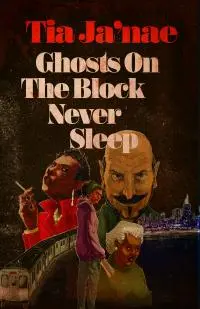

Author photo courtesy of Tia Ja'nae

Ghosts On The Block Never Sleep is the debut novel by hardcore Chicago author Tia Ja'nae (out in October on Uncle B. Publications). A singular tale of a female car-jacker who, because of her high-demand, acts as conduit to some of the most dangerous criminal elements in the city. It's a fast-talking, relentless yet introspective meditation on life/death, survival/deceit, and how far a woman's constitution for death can stretch before the reader begins to question her own sanity. It's a novel that is so vividly informed by time, place, politics, and culture that its immersion drops the floor from beneath you. The narrative doesn't arc, it straight descends — where street-level warfare sinks into psychic terror.

Your work primarily takes place in Chicago, where you hail from, and Ghosts on The Block Never Sleep is no exception – what is it about your city you're trying to spotlight, beyond the second nature element?

One of the reasons I write about Chicago so candidly is its past; its history isn’t exactly great when it comes to race relations, taxation, and political corruption. I’m sure you’ve heard the stories and seen Chicago as the nation’s punching bag for criminal behavior and a host of illegal mischief the last few years, especially when it comes to mayhem and murder. What’s always fascinated me is the knee jerk reaction to condemn it without understanding how it wound up becoming more infamous than Detroit – exploring the what, where, who, and how circumstances that brought Chicago to the state it exists in today.

Chicago just didn’t become the bastion of violence overnight – this has been something designed and orchestrated over the last fifty years. I’ve always hated the judgement by people not from there, because they don’t know or don’t care to examine the mitigating factors coming from City Hall and its policies since Daley that contributed to the problems that are over glorified in the media today. Most, if not all of my work explores how the racism, segregation, discrimination, and political corruption contributed to the heightened level of violence, especially when it comes to the city’s bad policies that have taxed most viable employers out, forced black people out, pitted races against each other, etc. Go all the way back to Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin In The Sun. The same issues she highlighted in 1959 Chicago are still prevalent in today’s Chicago, if not worse. A lot of my work is to just open up a discussion where people understand that Chicago is what it is because politicians created and profited from it being a survival of the fittest. The people there are just like everybody else, some just are doing whatever they feel they have to do to survive, and sometimes that can lead them down a road they never thought they’d go, or get to a point of indifference because survival cares not for emotion.

The simple answer would be Chicago will beat the hell out of you.

The main character in Ghosts is a very independent contractor for larger car-jacking jobs. She has a steel-resolve, and despite her illegal profession, she keeps a very straight, moral path that distinguishes her from pretty much everyone else she works with, or encounters. For her, it's all about survival. Until the end, where her solid disposition eclipses into madness, as if she got bitten by the evil she was railing against. So my question is kind of a philosophical one: are evil people insane, since it's not really accurate to call mentally ill people evil?

I think it really depends on the person. In the case of my protagonist, she wasn’t evil, but had to navigate a world of hell which ultimately consumed her soul. It was a slow and steady decline. Cracks in her solid disposition chipped away her armor. She knew what could become of her if she didn’t find a way out. Signs were all around her that time was not on her side but she was too caught up in the rat race to slow down enough and sort it all out. I’d argue she was going insane slowly just by being neutral in a world she really didn’t want to be in but had to navigate for survival. Her evilness was more or less the natural conclusion of her personal expectations of being a productive citizen living up to the social contract she felt she was cheated from. Sometimes with people like her the highway to evil is paved with saintly intentions and minor character flaws that come out under stress. It’s like people that go to war and come back shellshocked. Once the mind fractures, all types of suppressed demons come out. Some people handle the stress well, others, like her, tend to have a breaking point that leads to a point of no return. So I wouldn’t call mentally ill people evil, and I wouldn’t call evil people mentally ill.

Your skill for tight, long-volley dialogue is pristine. In elements of format, it's definitely the driving force in Ghosts. It's intense, uncompromising, yet also hilarious in moments – the quips are just as jabbing as the cruel moments. Do you find you hone this skill more on paper, or through your own environmental exchanges in real life?

As you well know I absolutely, positively LOVE satire and write it quite often, lol. However, I don’t think I honed those types of skills on paper. I think it was always there in the background. Probably a combination of years playing the dozens with my friends and family, listening to one too many Richard Pryor albums before I was old enough to buy them, and watching countless hours of sketch comedy growing up – mostly Benny Hill, In Living Color, old school Saturday Night Live, and The Carol Burnett Show. All of these were probably a subconscious study of comedy from the masters that knew how to bring a humorous element to tragedy.

Funny thing about my novel is I didn’t intentionally set out to put a comedic element into it. It’s just naturally present in my characters since they are Chicago characters. Anybody from Chicago, especially those hailing from the south and east side of the city, will tell you they are hardcore on the jokes and sarcasm. It can be comedically brutal sometimes, like telling jokes at The Apollo, just in regular informal conversation. And it cuts deep sometimes, even if it wasn’t said out of maliciousness. But it gives a little bit of air to a suffocating environment, which my characters definitely needed a lot of.

I've heard you mention your work has often been called "too black" or "not black enough." It's ignorant to reduce a literary work to a skin color on either side of that fence, but objectively, what do you see in your work that evokes such polarized reactions as those, or the downright hostile reactions in others who just can't handle it?

This isn’t an easy question that can be answered in a paragraph or two, because of the multifaceted factors that have contributed to the state of racial affairs in American publishing. The central thematic constant is modern black writers looking to be commercially viable have to engage in varying levels of tokenism to get their careers into the mainstream. All non-white work is judged through a racial lens – if it wasn’t you would be able to go to the book store and find White Caucasian Literature across the isle from Black African American Literature or Asian American Literature. All of this is from a lot of industry practices from back in the day that have carried over, primarily the thought that white people won’t buy black books if the characters don’t fit certain stereotypes. Everything is centered around fitting you into a box, with race being the deciding factor of expectation of what the commercial audience will accept. The best way I can articulate this is the poetry genre – Maya Angelou is considered a “safe” poet. When you look up black poets she’s in the top five featured alongside staples like Gwendolyn Brooks and Nikki Giovanni, all “safe” poets that really don’t bring a lot of political or social commentary into their works. Anything outside of that boundary is not promoted and silently blackballed. Gwendolyn Brooks went through that in her career, which is why people know "We Real Cool" and hardly anything else. This is the conditioning, because plenty of us know the staple writers while their contemporaries like Jamaica Kincaid, Carolyn M. Rodgers, bell hooks, and Audre Lorde are ignored because their works are harder, rougher, more political and less establishment.

As far as my own work, it’s just unapologetic, unladylike, lacks a lot of romance driven themes, and comes from a place that commercially is only heralded as a comfort zone for black male writers. If you look at top black writers from back in the day writing in a similar tone as mine, they are overwhelming male. We all know Donald Goines, Chester Himes, Iceberg Slim, and writers like that, but we don’t know any female contemporaries in the gritty hardcore crime genre. Toni Morrison, Octavia Butler, Alice Walker, and Maya Angelou were definitely not doing it. It wasn’t until the 1990s that you really started having an explosion of black female writers like Terry McMillian, Rosalyn McMillian, April Sinclair, Dr. Bertice Berry, Connie Briscoe, Tina McElroy Ansa, Bebe Moore Campbell, Gloria Malette and others, but all of their works are extensions of romance, mostly the bad side of it, but still in the genre. So yes, sexism has definitely played a major role in giving black women a commercial platform to write about something other than love in its many good and bad splendors.

You're extremely outspoken, specifically with the hypocrisy of political correctness. Do you think this kind of policing trend comes in waves with art? Do you think literature is inevitably going into a more sanitized direction, or do you feel part of a growing movement of authors effortlessly writing challenging work because they actually come from challenging environments?

I wouldn’t say I’m extremely outspoken, lol, I’d say not enough people speak out when the shade is at high noon. There’s a lot of things at the commercial level that trickle down to indies trying to keep up with the commercial joneses so to speak, and a lot of that definitely plays a part in this cancel culture censorship mentality plaguing the indie side of things we see and have experienced today. I’ve just felt on this side of the coin that by not saying anything I’m condoning the bad behavior of individuals and organizations targeting writers and publishers for expressing their art in a non-politically correct manner.

As far as the policing trend, that really hasn’t happened in American literature to this extent before. A lot of people have forgotten what the point of being an adult is and the joy of reading as an adult. D.L. Lawrence didn’t get slut shamed for Lady Chatterly’s Lover as hard as some people drag writers and publishers on social media trying to get them canceled for being “triggering.” In America though, I think it’s a natural consequence of people not reading as much as they did fifty years ago, combined with the rise and power of social media. And as we know absolute power absolutely corrupts.

American literature has been sanitized for quite some time – there is only one big box chain bookstore left in America, and that’s Barnes and Noble. They’re surviving solely being an over glorified campus bookstore more often than not. Smaller bookstores that have been a staple in a city near you are fewer and fewer every year. Used bookstores are disappearing. Amazon has conquered online and micromanaged everything down to sub-genre, giving preference to the big name authors. With more and more publishers forming and less and less diversifying places for them to sell their product, over-saturation is occurring on a massive scale. You can’t get more bleached out than that.

Yes, there is a growing movement, but it isn’t taking root like it properly should. I love seeing the indies fill the void and trying to steer publishing back to what it was in the 1970s with healthy competition and taking chances. But the reality is great indie publishers and writers in America don’t have good distribution without going through a conglomerate, so voices that should be given a wider audience won’t because the commercial side of things doesn’t want to lose the control they’ve spent decades amassing and taking over. Throw in the cancel culture police trying to censor certain genres and it’s a recipe of stagnation disaster for those indie publishers and writers trying to break out the box.

There are racial slurs all over Ghosts, on almost every page — you're even giving Ellroy a run for his money. Yet, it's clear they're intrinsic to the story, the characters – your use of racial epithets seem especially essential to the terrifying world you are leading us into. What is the difference between your work and someone who rattles that stuff off perhaps more irresponsibly? Where do you draw that line?

There are racial slurs all over Ghosts, on almost every page — you're even giving Ellroy a run for his money. Yet, it's clear they're intrinsic to the story, the characters – your use of racial epithets seem especially essential to the terrifying world you are leading us into. What is the difference between your work and someone who rattles that stuff off perhaps more irresponsibly? Where do you draw that line?

Honestly, there is no difference. People of all races say racial slurs all the time – this is life in America. Of course we know saying nigger stings the most and rings the loudest because of its connotation to Black American History and its societal double standards depending on the race of the person saying it. I’m sure some will give me a pass and some will question why I didn’t write “nigga” as opposed to its correct spelling when black characters say it, as if that somehow gives it a pass. And my reasonings for that were to dive into the underlying hatred, struggle, and oppression my characters live in, and how this has shaped their world view. That’s exactly what racial epithets to describe black people have done throughout the generations.

I don’t think you can use racial slurs irresponsibly if you’re being true to your characters. In the case of my novel, racial slurs create the construct of the America they live in. They aren’t politically correct and never will be because they don’t have the luxury. So it makes sense since they aren’t going to say Caucasian when they’ve said honkey their entire life referring to white people. They aren’t going to say Negro when their whole life has been saying Nigger in varying tenses as nouns and verbs.

Either way I don’t think we should judge those we feel are using such language as irresponsible. Whether or not we like what they say, defend their right to say it how they feel it needs to be said. If it’s too much for your sensibilities and taste, the option of putting it down and reading something else exists.

What was your research process like for Ghosts? For example, I know you're a, uh, vegetarian...

I wasn’t a vegetarian when I first wrote it, lol. I really didn’t do much research. The novel started as a short story I’d written of the same name. I’d sent it out to a few people and nobody would touch it, so I started tinkering with it and an entire book unfolded out of it. All I wanted to do was tell the story of this tradeswoman that did everything right to live the American Dream and it turned into an unorthodox gig economy nightmare. We see automation, elimination, and outsourcing of employment—if not total industries—in America regularly the last twenty years. My character represents one of millions lost in the struggle and left out to dry.

If one were to put it in a genre-fiction box, I would say Ghosts is 3/4 bleak crime-fiction, then for the last quarter, it takes a sharp left turn into what I feel is straight horror. Was there a conscious decision to cross genres here, or was it more essential to convey certain out-of-body feelings in the arc, because I saw a lot of the more over-the-top elements towards the end as symbolic more than literal?

Believe it or not, I don’t find my novel to be bleak crime fiction or horror. I’ve always maintained the belief it’s gritty political fiction with elements of crime, but I’m sure it won’t be listed as that. I definitely didn’t think the last quarter to be horror, more so it upped the crime stakes a little bit. Remember, women in books like this aren’t considered to be as vicious, hardened, and cold blooded as their male counterparts unless romance is involved in some way. My protagonist is definitely different in her motivations, so her sharp left turn in a different direction I think shows growth, albeit negative, trying to exist in a system that has taken the ability of her to legally take care of herself as an adult from her.

No, there wasn’t a conscious decision to cross genres since I still don’t think I did, lol. The challenge was staying true to my character and the different issues she faced and navigated through. Writing her downward spiral was terribly difficult as things of that nature are an intimate, personal thing that has no template or guidelines – details vary person to person. Some people will find her to be a villain, others will consider her a victim, and some might chalk it up to her career being in the wrong place at the wrong time. As you see from your interpretation, it’s in the eye of the beholder from their experience.

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.