Author photo courtesy of Kim Vodicka

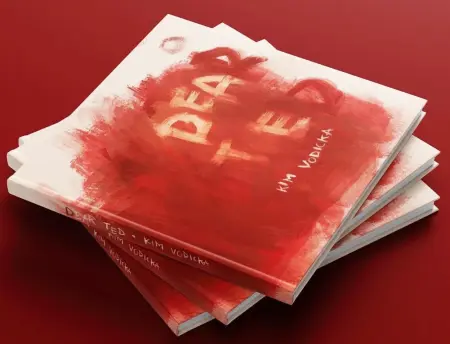

Memphis author Kim Vodicka is not just a writer—she's an energy, a feral vitality that challenges form and disfunction. Her new hybrid fiction/memoir prose-poem collection Dear Ted (Really Serious Literature) is a searing deconstruction of what she calls "the Ted Bundy of Love," a spirit that possesses men, feeds off women, and confirms the mutual death-drive. Beyond the page, Vodicka is a compelling performer; caustic as Lydia Lunch at her most confrontational, yet sarcastic and squirm-inducing like refined stand-up comedy. Call it feminism beyond rhetoric, empowerment without the pandering; where the abused becomes the abuser's worst nightmare. Above all, it is fucking art: blood for paint, like the cover portrays. Ready or not, Vodicka unleashes the same intimate napalm in this interview as she does in her written/spoken work, so fair warning: you've passed the point of no return.

While most of Dear Ted is violent and vengeful, there are occasional moments I felt were sort of romantic, like the line “I’ll wrap my cunt around your heart, labial skin graft becoming a new aorta, secured to your heart with pubic hairline sutures, the origin of your pulse pulsing the pulse of my clit.” There’s also a reoccurring theme of “intimacy addiction.” Why do some feel they can’t ever get close enough to someone? And why is it that you never really know someone until it’s too late—until they have their claws in you?

The book is personal—it’s an “autopsy” of a specific relationship, but alludes/pertains to several others. I struggle to feel close enough to the people I love because they’re often emotionally unavailable. I have a high threshold for pain, so I’m often in relationships in which my feelings are neglected. It’s a recipe for repeated involvement with people who are, in the best instances, inconsiderate, uncaring, and unkind; a person not fully present emotionally. Meanwhile, the person makes you feel like you’re not enough; belittlement, degradation, verbal and/or other abuse. Or, they do it indirectly, more subtle—while considering why the person isn’t emotionally available/present for you, your negative self-esteem might lead you to conclude you’re not enough. In other cases, they were self-absorbed, emotionally bankrupt adult children—garden variety assholes, not necessarily the Ted Bundy of Love. Paradoxically, I wanted to feel their love—wanting to feel loved by those who do not have the capacity—a crusade of trying to be loved by the loveless. My struggles with self-love instability, codependency, and anxious attachment— which, together, create something that might be called “intimacy addiction.”

It would appear the surest way to their hearts is to literally remove these organs from their bodies. They don’t have hearts, in the figurative, symbolic sense, so there’s this longing to make what they’re not expressing, and what they can’t express, literal and visceral, to feel the palpitations palpably, the heart beating in your hand, against your cunt, circulating love throughout your body, mind, soul, spirit—that deep intimacy and cathartic romantic fusion. So, maybe I’m trying to get my claws, or scalpels, into them. There’s this impulse to fix the thing impeding the emotional connection, perform surgery on it, but that’s not possible, and that impossibility means being left with romantic delusions/fantasies that may go to extremes to self-soothe, even as they cause real self-destruction in real-time.

I explore the idea of walking into your own romantic doom. I’ve been in at least one relationship where the thought of leaving had me afraid for my life, and another in which my life was directly threatened.This doesn’t right any wrongs, nor is it victim-blaming, but having a high pain threshold is potentially part of the problem. When a person crosses that threshold, it can be shocking—like maybe you never really knew them until that moment. I see my own propensity to get into bad relationships, and knowing what I’m getting into early on, as a form of self-mutilation. A certain amount of pain, in love, feels normal to me. Pain is my love language, in the sense that it’s difficult for me to feel completely loved unless a person is making me suffer. Having inconstant self-esteem makes me believe I deserve to be mistreated and/or harmed in love, so I frequently seek out relationships with people who fulfill this, therefore reinforcing these thought distortions. On some level, I want to hurt myself by getting into these relationships. I felt a need—urgency, really—to explore these things in the book. I wrote Dear Ted, in part, to try and understand my masochistic, self-destructive relationship to romantic relationships.

The book is concerned with actual serial murder and victims, and makes comparisons between serial murder and intimate partner violence that may or may not culminate in murder. It also explores how being in love with someone with monstrous tendencies can feel like being in love with someone like Ted Bundy. There are comparisons made between serial murder and serial romanticide, hence the prospect of a Ted Bundy of Love. Dear Ted is also concerned with slower deaths and more indirect murders—the death/murder of the heart and soul—during bad relationships that may or may not even be abusive. It also explores the idea of serially murdering yourself by continuing to get involved in these relationships because, at some point, love addiction is a death wish. At its most therapeutic, it’s repetition compulsion, an attempt to score a victory over pain by repeating painful experiences, but it’s also self-mutilation and a death drive. At the time of writing the book, my life quite literally depended on trying to understand these things.

In the piece “Courtesy Flush,” there’s the line “I watch Forensic Files/because bitches love Forensic Files/Also because I need to know/how my unreasonably good-looking husband/might kill me/and get away with it.” Why do you think True Crime has become such a notorious hit with today’s woman?

Demons need invitations, but they don’t always RSVP. I’d say women, or anyone on a broader scale, watch true crime because they want to see and understand how evil operates, so they can feel more alert and vigilant in their own lives, learning how to recognize human evil so they can safeguard themselves and loved ones. The cases presented often have conclusions—they frequently get solved, and the suspects get apprehended—so there’s a feeling of satisfaction, comfort, and closure in that, even when justice is…imperfect. It gives people a (mostly false) sense of control and security. It’s also just fun to play detective.

On a deeper level, I think people watch true crime because we have a desire to understand monsters and maybe, if possible, try to find ways to sympathize with them, especially monsters who don't look/seem like monsters on the surface. Ted Bundy didn’t look like one. His outward appearance was so aggressively normal, it caused cognitive dissonance and even outright disbelief among people who struggled to accept that this “charming, good-looking, promising” young man could do what he did. That can’t help but fascinate. Monsters who are “just like us” are arguably the scariest of all. It’s hard to fathom, so there’s an impulse to find the humanity, even as we acknowledge they're beyond sympathy and redemption. There's something monstrous about human nature itself, so on an unconscious level, watching true crime might be a move toward empathy, to get in touch with the evil at our primal center, or even consciously identify with it. There’s that woman who wrote “How to Murder Your Husband” then did, in fact, murder her husband. If you find yourself fascinated by her case, maybe you relate to it on some level. Maybe you’d never actually kill your husband, but maybe you can identify with the impulse, and maybe reading or watching a show about it with a glass of wine and getting to bed by 9PM feels like opening a pressure release valve. It’s a form of therapy.

Unspeakable crimes, at the “educational” remove of true crime, can also excite desire— even sexual desire isn't out of the ordinary here. Many serial killers have/had groupies and female fandoms. Female killers, though rarer and often far more “shocking,” also have fanboys and hosts of admirers. Watching true crime can excite in the same way watching a horror movie or a car crash excites. It can be delicious to live vicariously through a horrific thing. It’s a morbid voyeurism that may even manifest as kink/fetish. Excitation always has the potential to be a gateway to enticement and seduction. Why would you allow yourself to feel attracted to someone who committed such heinous crimes against humanity? It’s taboo, forbidden, and part of the perverse fun in watching these things. There's enough degrees of separation, distance, and detachment to remove you from the reality of an offender’s crimes against your own kind and make you feel safe in that fantasy, even though the person, in real life, might severely harm or kill you. It’s the society of the spectacle effect. It’s also the beauty of what I call the realm of pure fantasy. I think reading Dear Ted is like watching a horror movie, reading someone else’s diary, witnessing a car crash, jerking off to internet porn, going to primal scream therapy, and watching true crime.

Dear Ted is fiercely anatomical, with a sharp focus on the flesh that holds in our blood and guts until we find someone to let it all out. What’s your medical history? Ever study medicine? Why don’t most people know how their bodies work?

I didn’t understand how my body worked until I started having problems with it in my early 20s. Up until then, I lived almost completely in my head. The most significant part of my medical history was chronic digestive problems, which I spent over a decade trying to diagnose, manage, and cure; undergoing tests, scans, and procedures, even surgery, all to no effect. I finally saw a physical therapist who said my digestive system was fine, and correctly diagnosed me with pelvic floor dysfunction—likely caused by sexual trauma in my late teens/early 20s.

In my later 20s I became obsessed with my sexual anatomy to figure out my physical “formula” for having climactic sex, which I’d hardly had at all up to that point. Through trial and error and self-assertion, I figured out what I needed to have an orgasm with any person every time. I’m finding this connection between pleasure and discomfort interesting here—how feeling the opposite of comfort and pleasure were the things that led me to listen to my body, figure out how it works, and try to master it.

Listening to your body means having to confront inconvenient, uncomfortable, unpleasant, disgusting things you might prefer to ignore to your death, even if ignoring them might mean your death. It means taking note of how you feel, experimenting with adjustments, paying attention to patterns. Some people aren’t disciplined, brave, and/or honest with themselves enough to do that; they lack the strength to confront their own gross anatomy/humanity. We pretend we’re not animals, but an illness or injury can quickly put you face-to-face with your animality. Knowing how your body works means being able to physically feel, and interpret those feelings intellectually and intuitively. It requires diligence, fearlessness, and willingness to confront the truth.

When I read with you in L.A. last month, I was glad to witness you actually performing this work, engaging with the audience. Why do you think this is so rare these days? It seems most authors opt out of the spoken word performance element and see how little they can get away with, preferring to simply read from their books and bore the audience to numbness...

Or read off their phones, which drives me crazy. I realize it’s practical, but it shows a lack of preparedness and concern for how you and your work will come across. When I look at photos of a reading, and I see someone reading off their phone, all I see is someone looking at their phone. I don’t see art happening. In person, it’s a little more tolerable, because at least the work is in the air via the voice, but there’s already enough phone-gazing in everyday life. If I want to watch someone looking at their phone, I can walk down the street or go to the gas station. In the context of performance, it can be distracting and undermine the effect of what you’re trying to convey.

I don’t think writers must be performers, but my favorites are Cris Cheek, Nettie Zan Powers, Kelsey Marie Harris, to name a few contemporaries. I wish writers would put more work into performances of their works. A reading, when well-executed, gives the work energy and animates it. The performer becomes a lightning rod between the creative work/source and the audience. It’s an opportunity to reach out and grab people and connect. There’s an immediacy to performance—it’s the shortest distance between the art and the audience. Writers should hone that craft, use the opportunity to give life to the work to directly implant it into the minds and hearts of an audience.

As a feminist writer, what are your views on modern masculinity? I feel the term “toxic masculinity” hasn’t really helped anyone—now you can’t think of the term masculine without feeling the whole concept has been poisoned, even though the elemental definitive attributes to masculinity are wholly positive. For example, it’s a masculine trait to confront disrespect. Do you think masculinity could ever be an asset to feminism?

Even at their “essence,” I wouldn't say masculine attributes are wholly positive. Certain masculine attributes—dominance, aggression, competitiveness, lack of emotion—have gotten humanity into the mess we’re in today. I see “toxic masculinity” as redundant because, if it’s not a matter of poisoning somewhere down the line, there might be something wrong with masculinity at its core. Women are already forced to adopt certain masculine attributes to advance in society, whether that means getting a higher-paying job or running for office, but what’s opposite is not equal. The preponderance of men in charge still control our bodies and manipulate our attributes to their benefit. It has nothing to do with principles or ethics or spiritual beliefs. It’s about control, repression, and maximizing consumption.

It might be a masculine trait to confront disrespect, but would it be necessary to confront disrespect if men had not basically…invented disrespect? “Everything you think you hate about women wouldn’t exist without shitty men!” as I wrote in my last book, The Elvis Machine. The recent movie Men explores some of these things brilliantly—masculine and feminine attributes and “essences,” and how there's something amiss with the nature of masculinity—a mutation in the gender that conquers the feminine and co-opts our bodies/attributes to give birth, and keep giving birth, to generations of an increasingly perverse, horrifying, and destructive version of itself. Women, to our detriment, will make every effort toward gentleness, understanding, and empathy until we are forced to adopt the masculine attributes necessary to protect and defend ourselves. In that respect, masculinity is an asset to feminism, but it's also to blame for creating a mutant humanity and perverse society in which adopting masculine traits is part of the criteria for simply being able to exist in peace, not to mention having any chance of upward mobility and success independent of a husband or male protector.

My favorite aspect of Dear Ted is how confrontational it is, yet fiercely conflicted. It’s one of the most honest things I’ve read this year. Why do you think some women are attracted to dangerous men?

Again, my attraction to dangerous men comes from a repetitive-compulsive death drive and propensity for self-mutilation. I was date raped in my late teens and later wound up dating my rapist, who went on to physically abuse me for about a year. Having low/no self-esteem, being codependent, and/or anxiously attaching can make a person more likely to become attracted to human monsters like these. Over time, being attracted to dangerous men feels normal. You get acclimated to it, build up a high pain threshold, continuously invite these people into your life.

I’m really only a “horror writer” because my life is such a nightmare. “Horror reinforces attraction and excites desire,” as Susan Sontag says. Feeling scared creates this giddy excitation, and if you’re scared of a person to whom you’re also sexually attracted, it can be an intensely erotic experience. I don’t necessarily think this is a sign of pathology or even unhealthy, but maybe I’m not the best person to ask.

Attraction to monsters also has roots in empathy which is largely a female attribute. Believing a violent criminal has been wrongfully accused could make them appear a victim of society, so you're more inclined to fall in love with them. Carol Ann Boone fell in love with Ted Bundy, and staunchly defended his innocence after he was put on Death Row. Belief in a dangerous person’s innocence can be the impetus for the attraction and fuel an entire deluded love fantasy.

This is all explored in Dear Ted. The book is quite personal, even autobiographical in places, but it deals in the universal as well; how a famous serial murderer and his killing spree is seen within the victim’s perspective. My intent was not to disrespect but to explore and understand. If I didn’t think these things were potentially helpful to others, I would have just kept the book as a diary under my bed.

Get Dear Ted at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.