernacular could be described as a sub space (a euphoric mental state of a submissive in a scene), I have to first assert that this is a story of masochism and submission which is uniquely Scarlet’s — though it is based on my own experiences. I do not have the authority or the desire to speak about submissives and masochists, why they crave the things they do or behave as they do. I use Scarlet’s biography, which I acknowledge is brutal and not typical of a submissive or a masochist, because it’s a familiar story to me.

I went to “the meadow” in my mind first in the context of abuse as a child. It was a place I disappeared into instead of being where I was. Only a few years ago, I was reading an article about masochism and it gave the best explanation for what I think I was doing at the time. It referenced a switch inside some people that gets flipped, when they are young, for a number of reasons including abuse, but also things like chronic pain or necessary medical interventions. That as part of an individual’s survival they learn to take an unavoidable painful experience and decide it is not painful or, in fact, that it is pleasurable to make it psychologically feasible to repeat. The article didn’t assert this was the case for every masochist but some — and I knew when I read it that I was one of those.

For me, the switch flipping happened during spanking which, in my childhood, was frequent and over-the-top angry and accompanied other abuse. I would lose my voice from my screaming, crying, and begging for it to stop and these sessions would go on longer and longer. It’s sad when, as a child, you realize someone relishes your pain, but I did realize this and soon thought: what if I pretended to like it? My upbringing was puritanical and something in me already knew that this would stop things — pleasure. So I made my mind a meadow as Scarlet says in the book and I made myself pretend to like it. Would not cry and actually begged for more. It sounds easy but I assure you it wasn’t. But it did make it the spanking stop.

For me, the switch flipping happened during spanking which, in my childhood, was frequent and over-the-top angry and accompanied other abuse. I would lose my voice from my screaming, crying, and begging for it to stop and these sessions would go on longer and longer. It’s sad when, as a child, you realize someone relishes your pain, but I did realize this and soon thought: what if I pretended to like it? My upbringing was puritanical and something in me already knew that this would stop things — pleasure. So I made my mind a meadow as Scarlet says in the book and I made myself pretend to like it. Would not cry and actually begged for more. It sounds easy but I assure you it wasn’t. But it did make it the spanking stop.

I felt powerful for being able to endure something and take control. My sexuality is shaped by all of these experiences. I know it’s not that way for many other abuse survivors, but I wanted to feel sensations I felt outside of the context of the abuse. I sought that out. The Meadow existed inside me, and I wanted to go back to it in a way I chose, with people I chose.

The cover of The Meadow is beautifully innocent. Jeremy Gaulke, the publisher of APEP, designed it when I did the poetry collection of the same name with his press before the novel with Alien Buddha. We didn’t use this iteration for the poetry collection and I had already written most of the novel by this time, so I asked him if I ever did publish the novel if I could use this cover for that. For a person who was raised feeling shame for the slightest expression of sexuality and then made to feel freakish by terrible people who knew my dark desires, it felt so affirming and positive to see such a delicate representation of my id. It’s taken me a long time to embrace my complexities as beautiful — that I can be delicate and crave rough and that is natural. I think that is one of the messages of The Meadow, that we all are innocent and depraved. And even on the cover, hidden amidst those flowers and tall grass you can see the top of a bondage cross peering out to you almost like a predator in a serene bush. Life is complex.

Let’s talk control and submission. My ex-girlfriend from twenty years ago was a dominatrix who worked in a Los Angeles dungeon where most of her customers were male cops and CEOs who wanted to be humiliated and beaten, most of whom never wanted any kind of sexual exchange – just a focused experience of mental and physical pain. And she loved being a woman in control of dishing it out, because these men were often trying to find atonement for the physical, mental, and verbal abuse they put others through daily, so she felt like the ultimate avenging angel. Is there an empowerment of a woman being submissive like Scarlet in The Meadow?

This question is so good and one I grapple with people’s misunderstanding of every day. Scarlet, like myself, is bisexual and submits to both men and women in The Meadow, but her two primary BDSM relationships in the book are with male dominants. To say she has daddy issues is an understatement, and we even see why. But it’s not a politically correct or traditionally feminist image of sexuality.

What is reductive about this view is choice. It is always empowering for a woman to go after what she wants. I went to therapy during the time of my life that is mirrored in The Meadow. The therapist I went to undid a lot of the damage that existed in my head because of my puritanical upbringing, how I viewed my sexual self. Before therapy, I felt very broken and shameful about the things I was doing. I made bad choices too, because I saw my kinky sexuality as inherently self destructive, based on the monologue of misogyny that accompanied my maturation. Also, my path in BDSM was not without growth and maturity; I was making mistakes. Submission was something I wasn’t always taking appropriate control of in ways I should.

This doctor taught me that my sexuality was a unique gift and that self destructive part came from giving that gift to the wrong partners. He built up my self esteem and made me feel in control with whom I could be out of control. In the novel, Scarlet never sees a therapist, but the book ends in a way that I think mirrors that kind of internal work I did with my therapist.

I often wished I was a female dominant like your ex-girlfriend — how I would be embraced in our politically correct world. The closest I came to that was striping where I feel I was a financial sadist to many men. Doing that job in pigtails and plaid skirts, a uniform of innocence which also felt like a uniform of my abuse, I’ll cop to feeling some glee at times.

Obviously not all will adhere to the exact same path, but is there a common trajectory how someone becomes a dom or a sub? Is it ever a conscious decision, or is it more due to outside influence, as if trauma makes up your mind for you?

I don’t think there is a common trajectory at all. When I was active in the scene, I encountered women like the character of Evelyn in The Meadow who were accomplished and powerful in their fields but were sexually dominant. I also met powerful men like this or some like your ex-girlfriend’s clientele who had lots of control and wanted to lose it in their sexual lives. I never met, in my time, a girl doing the things I was doing for the exact reasons I was. That was one of my main insecurities with writing both versions of The Meadow. I didn’t want them to be taken as some kind of authoritative text on the subject. It is a story of submission and masochism — it’s not meant to define anyone else’s motivations and experience. Scarlet makes lots of mistakes and evolves, and that’s all we can ask of anyone.

Format wise, the novel The Meadow came out after the poetry collection The Meadow, which is quoted in each chapter of the novel. Did you plan on the novel when you were writing the collection, or was it an afterthought?

It’s funny you ask that question because I know for a fact that most people assume I wrote the novel after the poetry collection. It’s understandable because it was published after the poetry collection. Reading an excerpt of the novel recently, the host referred to the book as a novelization of the poetry book. In fact, the poetry book is the novel poeticized.

It’s funny you ask that question because I know for a fact that most people assume I wrote the novel after the poetry collection. It’s understandable because it was published after the poetry collection. Reading an excerpt of the novel recently, the host referred to the book as a novelization of the poetry book. In fact, the poetry book is the novel poeticized.

Not knowing how to begin my journey into publishing, I happened upon Scribophile, which is a critiquing site for writers. I thought being part of a community would make me accountable in the formation of a new habit, which was writing every day. I worked on the beginnings of two novels there that I’ve since published — The Avalon Hayes Mysteries and The Meadow. On the site I was more known for the latter due to its salacious subject matter. The book had its fans and detractors — though they never saw the completed novel. You could publish a chapter at a time for critique. A version of three-fourths of that book lived on that site before I got distracted writing sonnets and being directed to a publisher who was interested in those.

Once I came to poetry Twitter, I really took off with publishing my Shakespearean sonnets in a lot of venues and a lot of poetry opportunities came my way. When I first spoke to APEP about The Meadow, the publisher was intrigued with the story but had a hard limit on the amount of pages he could publish as his publishing was all done in-house. I had by this point written sonnets that encapsulated stories from the novel. I arranged what I had into a manuscript and, with the publisher’s input and notes, I wrote more to flesh out the story. You can read the poetry collection of The Meadow free online here.

There’s a line of dialogue that suggests Scarlet is not a typical submissive, when Alex says, “Scarlet, you’re not just submissive; you’re passive. You allow things to happen to you that you do not want…” Could you elaborate on this element of her awakening, and what the difference is between being submissive and passive?

A lot of my journey in masochism and submission was learning healthier ways to act out these behaviors. Though the context of BDSM provided a lot of healthier dynamics like contracts where permissible activities were discussed and defined beforehand, I still did things that I personally didn’t like or want to do with partners out of a desire to be accepted or to please. It’s in my nature, but not all parts of our nature are positive. For me, I had to learn the difference between being passive and being submissive.

When Alex says this to Scarlet in the book, it is because he knows that she has allowed unwanted things to happen. Scarlet is definitely aware she is not a swinger but she allows this to happen to her in the hopes that her gift of submission will be appreciated. It is not. Alex learns all this from Evelyn who introduces Scarlet to him, and while his character takes advantage of her passivity a bit, too, I do think he is afraid she will be really hurt by this one day. He speaks of this as she is about to become a stripper as a warning that the strip club is a place where one very much needs to assert boundaries and know thyself to stay true to them.

What do you see within literature as the main threat to its own evolution?

Fear is the enemy, and I feel that is true specifically in art. Fear has endless ways of stopping us. For twenty years, I didn’t publish or share my writing because of fear. Even when I did, it took me a long time to feel brave enough to publish The Meadow just because of the fear of certain reactions to it. After writing lots of poetry and being accepted for that, I felt fear when I put my first prose collected stories together, but I did it and feeling the love for that gave me renewed courage to put The Meadow into the world.

I think online so many artists are afraid of being themselves, saying what they think and desire. Whether you fear being unpopular or being canceled for your art, I think fear is antithetical to creation. For me, when I fear something now in writing, I try to find a way to do it even if it requires breaking it down to simpler steps. Never be afraid to be who you are and create the art that is authentically you. That’s always my goal.

Get The Meadow at Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.