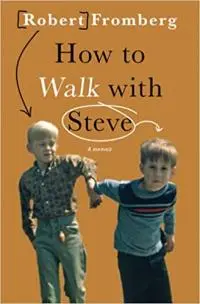

Photo via Rob Fromberg

By their very nature, memoirs can have the tendency to be self-indulgent, oversharing, name-dropping, sensationalistic and, yes, irresistible invitations into an exceptional person's charmed or cursed life. Yet, if a memoir falls into this kind of no-stone-unturned tell-all, something about the read remains surface-level, superficial, and predictable. With Rob Fromberg's new book, "How to Walk With Steve" (Latah Books), he totally reconsiders the format in hazy yet magnetic chiseled vignettes that chronicle Fromberg's life with his autistic brother Steve, under the shaky roof of matriarchal alcoholism. It's a tale of unique survival, that follows Fromberg moving out at an early age to cut his new-wave teeth at CBGB/Max's Kansas City, then eventually looping back to become Steve's legal guardian — at the risk of rattling Rob's own romantic pursuits. What's especially unique about the memoir is Fromberg's unlikely surrender to Steve's influence in his own writing, as he looks at the past with a detached, matter-of-fact innocence — something rare, considering we typically opt for the trials of life to merely harden us.

What would you say to the uninitiated cynic who might say, "Rob, you're not exactly a celebrity, so why should I care about your memoir?" When did you realize you had a story worth telling in such an idiosyncratic fashion?

I believe the more personal a thing is, the more universal it is, but to get to the personal, you have to forget about the universal. And by universal I mean how others will feel about it. I started this book not as a book, but as personal housecleaning. I knew that some elements of my life hit topics of broader interest—autism, alcoholism, the early days of CBGB—but to me, my materials were 60 years of uncomfortable, embarrassing moments lying around in messy piles in my head and body, and I was getting tired of living in such a mess. So I started recording them as closely as I could to how I actually experienced them. By documenting them in this way, I could re-experience them in a more controlled fashion. At a certain point, I saw the pieces taking shape into something that, mysteriously, hung together as a book, but I didn’t want to examine that too closely, didn’t want to invite the Censor or the Evaluator to intrude. Also, to some extent, I just wanted to get the damn thing over with; reliving all that was no fun. I wrote one draft and sent it to two publishers. Both expressed interest, which was nice confirmation that the work wasn’t wholly private (although the term “hard sell” did come up).

The way you portray alcoholism is unlike any way I've seen before. I think we're accustomed to see this story told with broken glass, vomit, rock bottom DTs/jail time, yet you paint it in a detached, almost unemotional way. You offer more subtle clues to the illness rather than some climactic, sensational scene, which to me, feels more accurate. You show how insidious the disease can be, how easy it is to make inner excuses for, as the child growing up with this kind of parent.

In all aspects of the book, I wanted to be fiercely true to what I experienced in the moment. When it came to having a parent who was an alcoholic and sleeping pill addict, my experience as a child was of small moments that didn’t quite add up. Later, when I was in my late teens, even when my mother was close to death, each experience was its own new and unknown piece of confusion that crowded out any broader context. In the book, I get to the more dramatic stuff like DTs, but that is so inherently intense, it certainly didn’t require any hyping from me. I just stuck with recording what I saw and sensed.

The book hinges on your autistic brother Steve, how you went from his sibling to his legal guardian; the responsibilities and therefore the bond, ever-unfolding. The inherited caregiving appears a handful, not what you signed up for as a kid, yet you're careful to paint the more innocent, almost whimsical parts of autism that might reveal someone's cynicism if they were to find fault with his behavior. I was really taken by that series "Love on the Spectrum," where I often found myself thinking, "Shit, these people with autism are more relatable to me than most people. They just don't want to deal with the confines of socially convoluted bullshit, keep things simple and rhythmic as possible."

Even when Steve was behaviorally uncontrollable as a kid, I found him to be a beautiful observer of the world. To me, that was his defining characteristic. The way he eyed bookshelves along their edges. Have you even tried that? It’s very dramatic. And of course his diagrammatic drawings of school buses, and his freehand street maps. Perhaps my parents being painters helped; I just loved watching his process of observation and documentation. As the years went on, I saw my own perceptions, and my writing habits, being shaped by Steve’s view of the world as I understood it, which created a real kinship. Of course, taking care of a kid who was only minimally verbal and otherwise a major handful was hard for me both before and after my parents died. But I was a taking-care-of-business kind of kid, so that left me plenty of room to enjoy Steve as a lifelong companion even as I worked on his activities of daily living.

I know it's more steeped in abnormal psychology than for personal speculation, but considering your proximity to your brother and the hands on experience, do you have any theories about why autism has become so prevalent, almost normalized; now that we've created more inclusive terms for those on the spectrum like neuro-diverse? I know at least five couples raising autistic children right now, whereas ten years ago that wasn't the case.

Steve was among the first wave of people diagnosed with autism—this was back in the mid-1960s. Autism was a mystery, barely known to the public and not particularly well understood by professionals. As far as our family knew, Steve was the only person with autism in our town of Peoria, Illinois. Yet, when my parents basically blackmailed the school district into starting a program for autistic kids, lo and behold, the classroom was full. Where did these kids come from? They were out there somewhere. As I grew, I met many people who, to me, had multiple characteristics of autism, but in a milder form than my brother, and were out there struggling to make their way in the world without any kind of diagnosis or support. I’m delighted that a broader spectrum of autism is being recognized. I only hope that the people with autism who don’t speak, who have serious behavioral challenges are not forgotten as we recognize this broader spectrum.

"How to Walk with Steve" is also 1st wave NYC punk rock adjacent since you cut your teeth living right around the corner from CBGB, and you were a regular at Max's Kansas City. I was relieved that you refrained from name-dropping like most punk/rock memoirs – no parasitic coat-tail riding. Instead, you actually describe these luminaries instead of telling us who they are. I knew exactly who you were talking about though, so it felt more inclusive like I was in on the secret rather than distracting the reader with some who's who we've all heard a million times.

"How to Walk with Steve" is also 1st wave NYC punk rock adjacent since you cut your teeth living right around the corner from CBGB, and you were a regular at Max's Kansas City. I was relieved that you refrained from name-dropping like most punk/rock memoirs – no parasitic coat-tail riding. Instead, you actually describe these luminaries instead of telling us who they are. I knew exactly who you were talking about though, so it felt more inclusive like I was in on the secret rather than distracting the reader with some who's who we've all heard a million times.

Ha! In the first draft of the memoir, after the New York City chapter, I broke point of view and said to the readers, “I think I let everyone down by not giving you enough names of punk luminaries, so here you are,” and I listed about 30 bands and people. I felt there was no point in recording anything anywhere in the book that wasn’t truly unique to me. I mean, sure, seeing Television, with Richard Hell still on bass, open for Patti Smith, who at the time still had no drummer, at CBGB when I was 15 changed my life, but that didn’t feel like anything specifically mine. On the other hand, talking with the pool players in the early evening before Television played did seem like mine—more private, more memorable.

What advice would you give to someone who wanted to turn their life inside out into a memoir? Did you feel the process was therapeutic or did it merely wake up the demons again?

Therapeutically, the process was 100% successful. All those pains and embarrassments got put into packages as cushioned and firm as what our Apple products arrive in. I suspect the only way to achieve that outcome, for me—and likely for others writing memoirs—was to fully occupy the moments being described. That required many pauses to check my impulse toward easy, attractive, self-serving descriptions, instead insisting that I find the nakedness of each moment, and to record that without adornment or hype. And it definitely required not thinking about publication.

I recognize that this perpetual-present form of memoir writing begs a question: What about the richness of perspective that distance brings, that allows a writer to imbue wisdom and significance and meaning into the events of one’s life? I respect memoirists who can do that. But I can’t. I’m not that interested in meaning. Any attempts at figuring things out in the book happen in the moment. Any other attempts to derive meaning seem inherently limiting to the materials. Let the jury decide on significance. All I can do is testify.

Get How To Walk With Steve at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.