Photo via author's Facebook

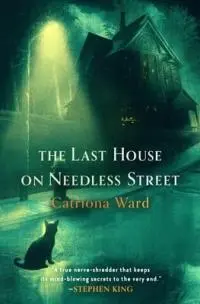

This last year has been an impressive one for horror author Catriona Ward. The Last House on Needless Street swept through the book world, garnering impressive reviews and stirring rumors that it might be headed to Hollywood sometime soon. In early March, her newest book, Sundial, was released to similar acclaim. I was delighted to spend some time talking to Ward about why she loves horror, the importance of a writing schedule, and why failure is a necessary skill for every writer to learn.

When did you start writing? And what drew you to horror, in particular?

I spent my early twenties as an incredibly unsuccessful actor. But I did catch the storytelling bug, and in my late twenties I started writing. Rather than having a novel that I honed my skills on and shoved in a drawer, I wrote and rewrote The Girl from Rawblood for seven years.

Horror has always appealed to me because it has a huge amount to say about all the things you’re not supposed to talk about. It has a particular quality to it, where the writer and the reader face their fears hand-in-hand. When I was growing up, we lived all over—the US, Kenya, Yemen, and Madagascar. So I learned stories are the best way to learn about yourself without direct interaction with people. When I started to feel different in my teen years, I had a lot of feelings I didn’t know how to deal with. I felt very drawn to horror, Gothic, and dark fiction because of how they helped explore those feelings.

As a genre, there can be a tendency to make it cartoony and campy, which makes it seem like it’s somehow not as serious as real literature. I get quite cross when I read a line in a review that says something like, “the writer transcends genre.” This happens quite often when writers who are considered more literary write something more genre. It makes it sound as if genre writing was a ditch to be climbed out of. Why must the genre be transcended? Surely, genre writing has as much validity as anything else. Especially when so much of writing happens off the stage. You don’t always realize what parts of yourself you’re using until you step back to see the connections you made on the page.

As a writer, when you write what you’re afraid of, you’re making yourself vulnerable to the reader. Each book is you showing your soft parts and asking the reader if they’re afraid of those things too. I’m a big believer in this mutual reciprocity becoming a great empathetic exercise. By bringing your fears out into the open, you’re showing something private that people don’t tend to talk about. I think that’s very powerful and makes people feel less alone. It’s a huge part of why I read and write that kind of fiction.

I also think there’s an inoculation element to horror, almost like if you sample what you might feel in a certain situation, then it doesn’t have as much power to hurt you. Horror has a narrative. It has a perpetrator and there’s a reason why the bad thing happens. There’s an element of feeling like you can prepare for the worst. It’s more organized than the arbitrariness of life and there’s a resolution to it, as well. I think sometimes we seek out the monster just to prove that we’re not the monster. And I think the people who are not the monsters are the ones who ask themselves questions like that.

Did you always know you wanted to write horror?

As I said, I was drawn to horror, but it took me some time to realize why. When I was about thirteen, I started waking up in the middle of the night with a hand on the small of my back, firmly pushing me out of bed. I remember feeling every individual finger where they were touching me. It was probably the most terrifying thing that’s ever happened to me, but instead of telling anyone, I just started sleeping on my sister’s floor for about four years.

Over time, it stopped, and I sort of shelved it and put it away. I remember reading The Monkey’s Paw by W.W. Jacobs when I was eighteen, and I got that feeling again. That fear, like someone wrapping a cold hand around your heart, and I thought, oh, this is where you put that feeling. The story felt like a cage to contain that abject terror that I remember feeling as a girl. It spoke really powerfully to me about the deep and profound nature of horror, and the relief it can bring. By my twenties, I knew those experiences were hypnagogic hallucinations, but at the time, as far as I was concerned, it was a ghost. I think that’s proof of how deep these experiences can go and how profoundly they can shape you. When I began writing, horror is what came out.

Writing can reflect your mental attitude towards the subject rather than being lifted out into storytelling. But at the same time, it has to be crystallized into something that isn’t just emotional vomit on the page. There are so many ways you can fall from the tightrope of narrative. You have to balance so many moving pieces, and if you get one tiny bit wrong, it can puncture all the other hard work you’ve done. But there is something cathartic about taking monsters and showing how they’re just expressions of ourselves.

What does your typical writing day look like?

I used to treat writing a bit like a séance, settling in late at night with a glass of wine and just waiting to be visited. But I don’t really have the luxury of that when it’s my job. Mornings have become my sacred writing times.

One thing I’ve discovered is that no two books want the same thing from me. Needless Street really wanted to be written on the move. So, I spent a lot of time on trains, and one time in France, I took my laptop into the forest to just sit and write. That actually ended up being very effective. Sometimes it’s really helpful to be somewhere different. A change of location can shake your brain loose of its habitual patterns. Writing already feels like you’re spending so much time staring at a screen. And if you can’t change at least the wallpaper behind it, it’s easy to get stuck.

When I sit down, I’m typically just reviewing what I did the day before. That’s a big part for me, because I always find no matter how inspired I felt yesterday, today it might be barely comprehensible. It’s often two steps back before I start with new words. I think reviewing helps embed you back into the narrative.

I always aim for 2,000 words a day, especially when I’m on a deadline and need to stay focused. Sometimes I succeed, sometimes I fail, but the rule is I have to sit down and try. Even if I end up staring at the screen for two hours, that’s better than nothing. Writing can be really hard, especially when tackling new ideas that are overwhelming. But I’d rather be ambitious and try things that feel dangerous to write, even if it doesn’t quite hit the mark, then just do the same old stuff over and over again.

Do you have a different approach when it comes to writing such varied characters?

I do quite a bit of research while writing. For one project, I listened to Ed Kemper’s confessions. You’d think there are a lot of different layers to psychopathy, but it’s actually very boring. All of the things you hook onto from the narrative, like empathy and all of the things inside the rich interiority of the human mind is completely absent. It’s like this big, dark, empty room. There’s nothing there.

Olivia from Needless Street was a challenge. She represented such a rare patch of comfort and light in the book, but I worked really hard to make sure she wasn’t sentimental or cute. Writing an animal narrator is hard enough, and a cat especially, because that has so many cozy overtones to it. But in the end, she did the thing cats do, where she strolled in and was there.

The trickiest part is making a character whole. With Ted in Needless Street, I had to do so many things with him at once. I didn’t want the reader to just loath or fear him, they had to feel his humanity, but in a very tight line of characterization. That was technically very hard. In Sundial, Callie was a tightrope balance in a different but similar way. I didn’t want to tread into cliché. In both, I wanted to keep their characters, their experiences, and the way they saw the world sharp and spiky, so that the reader is always surprised in that spurt of the unfamiliar.

I find the unreliable narrator such an intuitive way to write because it resembles how we live. We don’t have any knowledge, or an omniscient narrator telling us what to think when we walk into a room. We just have to deal with whatever we find, which means we’re wrong a lot. Because we all see things so differently, and we represent things differently to ourselves and others, it leads to misunderstandings. Even if the narrator isn’t unreliable, it can be hard to know what the truth is, so I use that in my writing. I’ve learned to lean into and use it as an intrinsic part of my process.

What book would you recommend to aspiring writers?

I always recommend Get in Trouble by Kelly Link. It’s a short story collection and it makes the real seem unreal. The stories are there in the real place, which is a construct, and it’s how she takes it to the absolute length and epitome of the concept. If you want to learn how to create stories that transport readers, that’s exactly what she does.

I always recommend Get in Trouble by Kelly Link. It’s a short story collection and it makes the real seem unreal. The stories are there in the real place, which is a construct, and it’s how she takes it to the absolute length and epitome of the concept. If you want to learn how to create stories that transport readers, that’s exactly what she does.

If you’re going to write difficult content, I recommend I’ll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara. It’s true crime, but the way she resuscitates and breathes life into what are essentially bad statistics, while finding a way to make the crimes and the people involved live and breathe, is a really good lesson for writers. It’s also an excellent lesson in not using shock value to tell your story. McNamara shows you how to connect through storytelling. There are probably semi-fictionalized parts because she can’t know everything, but the way she humanizes the crimes is a really good guide for how to make that work.

Do you have any advice you’d give to aspiring writers?

Read everything you can and keep writing. No one can do it for you, and the only way to get there is by failing and failing and failing. I think it’s good to put yourself in an environment where you have a writing peer group. Learning from other people’s writing is invaluable. You’re looking at the things they do well and the things they don’t do so well. You’re also having them look at your work.

I found it’s really useful to have someone say they don’t like your work. There’s something about it that’s very empowering. I understand this may not work for everyone, so you have to be the best judge of whether your self-confidence is robust enough to withstand that. But if you can, I think it disempowers the idea that being rejected or criticized can hurt you. Not all criticism is valid, and learning how to distinguish between what is and what isn’t useful becomes a valuable skill. If five people don’t understand a specific piece or scene, you learn to identify what may not be clear, but you’ll also learn about how to accept personal reading preferences. I did a Master’s in Creative Writing, but I don’t think that’s necessary. You can join a writer’s group or take local classes and achieve the same skills.

So, it’s a three-pronged approach. Read a lot, because authors are your best teachers. Find a group where you can learn from people who are at a similar stage as you. And keep writing.

You mentioned failing as a way to improve. Can you talk about that more?

I believe if you get everything you’ve dreamed of the first time out, you won’t have a solid grounding. And then, success can destroy you. Because there’s no one left to blame except for you, and that can really overwhelm people. If you haven’t learned how to deal with failure, it can make success difficult to deal with.

In terms of writing, the difficult second novel is a real thing. It’s not invented. All books are difficult in different ways, but the second novel in particular was brutal because it’s easy to think anyone can write a novel and find success once. It could just be the right book at the right time. But can you do it again? Because you have to be able to do it again to be a writer.

I was at an event with Joe Hill, and we were talking about the second novel, and it was such a relief when I heard that he felt the same way. It’s difficult and it’s not a cliché. The second novel sort of becomes the proving ground. But if you haven’t learned to fail, that fear can hold you back or slow you down. When you find your own path, you stop judging yourself by other people’s standards.

Do you have any other advice?

Sometimes a draft is your first draft—even if you’ve written it a few times. Your first draft is you telling yourself the story, and you may not do that right the first time. But then you can come back and add all the really good stuff in the second, third, however many more drafts, until you can tell someone else the story.

Get The Last House on Needless Street at Bookshop or Amazon

Get Sundial at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Jena Brown grew up playing make-believe in the Nevada desert, where her love for skeletons and harsh landscapes solidified. In addition to freelance writing, Jena blogs at www.jenabrownwrites.com. When she isn’t imagining deadly worlds, she and her husband keep busy being bossed around the Las Vegas desert by their two chihuahuas.